The Cave

Part 2

Calvin Luther Martin, PhD

November 3, 2024

This is how I imagine Jacinto to have looked. Cather writes that Jacinto was a young man from the Pecos Pueblo.

With thanks to Lotus

Prof. Iegor Reznikoff

(See his biography, below.)

‟The location for a rock painting was chosen to a large extent because of its sound value.”

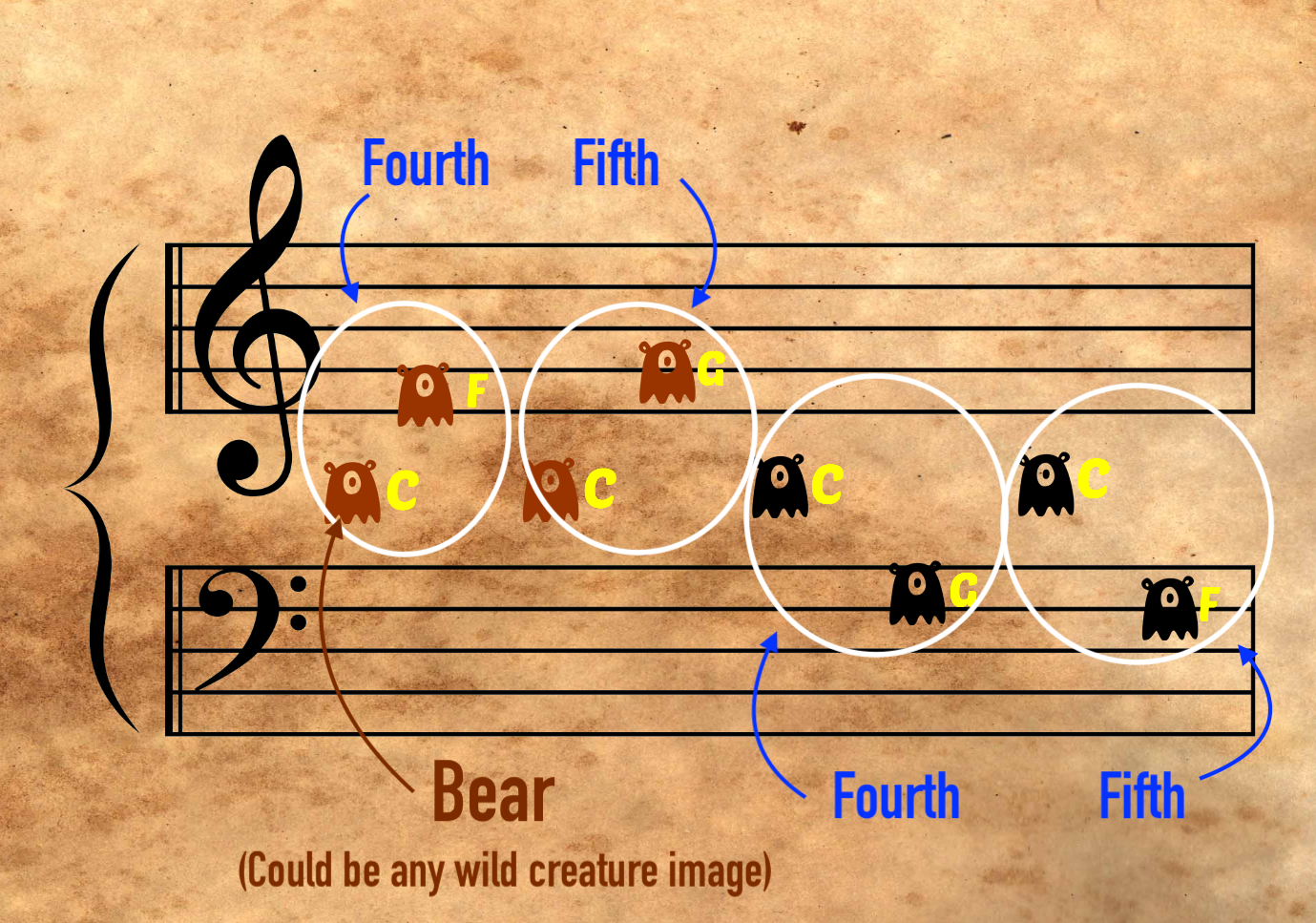

Before opening the “pop-out,” below, click here to listen to the so-called perfect fourth and perfect fifth tones in music. The first set goes up in the treble clef from C to F (fourth) and then to G (fifth). The second set goes down in the bass clef from C to G (fourth) and then to F (fifth).

Imagine that the mottled brown background to this musical staff is a cave wall. Now imagine hearing these "fourths" and "fifths" in response to a voice that begins humming or singing with a middle C tone. (I believe this is what Prof. Reznikoff is describing as a resonance or harmonic — especially with the fifth.)

Charles Baudelaire

(With thanks to Philip Dietrich)

On close inspection one can´t escape noticing a common pattern with all these sites: a constellation of identical forces (hydrological, geological, meteorological, zoological) triggering a stunning flowering of the human intellect. (With thanks to Gabriela for the above image.)

Caves are massive wind instruments loaded with infrasound, it turns out. What’s more, we now know that caves have a unique voice made up in part from extremely low level infrasound, down to 10-2 and even 10-3 Hz in discrete harmonics (resonances).[1] Each cave has its own ‟intrinsic harmonics and `timbre´ that depend on the cave morphology” — harmonics, timbre, and resonances yielding a characteristic infrasonic fingerprint, signature, or what Badino called ‟voice.”[2] ‟With a suitable device, it is possible to convert the inaudible `breath´ of the cave into a sound, a kind of speech of the cave itself.”[3]

It can be theoretically shown that the shape of each single conduit has effects everywhere inside the cave; therefore the air movement in each contains information about the whole cave.[4]

Not being a speleologist, yet evidently familiar with caves, Cather had her bishop refer to this phenomenon as a ‟dizzy noise,” ‟an extraordinary vibration” that ‟hummed like a hive of bees.”

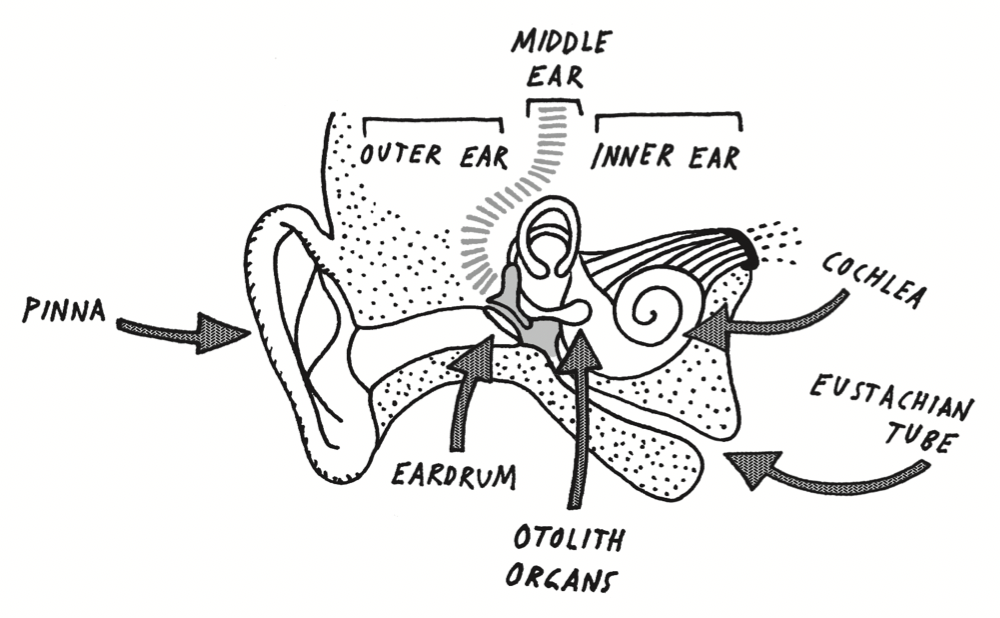

The vestibular organs (saccule and utricle in particular) are highly sensitive to infrasound. The literature on the subject is well-established. It is also well established that air pressure pulsations at infrasonic frequencies can dys-regulate the vestibular organs, causing vertigo, as Cather notes for Bishop Latour.[5] We will come back to the phenomena of vestibular stimulation.

The French archaeologist, Michel Dauvois, one of the founders of archaeo-acoustics, explains that ‟´it is the particular natural morphology of the cave that provides the resonance.´”[6]

Elementary acoustical models can describe the origin of infrasound harmonics; however, cave morphology is usually very complex, and the harmonic spectra of its `voices´ are extremely complex.[7]

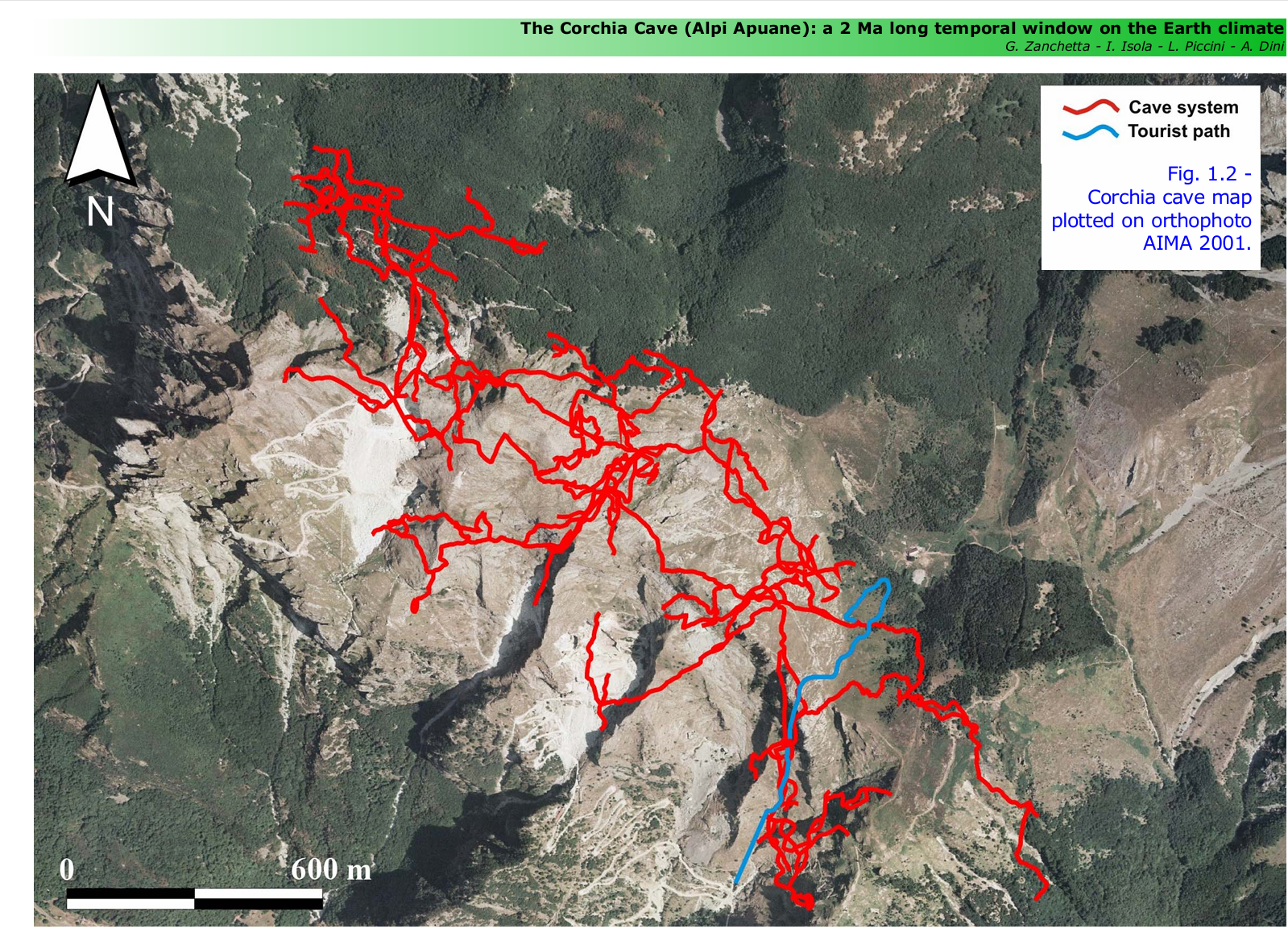

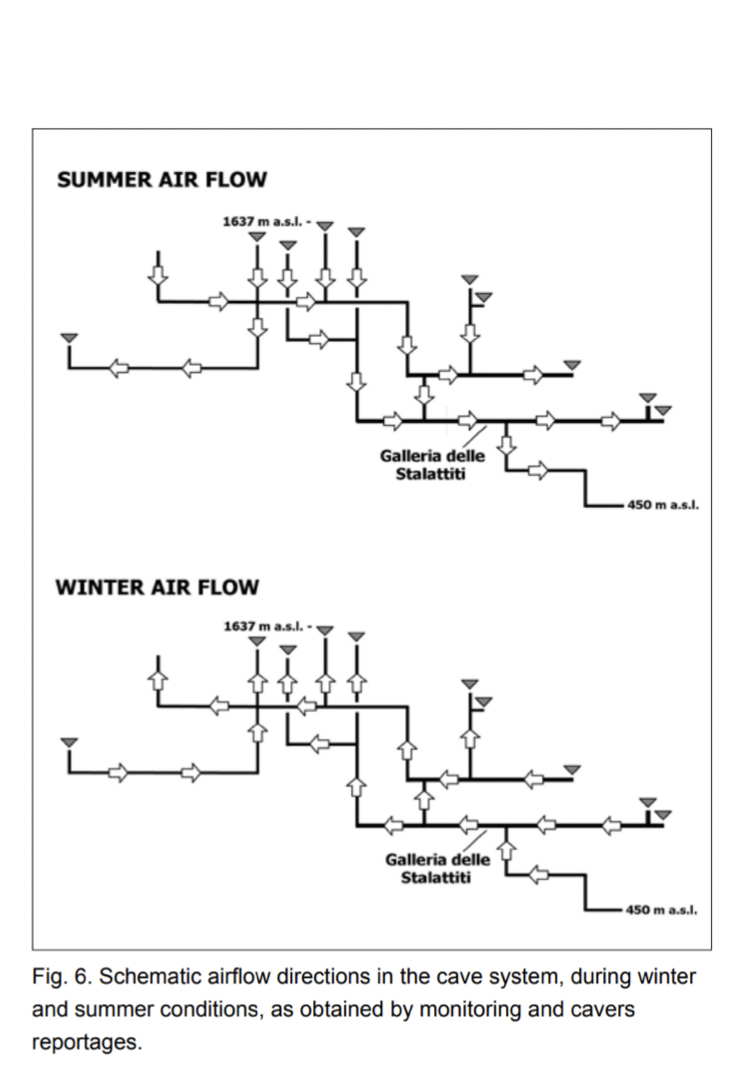

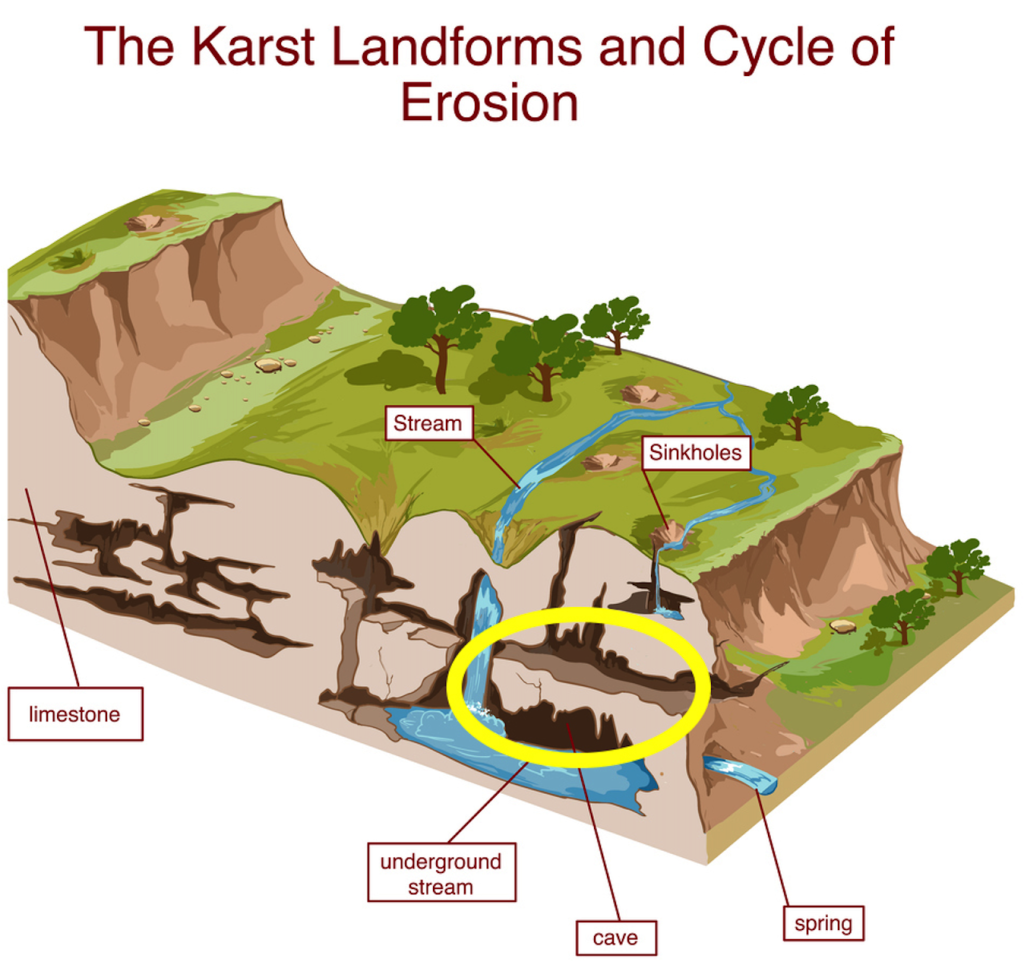

‟Low frequencies seem to characterize the whole system, whereas `high´ frequencies are emitted only `locally,´ i.e., by surrounding conduits.”[8] As an example, Prof. Badino describes the massive karst cave system of Mt. Corchia (Tuscany, Italy) as having a ‟common low frequency” of 0.000295 Hz which ‟corresponds to a period of 3400 s [seconds]. It would represent the note emitted by a 280 km tube, closed at one side.” He suggests calling this the deep or fundamental harmonic of the Mt. Corchia cave system.[9]

All complex caves have a unique deep or fundamental harmonic. ‟From the infra-acoustic [infrasonic] point of view, complex caves can be considered as systems of many different damped and coupled oscillators, and this could possibly be considered the origin of the [commonly found] pink noise.”[10] (Pink noise being an acoustic term for a type of sound humans hear as soothing and natural, sometimes compared to the sound of a waterfall.)

In his pioneering research on ‟Infrasonic Resonances in Natural Underground Cavities” (1969), William T. Plummer writes, ‟Since surface winds are rich in excitation energy” in the spectral range 0.001 to 1.0 Hz, ‟subsonic oscillations should be common in natural caverns. Such oscillations are experienced as alternating winds and may be observed very sensitively by watching the motion of a candle flame or smoke.” ‟Many … examples of fluctuating cavern winds have been found . . . , some in caverns that can be treated as simple Helmholtz resonators with necks.” [11]

These experiments show that low-order acoustic resonances may be detected in large caverns under both natural and artificial [such as human voice or clapping] means of excitation, in frequency ranges so low that the oscillations are experienced as slowly reversing winds.[12]

To which Plummer adds the intriguing observation, ‟In some cases, such acoustic observations can provide useful new information about inaccessible cavern structure.”[13] It’s conjectured that Pleistocene humans may have been able to navigate labyrinthine karst caves by a kind of echo-location or sonar, following the contours of corridors, galleries, and chambers by acoustic signals.[14]

Cather´s bishop describes, as well, a phenomenon like the ‟heavy roll of distant drums.” Latour asks his guide if he too hears it.

The slim Indian boy smiled. He took up a faggot for a torch and beckoned the Padre to follow him along a tunnel which ran back into the mountain, where the roof grew much lower.… There Jacinto knelt down over a fissure in the stone floor, like a crack in china, … plastered up with clay. Digging some of this out with his hunting knife, he put his ear on the opening, listened a few seconds, and motioned the Bishop to do likewise.

Father Latour lay with his ear to this crack for a long while, despite the cold that arose from it. He told himself he was listening to one of the oldest voices of the earth. What he heard was the sound of a great underground river flowing through a resounding cavern. The water was far, far below.… A flood moving in utter blackness under ribs of antediluvian rock.

It was not a rushing noise, but the sound of a great flood moving with majesty and power.[15]

“It´s terrible,” remarks the Bishop.

Awakening in the night, the campfire embers glowing, Latour witnesses his guide “standing on some invisible foothold, his arms outstretched against the rock, his body flattened against it,” listening to the great underground river through a portal in the cavern wall. “Listening with supersensual ear, it seemed, … supported against the rock by the intensity of his solicitude.”[16]

Latour and his guide had accessed what is technically referred to as a gallery — a ‟distinct path for the passage of [an] ancient river.”[17] It was this terrible and majestic force they heard through the ‟fissure in the stone floor.”

Caves are vast, complex conduits for two ‟flowing fluids”: water and air. ‟The phenomenology of the two … is completely different,” writes Prof. Badino. Air moves freely. Water does not. ‟Water can only flow downward and on the lowest part of conduits. Due to its enormous thermal capacity,” adds Badino, ‟water generally has the leading role in establishing the underground temperature.”[18]

Less dramatic than the rumbling rivers in deep-down galleries are the ‟condensation-evaporation processes which cover walls with thin films of water and create internal clouds.”[19] The condensation results from the coalescing ‟of two saturated air particles at different temperatures. The resulting `mixing clouds´ are so common underground to the point that cavers do not observe them.”[20] The clouds move with ‟air fluxes, with their imperceptible but continuous changes of speed.”[21] Besides being ‟cloud factories” (Thoreau),[22] the films of water have a morphological role, creating ‟insoluble inclusions which outcrop from the limestone.”[23]

It is this moist film that defines the dynamic nature of the cave. ‟For a caver,” explains Badino, ‟a cave is usually perceived as `active´ when a water film covers the walls.”[24]

I find Prof. Badino´s research especially compelling. Few individuals can match his resumé and few have been so tuned to reading and listening to the voice of caves — a voice wet with water. The man was a lifelong explorer and scientist, passionate about the ‟underground world,” reads his obituary in the International Journal of Speleology.[25] For over 40 years he researched scores of caves worldwide, including glacial karst caves in Antarctica and the Naica crystal caves in Mexico.

With Badino´s use of the term ‟active” in mind, consider this passage from Cháálatsoh´s narrative:

The place was so large that it extended as far as one could see, they say. At the entrance, whiteshell was prancing about, they say, whiteshell in the likeness of a horse.… All of different kinds, whiteshell horses extended off in great numbers, they say. A great amount of mist-like rain falling on them continuously, … they say.[26]

The repeated reference to clouds of mist is a subtle nod to sisna-te-l´s ‟active” state. And yet there is more to this active state than moist walls, clouds, and resonance, as Changing Woman reveals to her son. Namely, she instructs her son to engage the beings who were actively keepers of Equus — keepers no different from the Dark Ones who were custodians of the game at Chauvet, Hohle Fels, Geissenklösterle et al. These keepers have maintained an unbroken chain of custodianship from Pleistocene to modern times, as one might infer from Charlie Kilangak´s quietly-spoken observation, ‟Bears got ears on the tundra.”[27]

Changing Woman´s instructions suggest an additional dimension to the “active” state of Pleistocene caves: a cognitive state. The message of archaeology is exactly this: for 30,000 years,[28] Chauvet, Hohle Fels, Geissenklösterle et al. were cognitively ‟active” for humans. Navajo mythology (Changing Woman´s instructions to Turquoise Boy) confirms this cognitive, cultural, conceptual, perceptual, experiential, and perhaps linguistic active state. (Cather touches on some of this cognitive activity.) The bridge from an ‟active” physical environment to a cognitively ‟active” environment for Homo may have been the Dark One (witness the Bulky One in Navajo mythology) who, it´s clear, inhabited these caves for months at a time.

Stand back and notice a synchronicity emerging. A synchronicity composed of the aqueous qualities of ‟active” karst caves, cave resonances and reverberations (Badino´s ‟voices”), the signatures of fundamental cave harmonics, the presence of the Dark One, and the greatest spectacle of all: the voluminous outpouring of Pleistocene cave parietal motifs — which, by the way it is best not to call ‟art.” To call it ‟art” is as misleading as calling the Dark One a bear.

A human-cognitively active cave was a hydrologically, acoustically, and zoologically active cave. Consider this axiomatic.

I will get to the zoological part shortly. Right now we need to address what goes by the lame term, ‟acoustics.” Specifically, Pleistocene cave acoustics.

Archaeologists had long suspected a link between Pleistocene parietal motifs and the resonances and reverberations described above — resonances and reverberations that manifest themselves, as Plummer stated above, ‟under both natural and artificial means of excitation” — where artificial methods would include the human voice and other human-generated sound.[29] The long suspected link was confirmed by Iégor Reznikoff and Michel Dauvois.

In a remarkable article published in 2002, titled ‟Prehistoric Paintings, Sound, and Rocks,” Reznikoff summarized the evidence as a series of principles:

Principle 1: Most pictures are located in, or in immediate proximity to, resonant places. . . . Principle 1 is verified if we include among resonant locations those with sounding [limestone] draperies or stalactites.

Principle 2: Most ideal resonance places are locations for pictures (there is a picture in the nearest suitable place). Among the ideal resonant places, the best are always decorated, or at least marked.

These principles give a general outline of the relationship between the location of the drawings and the resonant places. It is also possible to formulate the following hypothesis, of which we found many examples:

Principle 3: Certain signs are explicable only in relation to sound.

Moreover, certain points have quite exceptional acoustics and produce the most extraordinary phenomena with vocal emissions. [See the Camarin effect, below.]

Since these principles are verified with a high percentage [of instances], it is possible to say that, in the caves we studied, the choice of locations for paintings was made mostly for the sound-value of these locations. Paleolithic people chose good resonant places; this is the meaning of the first principle: a picture requires sound; whereas the second principle, which concerns the extent to which resonant places were used, indicates the importance of sound in itself: sound calls for a picture.

To illustrate the last two principles, it should be noted that signs were (re)discovered aurally by advancing in total darkness through the cave and presuming that a sign would be found in a particularly resonant place, locating the latter, then switching on a light, and indeed finding such a sign, even in a place unsuited for paintings. This was done first in Le Portel [Ariège, France], in the Horse gallery. . . . Even more, some pictures or signs have been discovered (for the first time) by using sounds. In Le Portel, after my discovery of some locations interesting for their sound value . . . , Dauvois discovered some new paintings in these locations. More recently I have discovered … two red dots in a sounding niche (with a Camarin effect that lasts for 4 seconds) related also to sounding stalactites in a part of the . . . cave where no signs or pictures have been discovered before. This has been the case also with painted rocks in the open air.[30]

The Camarin effect derives from a niche of the Breuil gallery in Le Portel where a ‟single expiration [breath] or a simple sound vibration, mm, quickly brings you to stand within the resonance of the recess — it seems inconceivable that the painter would not have noticed it — and it produces low sounds that resemble a growl or the lowing of a bison, resounding down the whole gallery.”[31]

In the majority of sites he studied, repeats Reznikoff, ‟the location for a rock painting was chosen to a large extent because of its sound value.”[32] From this he develops a plausible linkage between the hydrologically, geologically, and meteorologically-derived ‟sound values” of cave walls and the voices of the humans who composed the motifs at these acoustically rich locations.

This acoustical quality [of the walls] must have been discovered mostly vocally since, for example, the tapping of feet is too dull a sound to make the galleries vibrate; moreover, since resonance is variable, a drum (which has a fixed pitch) would not suffice to determine so well the points of resonance (but could still serve as a support), whereas flutes and whistles are too shrill to cause the rock walls to resound — but of course they could be used otherwise in sounding spaces. Likewise, because of the relatively low frequency resonance it would have been men’s voices that were used and would guide the other participants (this in no way excludes the possible participation of women).[33]

From this he concludes that people ‟sang (in the broadest sense of the word) and listened for the eventual response of the cave, which was doubtless considered alive in terms of sound. (In total darkness, with only a few torches, this effect must have been striking and still is today; it is indeed very impressive to hear the cave reply from its very depths to an animal on the rock wall.)” Click here to watch a mind-blowing video of Prof. Reznikoff demonstrating this in the Arcy Cave (Burgundy, France).

Voices used consonant [as distinct from dissonant] intervals (unison, octaves, fourths and fifths), which is not surprising, since these intervals have been used universally and are strongly favoured by resonance (octave and fifth are clearly heard as harmonics). . . . The fifth is so apparent [in the caves he studied], sometimes with a little delay, that one is invited indeed to imitate it.

As far as the use of instruments is concerned, the low resonance would tend to suggest the use of the drum and the rhombus; but the musical bow, as both an excellent support to the voice and giving the possibility of varying pitch, would seem to be most likely. This reminds us of the famous horned sorcerer at Trois Frères cave (Ariège) where what seems to be a musical bow is represented. In specially sounding locations, flutes or other instruments could be used, as in Salon Noir or Isturitz (where flutes were actually found). This suggests also that real ritual concerts could have been performed, using voices, instruments, stalactites, . . .[34]

These resonances and reverberations have been voluminously documented, as well, from outdoor, open-air boulders and sheer rock faces — as in New Mexico[35] — confirming the same uncanny connection of ‟art” to lithically-influenced ‟sound.” Evidently our Paleolithic ancestors were masters at transforming rock faces simultaneously into a musical instrument and painter´s canvas — a ‟correspondence” captured by the 19th-century French poet Charles Baudelaire in a poem by the same name:

Comme de longs échos qui de loin se confondent

Dans une ténébreuse et profonde unité,

Vaste comme la nuit et comme la clarté,

Les parfums, les couleurs et les sons se répondent.

Like those deep echoes that meet from afar

In a dark and profound harmony,

As vast as night and clarity,

Scents, colors, tones answer each other.[36]

Baudelaire doubtless had a more proximal inspiration in mind when he wrote these lines, although this doesn´t concern me at the moment. His immediate purpose begs the question: What deep, hidden memory unveils itself, like an epiphany, when a Baudelaire, Monet, Bach, or Rodin reveals something this synchronous and harmonious? Is it a memory or a timeless participation? (Is there fundamentally a difference, one wonders?) And what is it that suddenly, forcefully awakens the reader, listener, or spectator, sometimes bringing us to our knees, in the exfoliation of Events (yes, capitalized) like Beaudelaire´s ‟Correspondences”?

Not knowing what to call these Events, we call them ‟art,” in conformity to the desiccated research of academia and soulless flatness of popular culture.

It´s not art. It´s the amassing harmony. Aldous Huxley nails it in the novel, ‟Island”: it´s ‟perpetual creation out of no-what-nowhere into something-somewhere.”[37] It is the Event from which we have been estranged for tens of thousands of years.

Somewhere within this dark and profound harmony, vast as night and clarity, where scents, colors, tones answer each other, we find the thing we call language.

Let me be clear. I am not suggesting human language originated in Pleistocene karst caves. The likelihood of this is approximately nil, especially considering the rich archaeological record of earlier hominins, as with African Australopithecines, frequenting karst caves as early as 2.5 million years ago.[38] What I am suggesting is that Chauvet, Hohle Fels, Geissenklösterle and the dozens of other nodes, where Ice Age man and woman left evidence of their presence over a 30,000-year span, are a benchmark, perhaps a decisive one, in human cognition and thus, speech.

On close inspection one can´t escape noticing a common pattern with all these sites: a constellation of identical forces (hydrological, geological, meteorological, zoological) triggering a stunning flowering of the human intellect. (I am uncomfortable with the term ‟triggering,” since it smacks of positivism.) The contextual features I enumerated (hydrology, geology, meteorology, zoology), taken singly or collectively, don´t tell the whole story. There is another dimension to all this; there is an invisible manifold, for want of a better word, performing within ‟the biggest natural wind instruments on earth.” A manifold that encompasses music, painting, sculpture, and undoubtedly human language. All of it, mind you, ‟In the Bear´s House,” borrowing the title of one of N. Scott Momaday´s last books.[39]

There is a synergy going on. Whatever it was — whatever explains the mind that came alive, as never before, in the caves of the Aurignacian and Gravettian — calls for the insights of a Rilke, Monet, Cezanne, Bach, Beethoven, Rodin, or a Reznikoff — a person of ‟the house of being”[40]

We encounter such an individual, a kindred spirit to Iégor Reznikoff, in the pages of the Popol Vuh, where an ancient Mayan with no name reveals the mind born in the karst caves of the Yucatán and Belize. Rilke could not have put it better:

K’a katz’ininoq, Now it still ripples,

k’a kachamamoq, now it still murmurs,

katz’inonik, ripples,

k’a kasilanik, it still sighs,

k’a kalolinik, it still hums,

katolona puch. and it is empty.[41]

“For ears attuned to patterns that run below the level of syntax,” writes Tedlock, the above text “seems to be one of the most densely poetic passages in the Popol Vuh,” the sacred text of the K’iche’ Maya of highland Guatemala. (The ancient lords of K’iche’ called it a “seeing instrument,”[42] since it allowed them to see through space and time—into the future and into the past.)

“For Quiché ears it is . . . the sound of chaos—not the maelstrom of Old World mythology, but a chaos of vibrations and pulsations.”[43] The language is ‟dense with alliteration and assonance, both inside its words and between them, . . . open[ing] language toward the direct imitation of what is outside it, evoking the sounds of a primordial world that consists only of a flat sea and an empty sky.”[44]

I must correct Prof. Tedlock. This is not a language of imitation, direct or otherwise; it is a language of presence and participation. There is nothing outside it — not a whiff of Descartes´s res cogitans and res extensa.

Nor is it meant to evoke the acoustics of a sterile sea and heavenly void. It is the voice of mankind, most likely singing,a blending with the resonances and harmonics of a cave: the bear’s house.

__________

Footnotes

[1] Badino, ‟Underground Meteorology,” p. 446.

[2] Badino, ‟Underground Meteorology,” p. 445.

[3] Cigna and Forti, ‟Giovanni Badino,” p. 459.

[4] Badino, ‟Underground Meteorology,” p. 445

[5] See Pierpont, Wind Turbine Syndrome (2009).

[6] Fazenda, ‟Cave Acoustics,” p. 1333.

[7] Badino, ‟Underground Meteorology,” p. 445.

[8] Badino, ‟Underground Meteorology,” p. 446.

[9] Badino, ‟Underground Meteorology,” p. 446.

[10] Badino, ‟Underground Meteorology,” p. 446.

[11] Plummer, ‟Infrasonic Resonances,” p. 1074

[12] Plummer, ‟Infrasonic Resonances,” p. 1080.

[13] Plummer, ‟Infrasonic Resonances,” p. 1080.

[14] Reznikoff, ‟Prehistoric Paintings,” p. 42.

[15] Cather, Death, p. 90.

[16] Cather, Death, p. 91.

[17] Valentin et al., ‟Speleoacoustics,” p. 70.

[18] Badino, ‟Underground Meteorology,” p. 447.

[19] Badino, `Underground Meteorology,” p. 447.

[20] Badino, ‟Underground Meteorology,” pp. 442-443.

[21] Badino, ‟Underground Meteorology,” p. 447.

[22] Thoreau, Maine Woods, p. 85.

[23] Badino, ‟Underground Meteorology,” p. 441.

[24] Badino, ‟Underground Meteorology,” p. 441.

[25] Cigna and Forti, ‟Giovanni Badino,” p. 459.

[26] Sapir, Navaho Texts, p. 121.

[27] See Lecture #x.

[28] Fazenda, ‟Cave Acoustics,” p. 6.

[29] Plummer, ‟Infrasonic Resonances,” p. 1080.

[30] Reznikoff, ‟Prehistoric Paintings,” pp. 43-44.

[31] Reznikoff, ‟Prehistoric Paintings,” p. 44.

[32] Reznikoff, ‟Prehistoric Paintings,” p. 49.

[33] Reznikoff, ‟Prehistoric Paintings,” p. 49.

[34] Reznikoff, ‟Prehistoric Paintings,” p. 49.

[35] See Waller, ‟Conservation of Rock Art Acoustics,” Rock Art Papers: San Diego Museum Papers, ed. Ken Hedges, 2003, vol. 41, pp. 31- 38; Waller, ‟ Rock Art Acoustics in the Past, Present and Future,” IRAC Proceedings, 2002, vol. 2, pp. 11-20.

[36] Geoffrey Wagner, Selected Poems of Charles Beaudelaire (NY: Grove Press, 1974).

[37] Huxley, Island, p. 333.

[38] See Clarke et al., ‟The Earliest South African Hominids,” Annual Review of Anthropology (October 2021), vol. 50, pp. 126-143; Clarke, ‟Latest information on Sterkfontein´s Australopithecus skeleton and a new look at Australopithecus,” South African Journal of Science, November/December 2008, vol. 104, pp. 443-449.

[39] Momaday, In the Bear´s House (NY: St. Martin´s Griffin, 1999).

[40] Rilke, Cezanne, p. xxi.

[41] Tedlock, Popol Vuh: The Mayan Book of the Dawn of Life, rev. ed. (NY: Simon & Shuster, 1985), p. 204.

[42] Tedlock, Popol Vuh, p. 21.

[43] Tedlock, Popol Vuh, 204.

[44] Tedlock, Popol Vuh, 204.

- Reznikoff, “On Primitive Elements of Musical Meaning.”[↩]