Confessions of a

Fugitive

Calvin Luther Martin, PhD

October 27, 2024

With thanks to Stanislav Kondrashov

Wallace Stevens

Rainer Maria Rilke

Wallace Stevens as Harvard student

Rilke

Click on the image, above. Turn up your speakers.

“Just a bad wizard”

Loon mask

(Bryon Amos, Nunivak Is.)

Hugo von Hofmannsthal

Ezra Pound

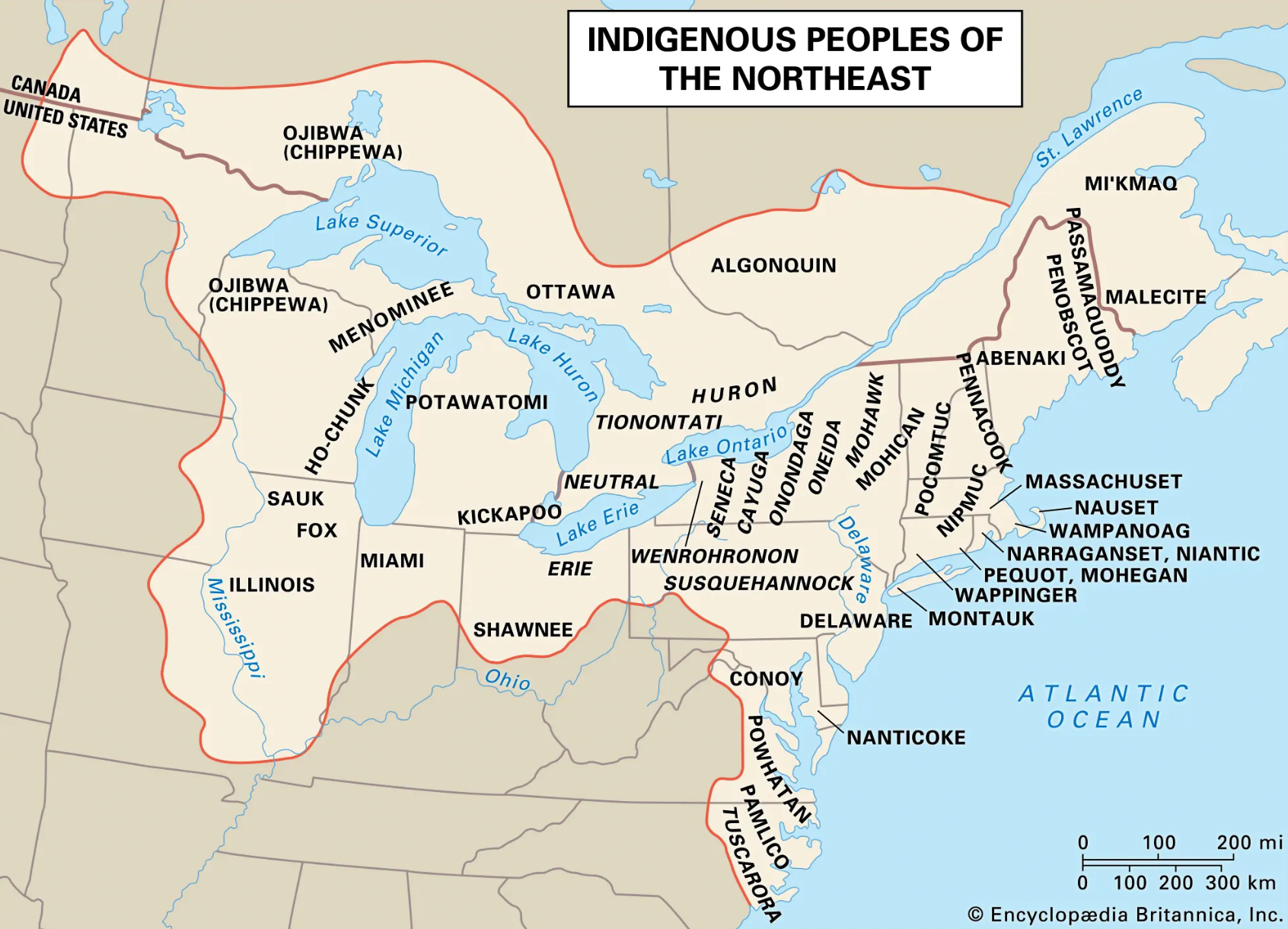

Leon Shenandoah, Tadadaho of the League of the Iroquois (1969-1996)

The most notorious cannibal of them all

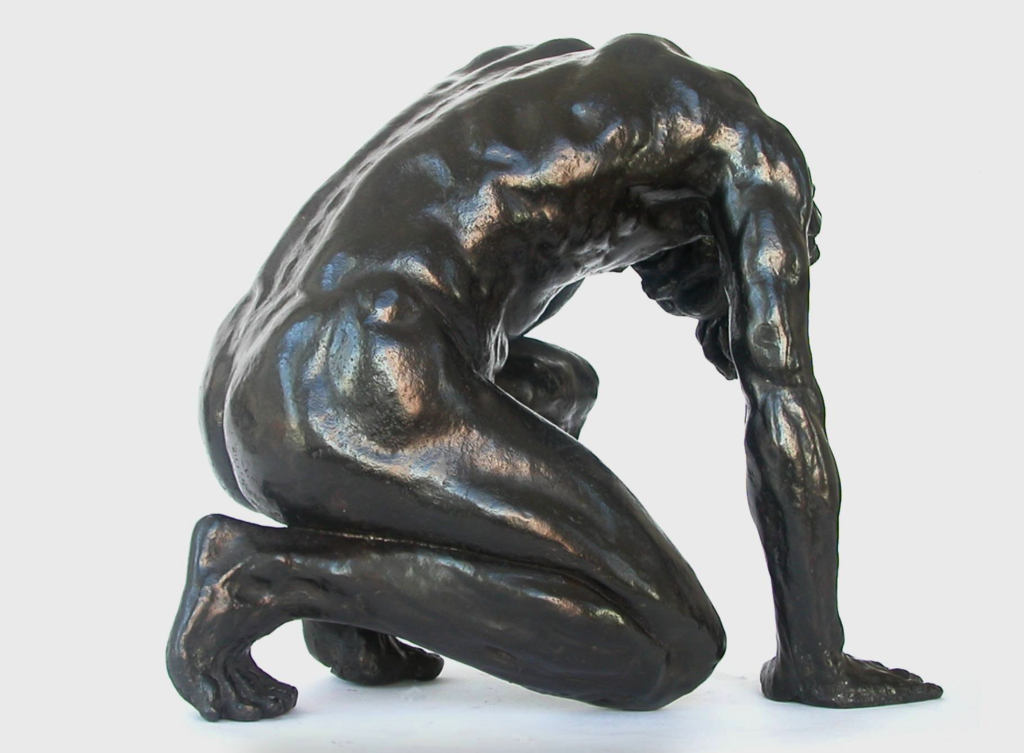

He was a formidable leader, the stories go, until he lost his grip on language. No one remembers how. He had once been a man of wisdom and gravitas, but words meant nothing to him anymore. They say his mind snapped, that he became a madman in this very wilderness, where he preyed on unsuspecting travelers and ate them.[1]

This is the man whose presence I sense as I stand on the shore of this lake, wrapped in early evening. I feel the anguish of one grown inarticulate, numb, dangerous.

The water is calm in the gentle rain. I reach up and turn off my headlamp to stand in darkness. Suddenly I am fully here with this lake and its powers. Suddenly I am susceptible to this place.

In the dark I shall tell you that I am a fugitive, not unlike this man. It is why I canoed across ponds and lakes and beaver dams to this spot this evening. It is why I resigned my professorship and moved to this wilderness, far-flung from the metropolis.

Like my silent companion, I am empty of living, breathing words. The words that cling to me are no longer a presence, no longer “part of the res itself,” no longer “part of the reverberation of a windy night as it is.”[2] I speak a language uncoupled from the world, occupying the space “left vacant by the world’s disappearance.”[3] I am a man made of metaphors, codes, and symbols. I have become one of those whose life, in the words of Wallace Stevens, consists of “propositions about life” and not of life itself. “The human reverie,” he continues,

is a solitude in which

We compose these propositions, torn by dreams,

By the terrible incantations of defeats

And by the fear that defeats and dreams are one.

The final stanza is devastating:

The whole race is a poet that writes down

The eccentric propositions of its fate.[4]

Rilke takes up the theme: we are onlookers, “looking at, never out of, everything! / It overfills us. We arrange it. It falls apart. / We rearrange it, and fall apart ourselves.”

Who has turned us around like this, so that

always, no matter what we do, we’re in the stance

of someone just departing?[5]

Who has turned us around like this? Language has. “As soon as mankind ceases to ‘reverberate’ to the world, the sickness penetrates language.”[6] It is the disease of the Great Forgetting.[7]

It is this that drove me to an appointment with this man’s spirit by a wilderness lake this evening, as if I might find an answer—the beginning of healing, a restoration. Perhaps something of the redeeming vision vouchsafed to Wallace Stevens in “The Idea of Order at Key West”:

She was the single artificer of the world

In which she sang. And when she sang, the sea,

Whatever self it had, became the self

That was her song, for she was the maker. Then we,

As we beheld her striding there alone,

Knew that there never was a world for her

Except the one she sang and, singing, made.[8]

Stevens. Rilke. Add W. H. Auden, E. E. Cummings, Emily Dickinson, T. S. Eliot, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Thomas Carlyle, G. K. Chesterton, Ted Hughes, Mary Oliver, Vasko Popa, Gary Snyder, Arseny Tarkovsky, Dylan Thomas, and many others who have struggled to find a way out of the solipsistic discourse of humanism. “Alas, where are we?” implores Rilke, lost in the labyrinthine echo chamber that defines the modern age;

Drifting freer and freer,

like kites torn loose from their strings

we lurch about in midair, frayed by laughter,

ripped by winds.[9]

Were I a real scholar, I could tell you that I am conducting scholarly research on language, hoping to find better words within the flasks and smoking test tubes of a laboratory, or digging out an ancient tomb to uncover lost powers of speech. But that would not be true. The truth is that I am a man ripped by winds, a man who abandoned research and dismissed the class and shook hands with colleagues to be here tonight in a spring rain. To turn off this light and listen. For what? I confess I don’t know.

Throw away the lights, the definitions,

And say of what you see in the dark . . .

“But do not use the rotted names,” chides Stevens. “How should you walk in that space”—this wilderness, this night—“and know / Nothing of the madness of space?” “Throw the lights away!” He means it. He’s desperate.

Nothing must stand

Between you and the shapes you take

When the crust of shape has been destroyed.[10]

That’s it. The crust of shape. Shaped by language more and more removed from this space where I now stand in darkness, in spring rain, listening. Waiting.

Imagine a voice sounding over a vast waste of land, and not only over the emptiness alone but over human beings; wherever you be in that great space you have but to listen and you take the voice entire―entire though yet with a difference.[11]

A magician who became a philosopher once told me that to hear is also to be heard.[12] This is the way of the universe, he said, whether we comprehend it or not. (Did he realize that he had strayed into Neoplatonism, I wonder? ‟In the pure Intellectual . . . the vision and the envisioned are a unity; the seen is as the seeing and seeing as seen. What, then, is there that can pronounce upon the nature of this all-unity?”[13]) An observation like this recasts the whole proposition of human discourse. I turn off the light and try to believe that the lake in this rain has heard my anguish over words.

There are loons out there in the darkness. I paddled by several, cruising the surface, earlier in the day. Loons suddenly stab the water with their bills and vanish beneath this world’s skin. Eskimos have told me that loons will speak to you if you are troubled. They are powerful and healing.

These wise red-eyed divers are my companions tonight on the skin of the lake and beneath it. Listening, they hear—I think—my quarrel with words. They begin their conversation. From lake to lake they speak.

This is the language I crave this evening. There was an Eskimo who set off one spring day looking for eggs. As he guided his kayak, he heard two loons calling. He turned his boat toward the calls and after much searching found their nest, tucked the eggs inside his parka, and continued on his way.

Then he heard them behind him. “That man,” they called, “that man who was going that direction in his kayak! Why has he taken our eggs? Why has he taken our eggs when we have fed him?” (For the man had just caught a muskrat.) They fell silent. Now they spoke again. “That man who is going away in his kayak! Why is he taking our eggs when we have given him a long life? We have granted him a long life!”

But he kept on going. The Yup’ik woman who told me this added, “It’s a true story.”[14]

Loons call again this evening, lake to lake in the rain. They hear me and see me and must know that I am looking for a true story.

For years I have told my students stories of the world the aboriginals lived within. Stories of animals who are at once people. Animal people. Like us human people, except they are moose people or loon people or beaver or bear people. But the modern age tells me it is certain the stories are not true. Oh, how I wanted them to be true! Yet I was never able to prove them truthful, after all. I felt I was a fraud. I imagined that one day, one of my students would knock on the office door and ask if we might talk. I could see her quietly seating herself and gazing out the window at the blue winter sky, then saying softly that the myths were wonderful. “But they can’t be true, can they?” Just dreams, her eyes would say, meeting mine.

I resigned before the knock ever came. I felt like the Wizard of Oz bailing out ten minutes before Dorothy unmasks him. Even so, I could hear her reproach as I fled the campus: “You’re a bad man,” she would scold in her youthful disappointment. And I knew I would answer as he did. “No, my dear, not a bad man. Just a bad wizard.”

I stand by this lake this evening, a bad wizard. Wondering if there is any truth to these stories after all. Wondering if their seeming improbability is a result of their inherent wildness. (For isn’t wildness always incalculable, immeasurable?) Wondering if there was ever a language of wildness: a language humans once shared with a sentient, conscious earth. And if so, can the modern mind ever know it again?

I contemplate the loon feather that floated by my canoe earlier in the day. I plucked it from the water and have cherished it ever since. The curious thing is how it has two eyes. The tip is black save for these two white circles of eye, as it were, on each side of the shaft. They are translucent; put your eye up to the white patch, and you can see through the finely spaced barbs. A loon has eyes on its back and wings.

The loon is a vision allowing us to penetrate the membrane of human perception into another realm of knowledge that only it discerns. “That man! Why has he taken our eggs when we have fed him and given him a long life?” Loon plucks us out of ourselves through its language, which I heard this evening, just as that Eskimo in his kayak did. But with a difference: Eskimos hear loon in the same place of mind where language literally speaks to them, whereas I hear loon someplace else. As the call of a wild creature, yes, but as actual language, no. I doubt loon will ever speak to me as we normally imagine speech. But that possibility is of little concern to me right now. The task is not to bend loon speech around so it can duplicate human speech; the goal is to bend human speech so it may be again harnessed to the speech of the earth.

I have come here this evening to begin a conversation with wildness—with mankind’s beginning. I have come to gaze through the eyes of a feather and listen through the voice of a lake diver. To begin to understand what Thoreau called “the Common Sense.”[15] To learn an origin of the human tongue that is not merely human after all. Something tells me this will happen not on a university campus but in a wild place like this, where mankind confronts a consciousness that devours our own, incorporating us but not defining itself by us alone.

This is the lesson of mythology and, in fact, of physics: that we belong to a much larger consciousness than we currently know; that we were created to participate in the earth’s conversation with itself, in the language of the gift. Our sorrow, our anguish, is that in our conversation of science and modernism we have dropped out of this vast wild discourse. It is an anguish born of the greatest separation of all: modern man’s exile from the conversation of the earth. The Eskimo who understands loon and wears loon’s masked face at his dances and sings loon songs does not suffer that separation, for he is not a modern man at all. It is I who feels the pain. I, possessed by a voice that is mine alone.

In the dark I close my eyes and see myself as a child. We lived surrounded by wild woods and marshes and a vast river, a place fit for a child’s turn of mind. I grew my voice here in conversation with winter storms, autumnal winds, spring floods and peepers and trillium, summer cicadas and crickets.

It was only when I became a man and “put away childish things” (St. Paul and Rousseau[16]) that I was led to speak and write of things with no cicada or cricket rasp to them, no limb-cracking wind about them; no red wings, no blue lake ice, no ruby throat. Texts without mergansers and goldenrod; a language with no waves or curious shoreline. My words became empty shells, void of the sea and earth and sky, for words surely die when they no longer resonate with hummingbird, trillium, mud, moonlight, and aspen. We are left with mere husks—symbol, metaphor, code, analogy, and mimesis.

The Austrian poet and essayist Hugo von Hofmannsthal (1874-1929) experienced a hollowing out of language uncannily similar to mine, revealing it to the literary world in a 1902 essay titled, ‟Ein Brief,” now known as the ‟Chandos Brief” or ‟Letter of Lord Chandos.” There was a time, he says, when he felt the presence of Nature in everything. ‟Everywhere I was in the center of it, never suspecting mere appearance.” He refers to ‟something entirely unnamed, even barely nameable” manifesting itself, ‟filling like a vessel any casual object of my daily surroundings with an overflowing flood of higher life.” ‟The whole thing is a kind of … thinking in a medium more immediate, more liquid, more glowing than words. It … forms whirlpools, but of a sort that do not seem to lead, as the whirlpools of language, into the abyss, but into myself and into the deepest womb of peace.”

All this somehow leaves him. He endeavors to find it in classical mythology. ‟As the hunted hart craves water, so I craved to enter these naked, glistening bodies, these sirens and dryads, this Narcissus and Proteus. . . . I longed to disappear in them and talk out of them with tongues.” To no avail. He is overcome ‟by a terrible sense of loneliness. I felt like someone locked in a garden surrounded by eyeless statues.” Words become meaningless. ‟I have lost completely the ability to think or to speak of anything coherently.… The abstract terms of which the tongue must avail itself as a matter of course… crumbled in my mouth like moldy fungi.”

His writing days, he says, are over. He is empty. Like the man whose presence I feel this evening, von Hofmannsthal yearns for ‟a language none of whose words is known to me, a language in which inanimate things speak to me.” A language ‟in which I might be able not only to write but to think.”[17]

Is Ezra Pound getting at this when he refers to ‟the crust of dead English, the sediment present in my own available vocabulary”? ‟Rossetti,” he remarks wistfully, ‟made his own language. I hadn´t in 1910 made a language. I don´t mean a language to use, but even a language to think in.”[18]

I believe I have come to the same impasse. My shadow by the lake stirs uneasily. Nobody remembers what drove him into the wilds beyond the communal hearth, beyond geography, beyond the reach of names, to the place where loons speak lake to lake. Then silence. Stillness. As if waiting, listening for a presence that focuses everything upon the still point of meaning which neither he, nor, centuries later, von Hofmannsthal or I understood.

Here something uncanny happened. He was visited by a Redeemer known to the Iroquois as Peacemaker, the genius behind the Great Law of Peace that binds together the Six Nations even today. The Redeemer’s name was Deganawidah, though Iroquois consider it too sacred to say aloud. (I shall write it, and not speak it.)

Deganawidah was born of a virgin in Huronia, on the north shore of what is today Lake Ontario. In a dream his mother and grandmother learned that he would grow up to be an instrument of righteousness and peace. He was different, say the Iroquois, from other children.

One day the young man told his mother he would soon leave on a long journey to find the soul of discord and fear and heal it. His mother watched in sorrow as he hewed out the white stone canoe that would take him across the great lake. When it was finished, he embraced his mother and grandmother. They asked how they would know whether he was dead or alive. Take a knife and cut into a tree, he said. “If the sap flows, I am alive. But if blood drips . . .”

So far this sounds like the story of the Eskimo and the loon: a fantasy. A child is miraculously born of a virgin; he grows older and travels in a stone canoe; and his life is somehow incorporated into the tissues of a tree (see “nonlocality” in Lecture 7). Anthropology dismisses the whole thing as a myth: an ancient tale, perhaps grounded in a vague, remote fact, that has taken on supernatural embellishment through repeated telling. Such tales provide a necessary validation for the society that believes in them, anthropologists and folklorists say, although they don’t for a moment believe them to be literally true. Deganawidah was certainly not virgin-born; he never could have crossed Lake Ontario in a stone canoe; a tree could not possibly reveal his fate.

The Iroquois, however, believe this story, including its seemingly supernatural details. Many still believe it. One of my students, a Mohawk, retold the story to the rest of his class. The young man had grown up with Mohawk tradition, including the language, and as he spoke, he made it clear that this was not fiction. I glanced around the room and saw incredulity on the faces there.

The issue again is language. Notice how Peacemaker can communicate with the earth in ways that seem to us not just extraordinary but incomprehensible. It is not enough to say that these feats validate his authority and guarantee his message’s longevity among zealous followers. The power of the story is deeper, more alarming. I shall return to this later; for now I merely want to draw attention to the breadth and potency of Peacemaker’s language.

When Peacemaker arrives in the country of the Iroquois on Lake Ontario’s south shore, a group of fugitive hunters tells him that the Five Nations are slaughtering and eating each other. Peacemaker strikes out through the wilderness to find the most notorious cannibal of them all.

Eventually he reaches the man’s lodge. It’s empty. He climbs onto the roof to await the monster’s return.

Soon enough a lone figure approaches through the thickets, bent under the body of another man. Peacemaker watches as the fugitive butchers the corpse and drops the morsels into a large cauldron of boiling water. As the surface of the water begins to settle, the fugitive sees a face gazing back at him—a handsome face, a face of serenity and goodness. (It is the Huron’s, gazing down through the smoke hole into the cauldron.) The fugitive mistakes it for his own. He’s smitten. “How can such a face belong to a man who commits the evil I do?” his concealed visitor hears him say.

In an instant the reflection vanishes. With a loud crack of splitting wood, Peacemaker springs from the roof of the lodge and lands, catlike, several feet away. Slowly he uncoils to his full height, holding the monster steadily in his gaze, refusing to relax his grip on his eyes.

The stranger had unusual powers, say the myth tellers. He had—language. A different language. Incarnate language. Performative language. Improbable, ridiculous words of grace. He called it the Good News. He seemed to speak from somewhere deep inside things—the ground, the trees, the wind. No matter how preposterous his words might be, his listeners wanted to believe them.

This was the man who holds the hissing, cursing cannibal with his eyes, refusing to release him, to let him reach for the knife. Slowly, evenly, the Huron speaks from some primal place. A man can eat only what he is given, he says, just like the suckling infant. Grace abounds, he says; fear is illusion. He speaks with the force of mountains and trees and myriad lakes and all the animal host.

They must bury the dead man’s body, says the stranger. He directs the mesmerized cannibal to bring a cauldron of fresh water to a boil while he, the man made of healing words, goes off to find proper food.

When the fresh pot is starting to bubble, Peacemaker returns through the clearing with a buck slung across his shoulders. This is humankind’s food, he declares as he eases the deer to the ground. The gift of animal flesh. The fleshy coat of our kinsmen, the deer people. Flesh that must be treated courteously, with ceremony.

Like a fever, the witchery breaks. The monster, bathed in sweat, is cleansed. The horror passes. Peacemaker now does something curious. He sings to the empty man, filling him with a new name. E-a-watha, he pronounces him. Hiawatha: still remembered by the Iroquois as a formidable leader.

The two part ways. Hiawatha returns to Onondaga to take up domestic life once more. Peacemaker journeys east to the land of the Mohawk to preach his cause.

Hiawatha returns, rejoicing, to his wife and daughters.

But evil is still abroad; witchery is not entirely vanquished. As Evil turns its baleful gaze upon this man, clothed and in his right mind in the embrace of family, Death memorizes his name. As each daughter reaches marriageable age, she is conjured against by the sorcerer Thadodaho. One by one the daughters perish. When only Hiawatha and his wife are left, the pitiless sorcerer hurls one more curse, causing the accident whereby his wife, too, is killed.

She is pregnant.

Splitting the sky with his grief, the Redeemer’s disciple becomes a woodland wanderer once more, dangerous and irrational, for this is how the Iroquois explain those overwhelmed by grief. The only language he has now is sorrow and revenge, but he refuses to speak it. No, not a cannibal this time, for he is decisively defeated. Even his will to live has been erased. He will carry his wound alone till death overtakes him, an old bull moose gently lowering itself to the mossy ground beside a lake.

The man who walks to his death walks firmly, though in a haze. A dark, inexorable logic drives him on.

Two years after our ghostly lakeside encounter, I make this walk.

________________

Footnotes

[1] I am about to relate the story of Hiawatha and the Peacemaker, a narrative sacred to the Five Nations Iroquois. There are many versions, the most authoritative being found in Matthew James Dennis, “Cultivating a Landscape of Peace: The Iroquois New World” (PhD diss., University of California at Berkeley, 1986), 29–33. For a truncated, politicized version that looks like the author caved in to an overzealous editor, see Matthew Dennis, Cultivating a Landscape of Peace: Iroquois–European Encounters in Seventeenth-Century America (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1993), 76–115. The version I recount is distilled from numerous sources I have read and heard over many years.

[2] Wallace Stevens, “An Ordinary Evening in New Haven,” in Selected Poems (London: Faber & Faber, 1953), 135.

[3] Gerald Bruns, Modern Poetry, 190.

[4] Wallace Stevens, “Men Made Out of Words,” in Selected Poems, 90.

[5] Rainer Maria Rilke, “The Eighth Elegy,” in Duino Elegies: Rainer Maria Rilke, trans. Edward Snow (New York: North Point, 2000), 51.

[6] Marcel Detienne, The Creation of Mythology, trans. Margaret Cook (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986), 9.

[7] The phrase “Great Forgetting” is borrowed from Daniel Quinn, The Story of B (New York: Bantam, 1996).

[8] Stevens, “The Idea of Order at Key West,” in Selected Poems, 77–79.

[9] Rainer Maria Rilke, “Sonnet 26,” in Sonnets to Orpheus: Rainer Maria Rilke, trans. Edward Snow (New York: North Point, 2004), 111.

[10] Wallace Stevens, “The Man with the Blue Guitar,” in The Collected Poems of Wallace Stevens: Corrected Edition, ed. John N. Serio and Chris Beyers (New York: Vintage, 1982), 194.

[11] Plotinus, ‟Imagine a voice”

[12] David Abram, “Natural Magic,” Minding the Earth: Newsletter of the Strong Center for Environmental Values 4, no. 2 (June 1983).

[13] Plotinus, ‟In the pure Intellectual” note; ‟The Intellectual Principle is a seeing which itself sees” note.

[14] Story told by Marie Meade, Bethel, AK, July 16, 1996.

[15] Henry David Thoreau, The Maine Woods (New York: Harper & Row, 1987), 95.

[16] Saint Paul: 1 Corinthians 13:11 (AV). Rousseau: “Lettre I de milord Edouard, Cinquième partie,” in Julie, ou la nouvelle Héloïse (1761).

[17] Hugo von Hofmannsthal, ‟The Letter of Lord Chandos” (1902), passim.

[18] Pound, Literary Essays, pp. 193-194. I have changed his punctuation.