The Great

Forgetting

Calvin Luther Martin, PhD

October 27, 2024

With thanks to Clairejouy

Aldous Huxley

Niels Bohr: “Manifold” is a term we will encounter in quantum reality

The Swimmer

But to say, “I know, too, that the blackbird is involved in what I know”—this is beyond me.

Wm. Faulkner, Nobel laureate in literature

Mt. Katahdin, Maine

Carl Jung, MD

Huxley

Only one of them had the courage to inquire, “What do you want?” and stay to listen to the response.

It was a grizzly bear track. Huge and fresh in new autumn snow. What’s more, I knew that the author of this message was hunting me. I had lived with Raven’s Children, the people we call Eskimos, who had been hunted by walrus and moose and even blizzards. So they told me.

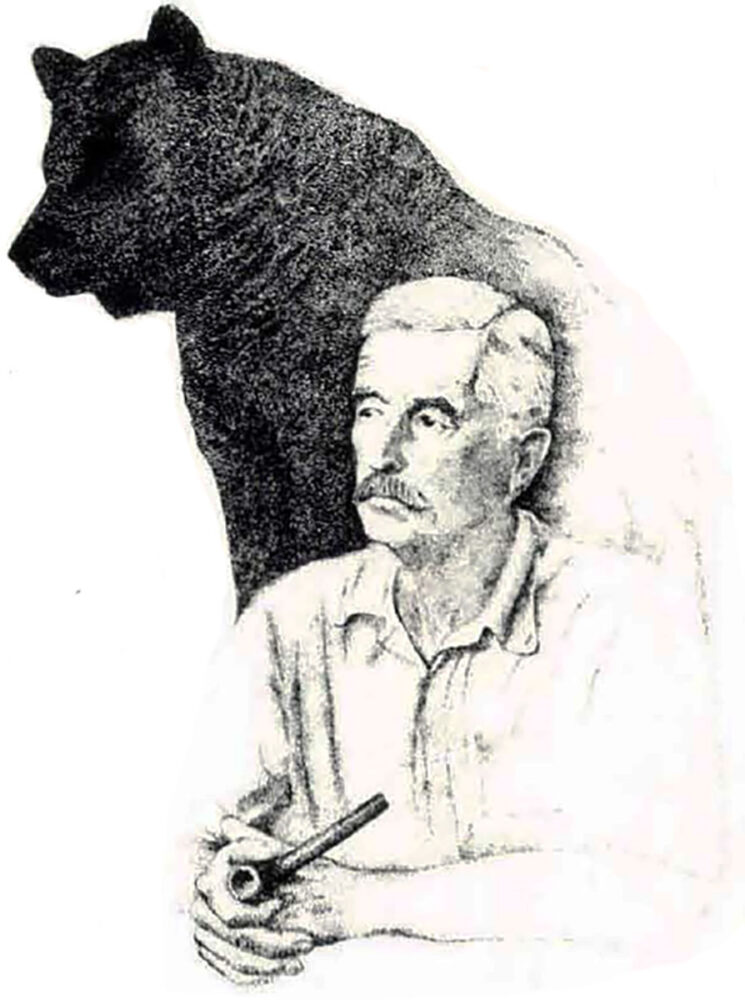

I was alone with no gun. It knew that too. Just as Old Ben, the massive Dark One in William Faulkner’s “The Bear,” knew young Ike McCaslin was alone, without a weapon.[1]

Like McCaslin, I was vulnerable.

Dark One? Eskimos won’t discuss bears. At least not without considerable resistance and—what to call it? Agitation? Maybe that’s the best word. “Bears got ears on the tundra,” Charlie Kilangak confided in me one day, quietly yet emphatically. They were listening as we mentioned them that moment, he meant.

For two years I had lived in Raven’s world, where I began to see reality as the Real Human Beings, as the Eskimos call themselves, view it.

I know noble accents

And lucid, inescapable rhythms;

But I know, too,

That the blackbird is involved

In what I know.[2]

Blackbird. Raven. Same thing. The lines belong to Wallace Stevens. Their reality, however, belongs to Charlie Kilangak, a thickset man with the bearing of a walrus, who taught me there’s no such thing as talking about animal people. Talking about them is no different from speaking to them. (There are human people and animal people in Raven’s world. Jarring, yes, to modern ears.) People like Charlie Kilangak know it’s always better to use a vague, indirect, yet respectful term. Like Dark One, or Grandfather, or Old One.

I had studied this cosmology for decades as an academic. Studied and taught it. Still, I was not prepared to live by its terms.

Recall the meeting with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, where the Yup’ik elder Paul John warns the state biologist that moose are powerful, and if the moose don’t support the kass’aq’s plans for managing them, they won’t cooperate. (As noted before, Yup’iks call all whites kass’aqs. From Cossack, the word for the first Europeans they met.) The kass’aq smiles. He doesn’t believe a word of it. (Over time I will get to know this man. Genial and a superb field biologist, he knows the old man’s veiled warning is, for all practical purposes, nonsense.) There is more to the story of this man than I disclosed earlier—something that, to discuss, would collapse the amassing harmony of Raven’s world. All I can say is there are no coincidences and no accidents in this place. Cause and effect are beyond human understanding. And certainly there is no such thing as “luck”; Eskimos convinced me of this.

Somehow they know it’s all orchestrated, choreographed. Wallace Stevens’s “amassing harmony” seems appropriate.[3] I was witnessing a cosmology where ‟there is complete identity of Knower and Known.”[4] That’s why one must be a real person, living there; “real” meaning someone who participates in the place’s Mind at Large, its Real-Being. Real-Being is ‟no blind thing, but is seeing, self-knowing, the primal knower.”[5]

I was definitely not a participant. Obviously, neither was my biologist friend. We were not real people within what we perceived to be a vast featureless, treeless bog, floating on not rock but frozen mud, sand, water, with the wide-open sky dreaming like eternity upon it.

So it was in the beginning. ‟Seeking nothing, possessing nothing, lacking nothing,” a place indistinguishable from the ‟One”—if Eskimos cared to use western philosophical language, which, of course, they don´t. It ‟is perfect,” continues Plotinus, ‟and, in our metaphor, has overflowed, and its exuberance has produced the new: this product has turned again to its begetter and been filled and has become its contemplator and so an Intellectual-Principle”—Mind at Large.

All life belongs to it, life brilliant and perfect; thus all in it is at once life-principle and Intellectual-Principle, nothing in it aloof from either life or intellect: it is therefore self-sufficing and seeks nothing: and if it seeks nothing this is because it has in itself what, lacking, it must seek. It has, therefore, its Good within itself, either by being of that order—in what we have called its life and intellect—or in some other quality or character going to produce these.[6]

This is a perfect description of the Yup´ik concept, yua. Yua had contours and living, replicating plants and animals. Still, it was nameless. The place of tundra cotton, blueberries, cranberries, creatures furred, feathered, and finned, air, stones, water, and, in due course, human beings. Even so, it bore no name. When humans arrived, it was “the place where we are.” The place that fed and altogether took care of us. The place of our being.

The Navajos and Eskimos I have lived with have a term for such a place. In fact, virtually all aboriginal societies use the same expression: they call the place “themselves.” We are the people, they say. The Real People. What they mean is: We are this place. We live because of this place and it thrives because of our ceremonies and courtesies. This place is alive—sentient, conscious, intelligent. It has mind. We share this mind. (Apache Indians will tell you that “wisdom sits in places” within this mind-space.[7])

Indeed they typically declare that they have lived in this place since time out of memory, even though scholars ‟prove” that these people´s ancestors moved here, say, twenty generations earlier. Please understand that the objection of these logical positivists (archeologists and anthropologists) is meaningless. Our Western perception of time means nothing to these people. (Aldous Huxley gives us insight into this timeless mindset in the novel, ‟Island,” when Will Farnaby experiences a ‟timeless yet ever-changing Event—something that words could only caricature and diminish, never convey. It was not only bliss, it was also understanding. Understanding of everything, but without knowledge of anything.[8])

One can take this further. The Real People don’t make sense outside this place. They live by the grace of animal and plant beings and other chthonic powers of this place. This happens in part through the relationship anthropologists call totemism, a nineteenth-century term for the uncanny consciousness—for it is consciousness, after all, that we are really talking about—shared by humans and animals among people like Yup´ik Eskimos.[9] A better way to approach this complicated subject is through Neoplatonist philosophy, which is complex in its own way; and yet, being an elaboration on Plato´s concept of the Idea (which has been long familiar to Western philosophy and even Christianity), Neoplatonism may help illuminate what is really transpiring in this human-animal conversation. ‟Consciousness, as the word indicates, is a conperception,” explains Plotinus, ‟an act exercised upon a manifold,” where ‟an agent turns back upon itself, upon a manifold.” The manifold he refers to is the Intellectual-Principle, a phenomenon sprung from the One.

Seeking nothing, possessing nothing, lacking nothing, the One is perfect and, in our metaphor, has overflowed, and its exuberance has produced the new: this product has turned again to its begetter and been filled and has become its contemplator and so an Intellectual-Principle.[10]

‟Manifold” is a term we will encounter again in quantum reality. (Hang on to this word.) In Paleolithic cosmology, as with the Neoplatonic Intellectual-Principle, ‟there is complete identity of Knower and Known . . . not by way of domiciliation [domestication] . . . but by Essence, by the fact that, there, no distinction exists between Being and Knowing. We cannot stop at a principle containing separate parts; there must always be a yet higher… principle above all such diversity.” Notice ‟no separate parts” and a ‟higher principle above all such diversity”—a perfect description of the human-animal relationship. Elsewhere, Plotinus asks, ‟What if the total combination were supposed to be of one piece, knower quite undistinguished from known so that, seeing any given part of itself as identical with itself, it sees itself by means of itself, knower and known thus being entirely without differentiation?”[11]

You get the idea. The ‟totemism” crowd, starting with Henry R. Schoolcraft and continuing with James Frazer et al., started at the wrong end of things. Aristotle accused his predecessors of the same mistake: ‟They began by laying down a general proposition that satisfied, or was even demanded by, their intelligence, and then tried to arrange the facts in harmony with it. The consequence was that their starting-point had no firm attachments to the real subject of investigation, and their deductions led them to more or less unfruitful and insecure results.”[12]

The concept of ‟totemism” should have been trashed long ago. (Nietzsche, a master of invective, would have called it an abortion.[13]) Nevertheless, with the understanding that I am incorporating the above gloss into its deeper meaning, I shall continue to use the term from time to time as a convenient abbreviation for conperception-within-a-manifold.

Back to the way of the human being as defined by the Real People. Conperception-within-a-manifold (see the puffin, below), medicine, healing, language, food are all mediated through the Place Who We Are. A Real Person of This Place is absolutely present and participatory, and knows how to discourse with moose, bear, caribou, seal, walrus, ptarmigan, tundra swan, cranberries, blueberries, herring—and, ah, salmon, the Swimmer.

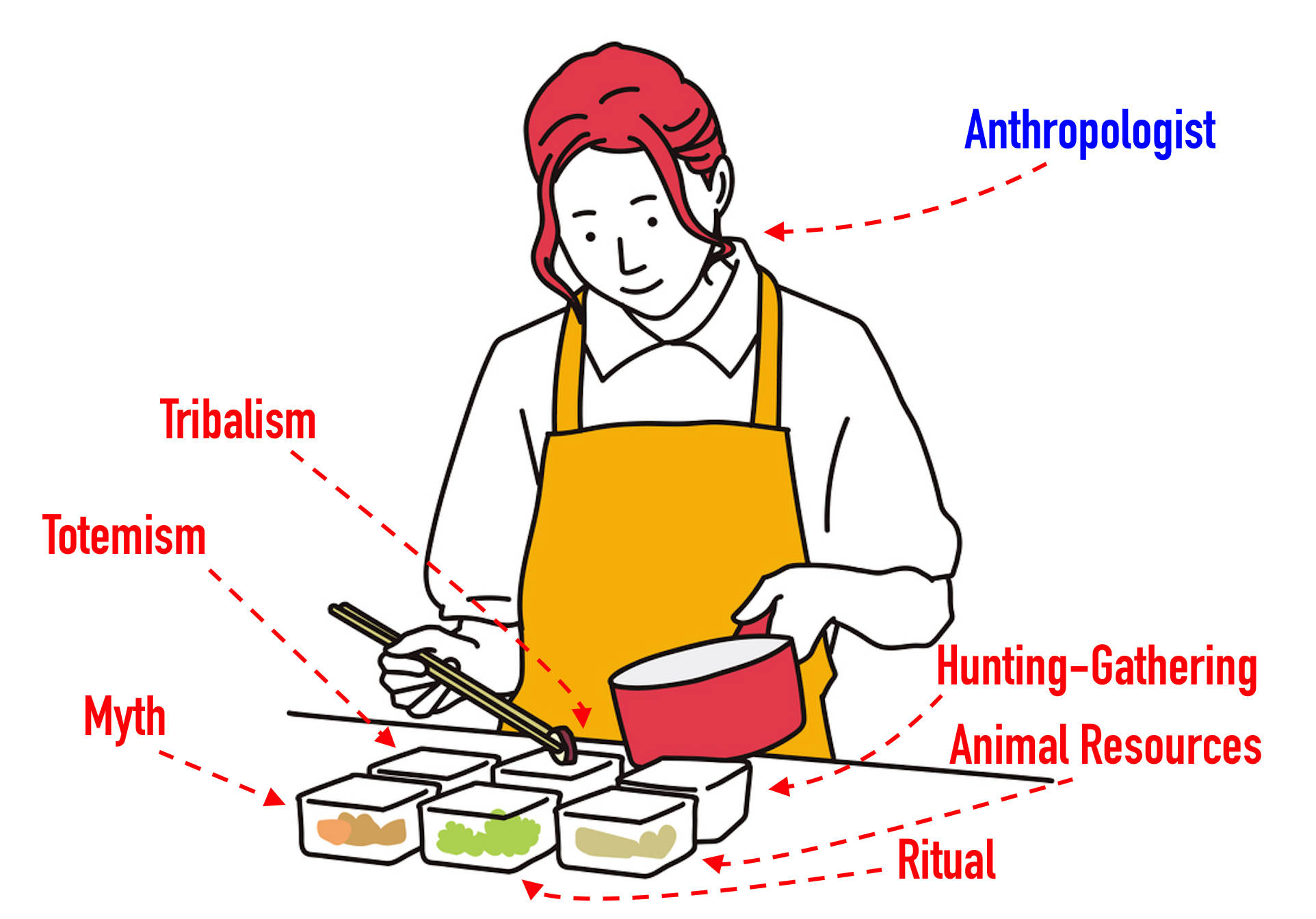

Oh yes, my biologist friend and I knew Yup’ik culture academically: sliced and diced, freeze-dried and stuffed, as it were, into handy containers labeled ‟world view,” ‟totemism,” ‟myth,” ‟hunting-gathering,” ‟tribalism,” ‟subsistence,” ‟food quest,” ‟ritual,” ‟animal resources,” etc. In fact, Randy Kacyon was married to a native, an Athapaskan woman, as I recall. He and I could talk about this place and its animal host as Aristotelian categories and Cartesian objects, but we couldn’t speak them or be spoken of or dreamed by them. We had no sense whatsoever of Huxley’s Mind at Large.[14]

“I know noble accents and lucid, inescapable rhythms”—yes, I can lay claim to this. But to say, “I know, too, that the blackbird is involved in what I know”—this is beyond me.

This is why I write all of this down. I am long retired from academia, and at the point where I don’t need to read newspapers or yet another good book, or, frankly, sit through another Bach recital. More than anything, I need to know if the Dark One is involved in what I know.

I have camped in Alaska by rivers and ponds and in forests where wildness lives, where bears abound. I bend over and touch a footprint with my hand. I once set up my tent in a spot by a stream frequented by bears. The moist black earth told me that the Dark One came to drink. A day or so later the trail took me by a lake; the dirt path passed over a beaver lodge tucked into the side of the bank. Suddenly there was an arresting scent. I laid my pack aside and walked back and found the smell issuing from a tiny vent at the top of the lodge. Dropping to hands and knees, for the first time in my life I inhaled beaverness.

Print of bear in black mud, musk of beaver drifting up from the dark interior of a lodge—this is the essential consciousness and language of the child: pungent, tactile. It is not for nothing that the child learns to speak even as he is putting the things of the world into his mouth: he must taste it to speak it. The child grasps the world, and as he does, it grasps him in turn. The world pours through the child, and on the way it speaks to him. Language starts as a conversation of the sensual: mutual feeling, mutual smelling and tasting, mutual hearing and seeing. It is as my Neoplatonic magician friend put it: when we hear we are being heard, when we see we are being seen.[15]

I like to think this is what Huxley meant by Mind at Large, and Stevens with his amassing harmony. What captivates me is the conviction that living in this harmony and in this mind comes naturally when we are children.

I want it back. The only problem is, I’m not sure I can find or recognize the path again.

There are two paths. Neither takes you.

Sometimes, though, lost in thought, the one

lets you go on.[16]

Rilke’s lines mock me. (I apply them to myself, despite his writing them with another purpose in mind.)

Bears got ears on the tundra. Moose hear us as we discuss them. This isn´t anthropological data from a container labeled ‟myth”; it’s what I have seen and been told by people who knew it was so. What I say in the pages that follow is an effort to come to terms with two massively different realities—mine and theirs—with the haunting thought that their reality was once mine, and somewhere deep down may still be.

It was a grizzly bear track, huge and fresh in new autumn snow: the Dark One’s imprint, offering a return, a restoration to a fugitive armed with all the wrong words. And since they were the wrong words, they were dangerous, and I was dangerous. The Dark One knew this.[17]

Hesitantly I lifted my foot, paused, and plunged into—contact! A “streak of reality / broke in upon this stage.”[18] (No, not fear. I want to be clear about this. The sensation was not entirely comfortable. Let me be clear about this, too.) A force ancient and essential to the shaping of human nature suddenly enveloped me. I knew I was standing on the sacred ground of wildness, within the precincts of a consciousness vaster than my own. Undulating, loose-limbed wildness had passed this way just moments before, leaving its clawed imprint to devour me with the terrible, ancient question: What is man, if not the handiwork of wildness?

I am not alone in being seized by this question. In the crashing tonnage of a sperm whale Herman Melville experienced “some colossal alien existence without which man himself would be incomplete.”[19] For Faulkner, the question loomed in the figure of an old bear in a Mississippi wilderness. “So I will have to see him,” resolved the boy Isaac McCaslin, “without dread or even hope. I will have to look at him.” What was this boy “born knowing, and fearing too maybe, but without being afraid, that [he] could go ten miles on a compass because he wanted to look at a bear none of us had ever got near enough to put a bullet in and looked at the bear and came the ten miles back on the compass in the dark”?[20] Faulkner frames the question through one of his characters. Surely it is the oldest existential question of all, the one that refuses to be silenced by modern man’s faculty of reason.

What was I born knowing and fearing (but without being afraid) that compelled me to seek out the “wild immortal spirit” of a huge bear? “Not even a mortal beast,” continues Faulkner, “but an anachronism indomitable and invincible out of an old dead time.”[21]

Or is it the other way around? Did the wild immortal spirit seek me? “Lost in his freedom, Man pursues / The shadow of his images,” warns Auden. And yet it need not be this way. Perhaps on some long-neglected axis of reality, it is never this way. Perhaps, as Auden writes in his next line, “the Unknown seeks the known.”[22]

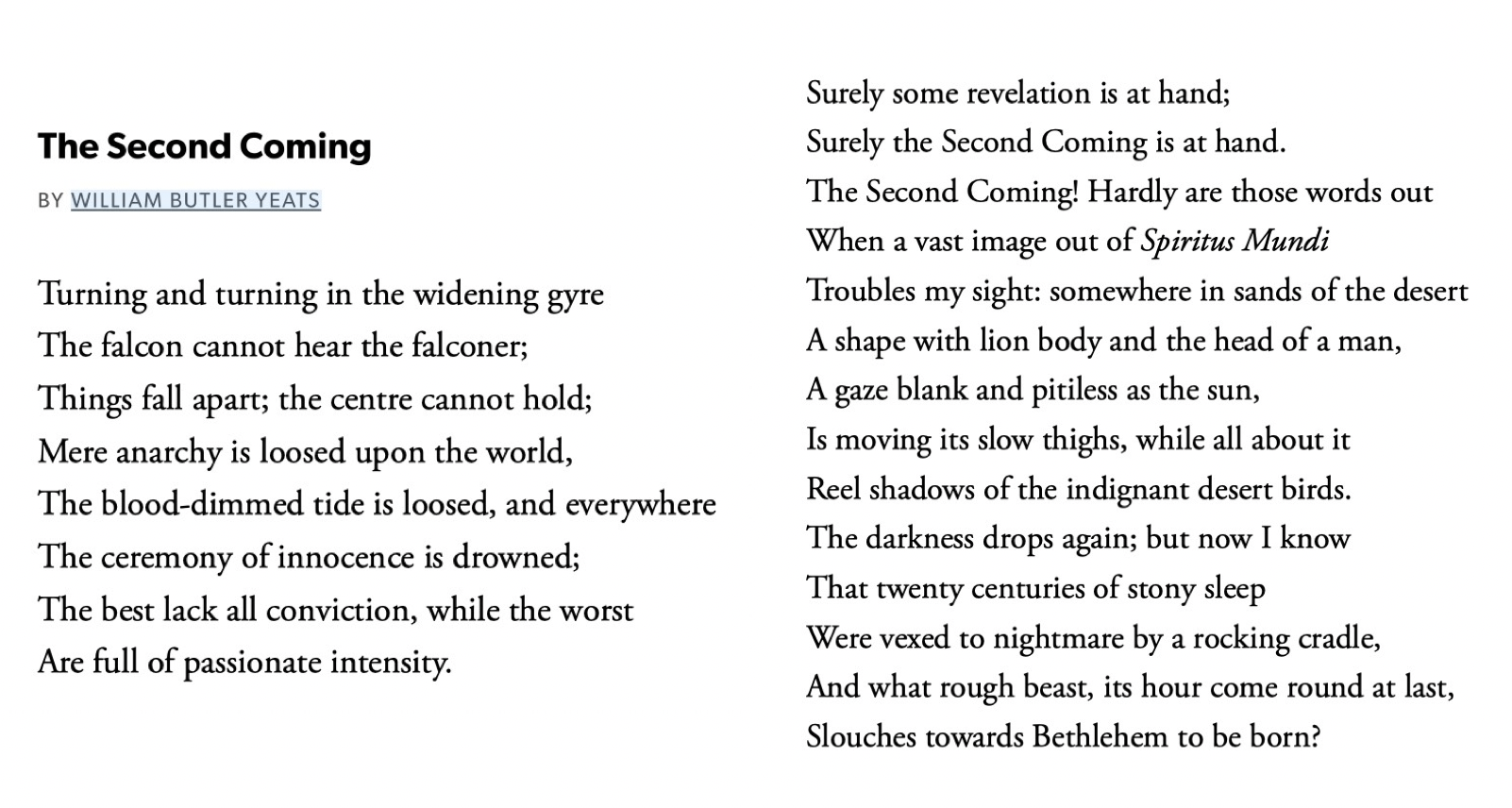

The Unknown. “Hardly are those words out / When a vast image out of Spiritus Mundi / Troubles my sight.”[23] Surely this Unknown (W. B. Yeats’s Rough Beast, Rudolf Otto’s Mysterium Tremendum, William Blake’s Ancient of Days), surely this is divinity? A great Middle Eastern sky god? A towering, wrathful Jehovah!

No. None of these. The Unknown is wildness.

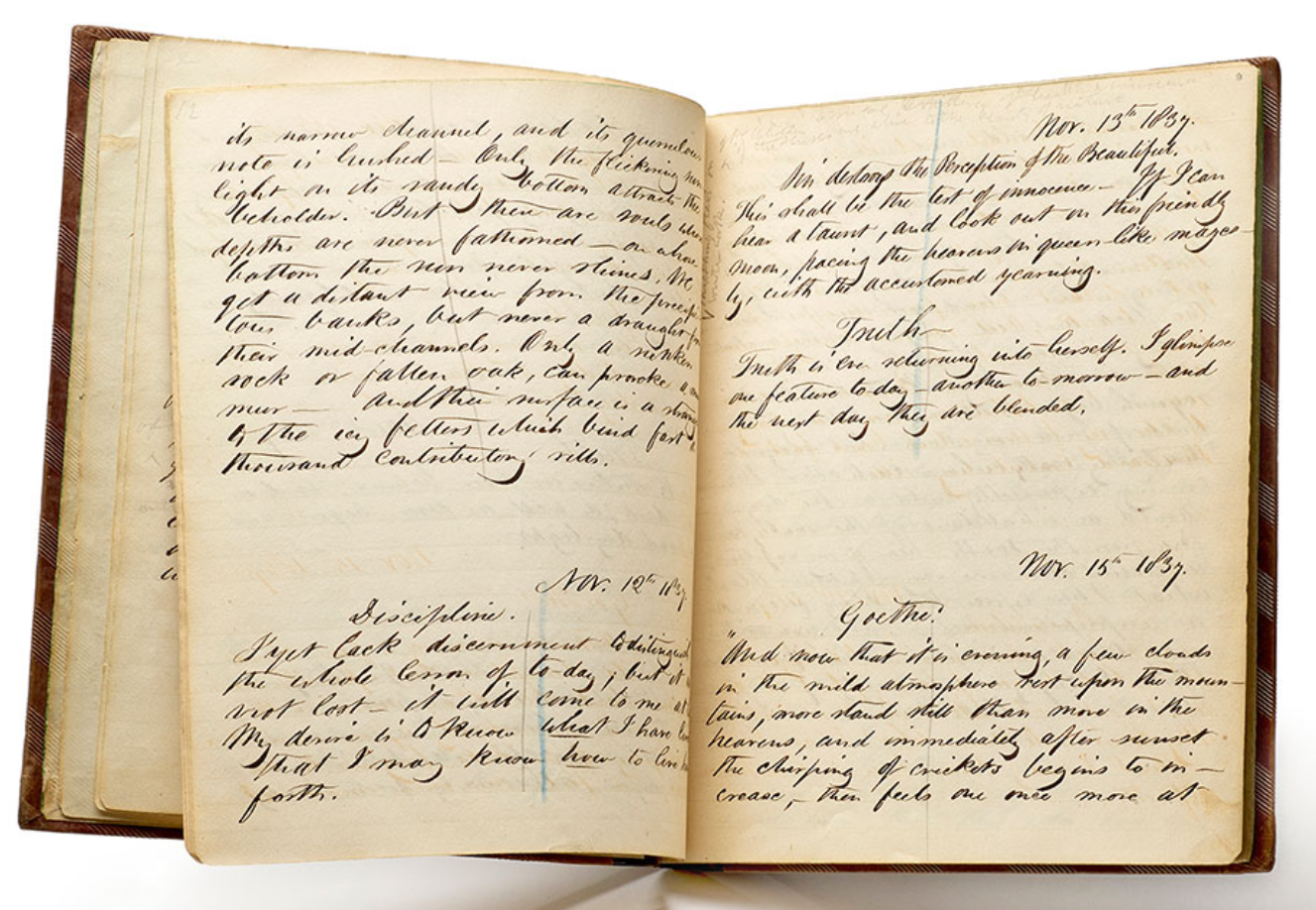

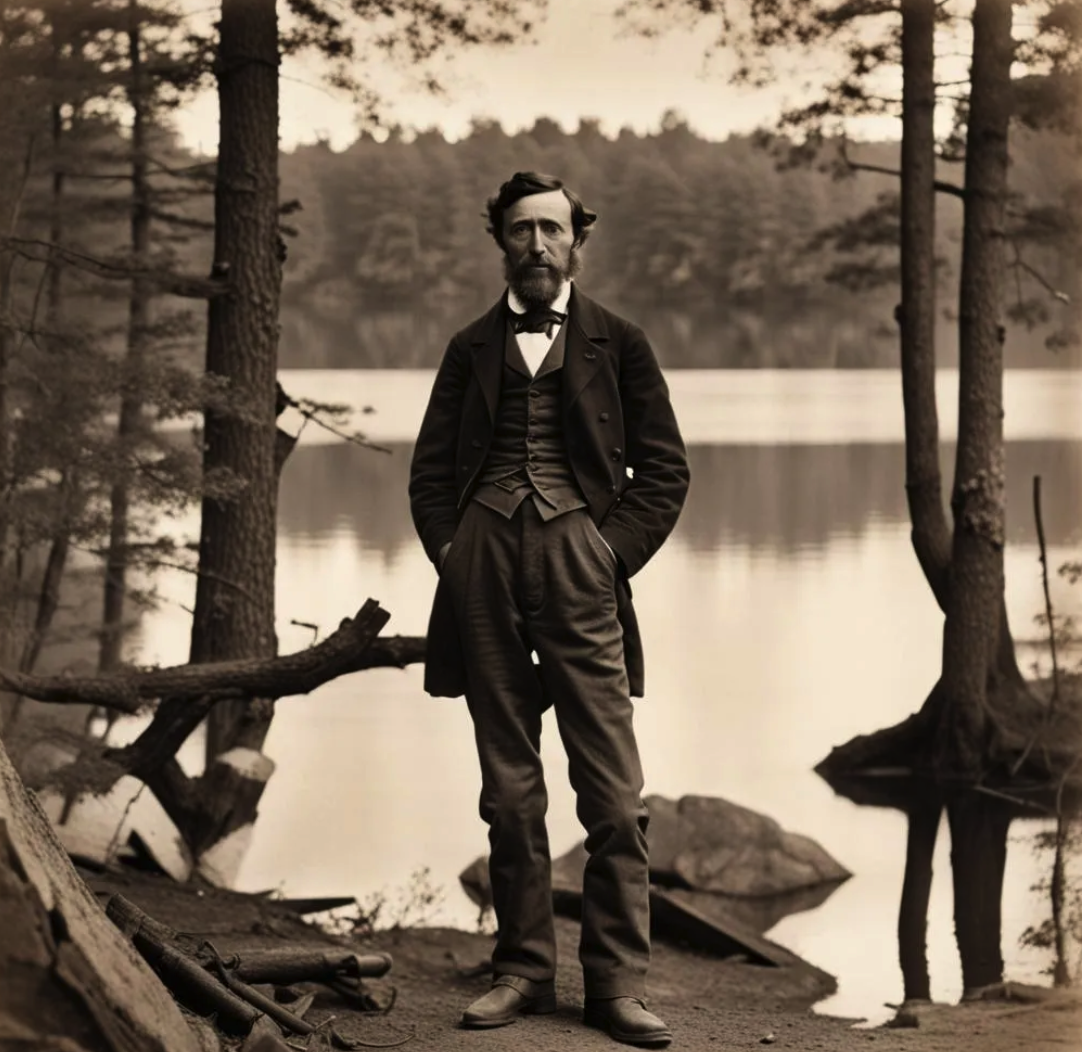

Thoreau would discover this on a camping trip in the Maine wilderness. Alone in the swirling mists at Katahdin’s summit, he felt a great energy moving near him. “What is this Titan that has possession of me?” “Contact! Contact!” he shouts into the pages of his journal. “Who are we? Where are we?”[24] The sober author of Walden was in a place not controlled by man, “untouchable, impenetrable and impalpable.”[25]

The mountain awakened with “a force not bound to be kind to man,” Thoreau noted, chillingly.[26] So did the untouchable, impenetrable, impalpable uncertainty that wrestled with Jesus of Nazareth for forty days and nights, that kneaded him as if to change his shape.[27] Forty days in the presence of something language cannot reach. Carl Jung, in search of the primal mind on a trip through equatorial Africa, found himself perilously close to the same experience. “The trip revealed itself as less an investigation of primitive psychology . . . than a probing into the rather embarrassing question: What is going to happen to Jung the psychologist in the wilds of Africa?”[28]

This was a question I had constantly sought to evade, in spite of my intellectual intention to study the European’s reaction to primitive conditions. It became clear to me that this study had been not so much an objective scientific project as an intensely personal one, and that any attempt to go deeper into it touched every possible sore spot in my own psychology.[29]

“I had wanted to know how Africa would affect me, and I had found out,” Jung reminisces to his biographer. Africa’s message to the distinguished leader of the Bugishu Psychological Expedition was stark: “The primitive was a danger to me.”[30]

So it is to all of us, Dr. Jung. A scientific investigation into primitive psychology backfired into an explosive encounter with the First World of conperception-within-a-manifold, where “all things are crouched in eagerness to become something else,”[31] where the psychologist risked becoming something changed. Jung found himself poised to ‟know as he was known.” The phrase is the Apostle Paul’s who borrowed it from Neoplatonism, and it is a bombshell.[32] It marks the watershed separating where the wild things are from where the domesticated things are.

The First World bubbles just beneath the surface in each of us. Carl Jung would agree. Jung would also agree that, as children, we are born into this chthonic consciousness (ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny), and, he would add, we ignore this deep, wild-visaged consciousness at the peril of our sanity. “Whenever we give up, leave behind, and forget too much, there is always the danger that the things we have neglected will return with added force.”[33] (Echoing Jung, Huxley called it “the festering remains of a past that refuses to die.”[34])

Notice that with wildness, the fulcrum of consciousness shifts ominously. Thoreau senses the mountain thinking him even as he thinks it, an experience he finds confounding. The man who was eager to have “intelligence with the earth,” who famously believed that “in wildness is the preservation of the world,” had reached the border of strangeness—the nameless, boundless, ravishing consciousness of the Unknown—and found it terrifying.[35]

For Jung, “the spell of the primitive” meant chaos.[36] There was no telling (read: no controlling) what it might do to him if it had its way. To a mind that ran like a Swiss watch, this was unacceptable. Jung closes a letter home to his wife with these words: “I do not know what Africa is really saying to me, but it speaks.”[37]

I don’t believe him. He knew all too well what Africa was saying. The truth is, he lost his nerve and fled its searing message.

It was as if . . . I knew that dark-skinned man who had been waiting for me for five thousand years. . . . I could not guess what string within myself was plucked at the sight of that solitary dark hunter. I knew only that his world had been mine for countless millennia.[38]

“There was,” Jung continued, “the danger that my European consciousness would be overwhelmed by an unexpectedly violent assault of the unconscious psyche”—the same Unknown that wrestled with Thoreau on Katahdin and with Jesus in the Judaean wilderness.[39] All three were confronted by “some ancient, inexhaustible, and patient intelligence” that dwelled within the landscape itself and now demanded their attention.[40] (Only one of them had the courage to inquire, “What do you want?” and stay to listen to the response. Unfortunately his followers and posterity demonized the encounter and magicked it into a militant religion founded foursquare on the myth of good versus evil.)[41]

“Why should life tremble before the unexpected,” asks Loren Eiseley, recalling a mountain descent not unlike Thoreau’s, “if it had not already anticipated the answer? There was no order. Or, better, what order there might be was far wilder and more formidable than that conjured up by human effort.”[42] The theoretical physicist David Bohm would call it the implicate order—the reality of the quantum potential.[43] And, yes, it’s unnerving.

This, I know now, is what drove me into the wilderness that autumn morning: my need to encounter this far wilder and more formidable order, to literally stand within its “warped indentation in the wet ground,” as Faulkner writes, “which while he looked at it continued to fill with water until it was level full and the water began to overflow and the sides of the print began to dissolve away.”[44]

And so I stood.

_________________

Footnotes

[1] William Faulkner, “The Bear,” in Three Famous Short Novels (New York: Vintage, 1961), 185–316. “The Bear” appeared originally in Faulkner’s Go Down, Moses (1942).

[2] Stevens, “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird,” in Selected Poems, 45.

[3] Stevens, “It Must Give Pleasure,” 124.

[4] The phrase is from the Neoplatonist, Plotinus, describing what he called the cosmic Intellectual-Principle.

[5] Plotinus on Real-Being

[6] Plotinus, Real person

[7] Keith Basso, Wisdom Sits in Places: Landscape and Language among the Western Apache (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1996).

[8] Huxley, Island, p. 325, emphasis his.

[9] See J. G. Frazer, Totemism (1887). Henry Schoolcraft was using the term in 1853. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the word was first used by the Englishman, John Long, in his Voyages and Travels of an Indian Interpreter and Trader (1791) in North America. The OED says the word´s etymon may be the Ojibwa nindoodem and Nipissing atoteman.

[10] Plotinus, Enneads.

[11] Plotinus, Enneads.

[12] Cornford, Intro., p. 4

[13] Nietzsche, Twilight, passim

[14] Huxley, Doors of Perception, 23–24.

[15] Abram, “Natural Magic.”

[16] Rainer Maria Rilke, “In a Foreign Park,” in New Poems, 1907, 107.

[17] I recommend reading John Berger, “One Bear,” in his Keeping a Rendezvous (New York: Vintage, 1992), 132–37.

[18] Rainer Maria Rilke, “Death Experienced,” in New Poems, 1907, 111.

[19] Loren Eiseley, Francis Bacon and the Modern Dilemma (Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries, 1962), 94.

[20] Faulkner, “The Bear,” 198, 241.

[21] Faulkner, “The Bear,” 186, 188.

[22] Auden, “For the Time Being,” 222.

[23] W. B. Yeats, “The Second Coming” (1921), in The Collected Poems of W. B. Yeats: A New Edition, ed. Richard J. Finneran (New York: Macmillan, 1983), 187.

[24] Thoreau, Maine Woods, 95, emphasis his.

[25] John Archibald Wheeler, “Bohr, Einstein, and the Strange Lesson of the Quantum,” in Mind in Nature: Nobel Conference XVII, Gustavus Adolphus College, St. Peter, Minnesota, ed. Richard Q. Elvee (San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1982), 7.

[26] Thoreau, Maine Woods, 94.

[27] The “kneaded him” phrase is from Rilke, “Man Watching,” 122.

[28] C. G. Jung, Memories, Dreams, Reflections, ed. Aniela Jaffé (New York: Vintage, 1961), 273.

[29] Jung, Memories, 273.

[30] Jung, Memories, 274, 272.

[31] Peter Beagle, quoted in Loren Eiseley, The Star Thrower (New York: Times Books, 1978), 53.

[32] Paraphrase of 1 Corinthians 13:12 (King James Version; henceforth, KJV). See W. R. Inge, ‟The Permanent Influence of Neoplatonism upon Christianity.”

[33] Jung, Memories, 277.

[34] Aldous Huxley, Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Other Essays (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1952), 9-10.

[35] Thoreau, Walden; or Life in the Woods (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1948), 113; Thoreau, “Walking” (1851).

[36] Jung, Memories, 242.

[37] Jung, Memories, 372.

[38] Jung, Memories, 254–55.

[39] Jung, Memories, 245.

[40] Eiseley, Star Thrower, 183.

[41] See Nietzsche, Twilight of the Idols, pp. 131-132. ‟For Jesus himself had done away with the concept ‘guilt’—he denied any gulf between God and man, he lived this unity between God and man, it was this that constituted his ‘glad tidings’. . . . And he did not teach it as a privilege! Thenceforward there was gradually imported into the type of the Saviour the doctrine of the Last Judgment, and of the ‘second coming’, the doctrine of sacrificial death, and the doctrine of resurrection, by means of which the whole concept ‘blessedness’, the entire and only reality of the gospel, is conjured away in favour of a state after death!” For this and other sins, Nietzsche pronounces Christianity ‟most profoundly nihilistic” (Twilight, p. 213).

[42] Eiseley, “The Innocent Fox,” in The Unexpected Universe (New York: Harcourt, Brace and World, 1964), 202, emphasis mine.

[43] Bohm, Wholeness and the Implicate Order.

[44] Faulkner, “The Bear,” 202.