The Tragedy of the Garden

Calvin Luther Martin, PhD

November 1, 2024

“Like 1000 plates tumbling off the kitchen shelf”

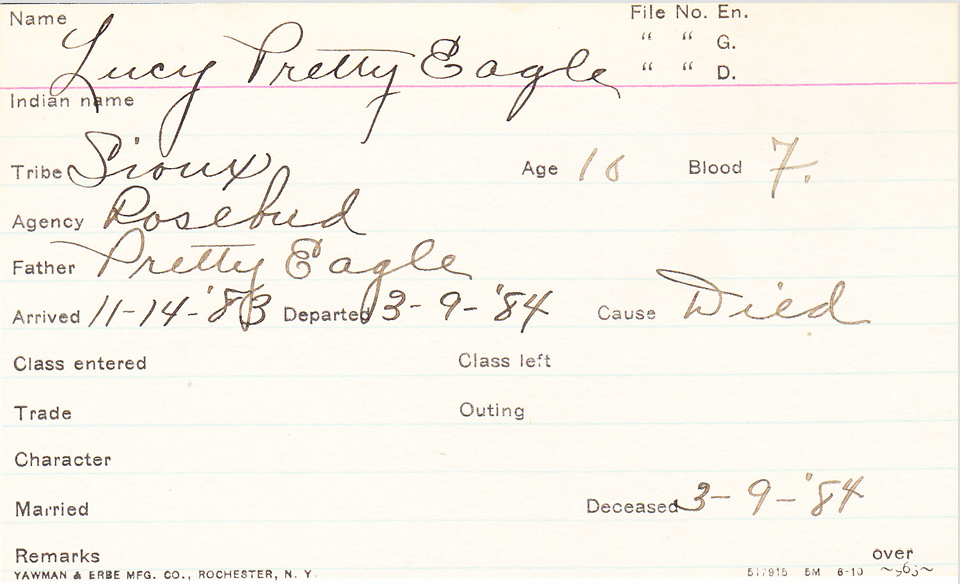

Death certificate for Lucy Pretty Eagle, the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, Carlisle PA. Many of the hundreds of Indian children who died at the school, died of tuberculosis. When Lucy's father was notified of her death by the superintendent, he wrote back that she had already died the year before she was transported to the school.

Click on the image to hear a fragment of Maxie Altsik’s story

Good versus Evil

Wm. Blake’s “New Jerusalem” descending to earth (and chasing off the demons).

7,000 sheep

God’s adversary, Satan. The two locked in combat over mankind.

14,000 sheep

Springbok

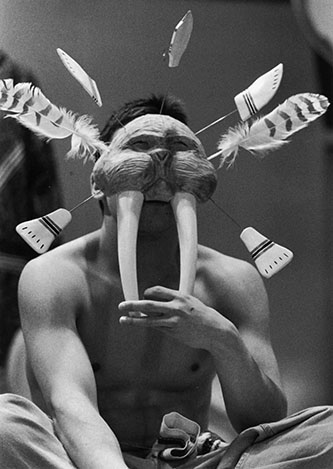

Aleingan (Kagoptinner) was a shaman. His name meant “The Grey-Haired One.” (Photo by Roald Amundsen)

San Bushman

The phantom mind paradox is the opposite of the phantom limb paradox. In this instance, you are told—or you tell yourself—that all 36" of consciousness are not present when in fact they are—and you are left with an inchoate yet profound sense of emptiness and loss. We all suffer from this. Me too. Formal religion pretends to fill this seemingly empty space, this "loss," and it fails. Indeed, religion is a major part of the problem—an obstacle preventing us from consciously living the entire "yardstick" of mind—escaping "time" into Huxley's Mind at Large.

“Which explains why the shaman whispered” (Netsilik photo taken by Roald Amundsen).

“The shattering of the flawless sheet of glass.”

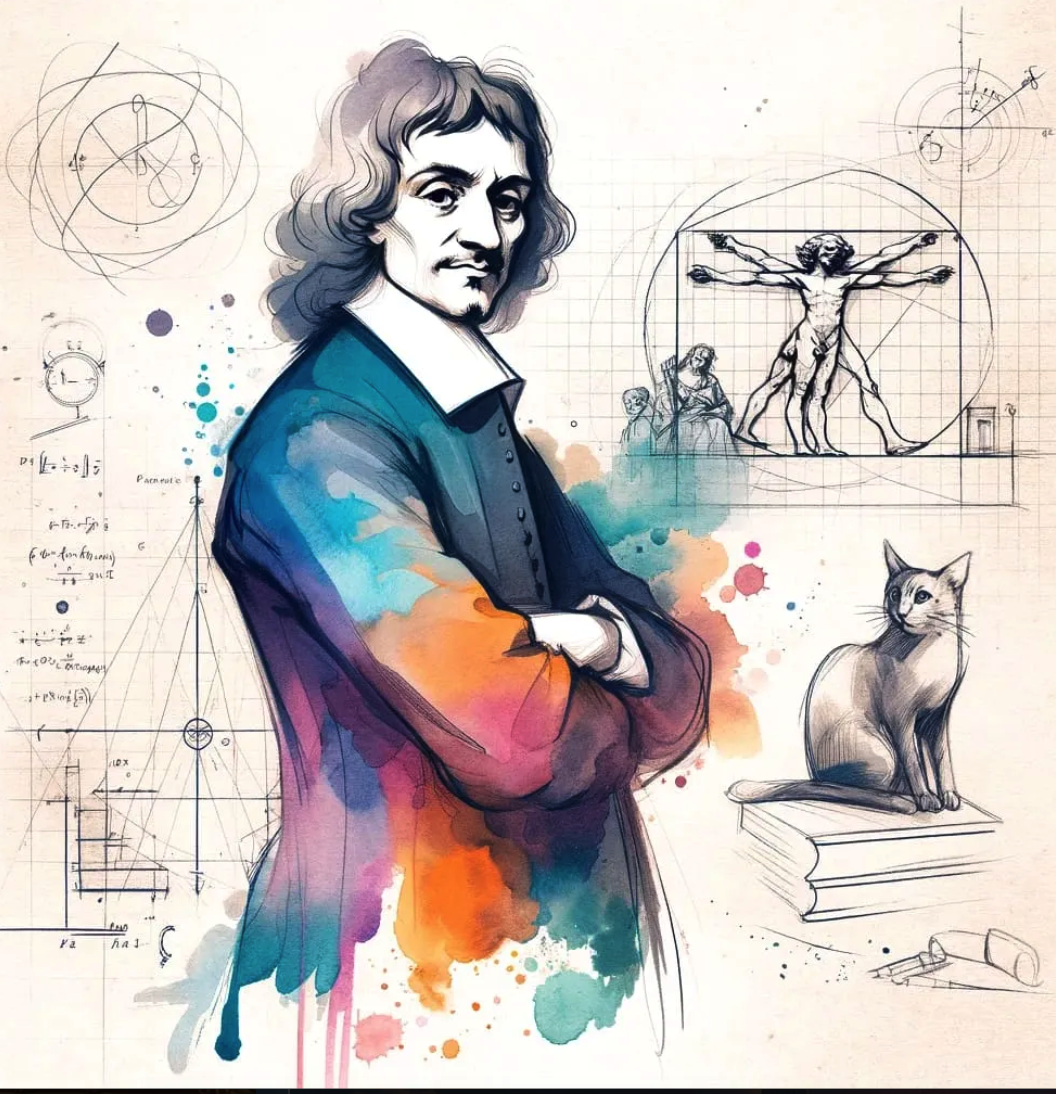

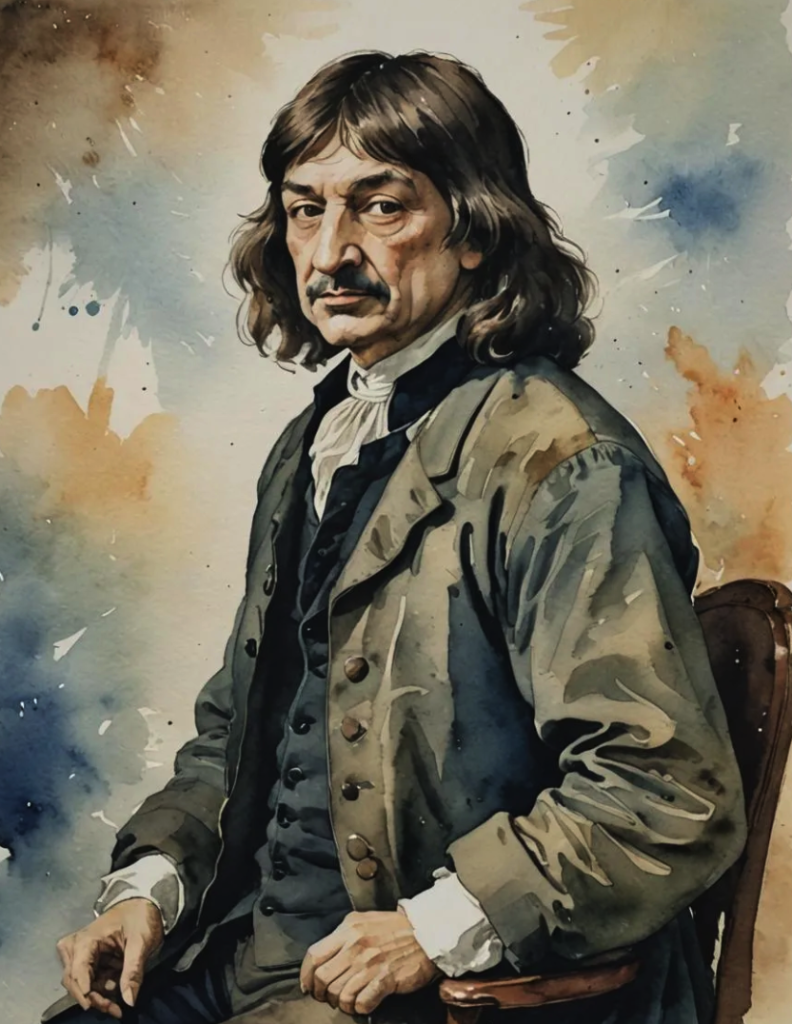

Descartes

“You are beautiful, Enkidu. You are like a god. Let me bring you into Uruk-Haven, to the Holy Temple, the residence of the gods.”

Yup’ik women in Tununak AK distributing seal meat (James Barker photo)

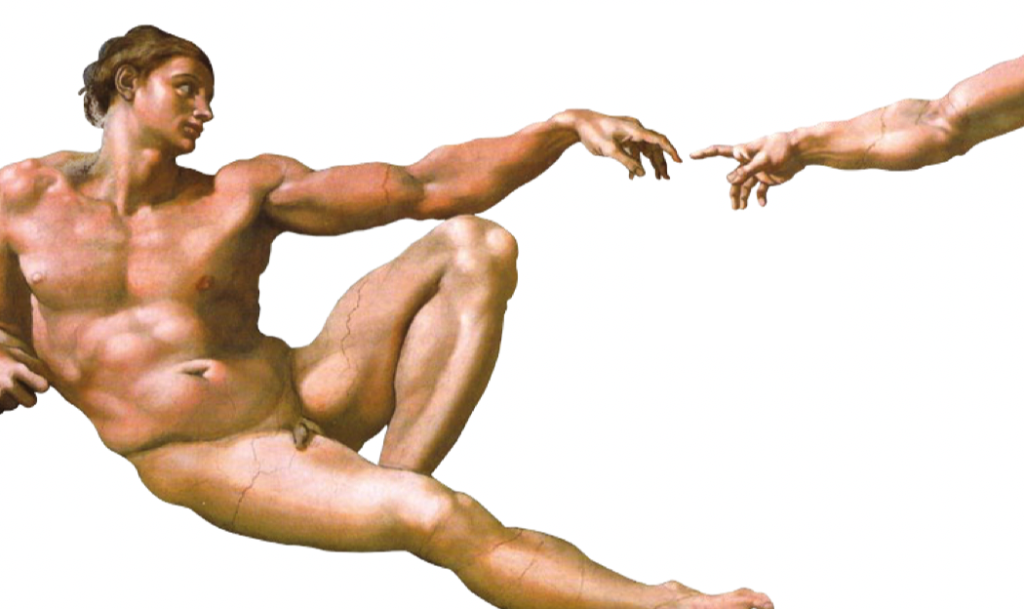

With a name like mine, I can be forgiven for thinking of Moses before the burning bush. Or Jehovah, on the dome of the Sistine Chapel, reaching out to touch Adam’s finger. Except that the conversation I joined was far older than that of a man before his god.

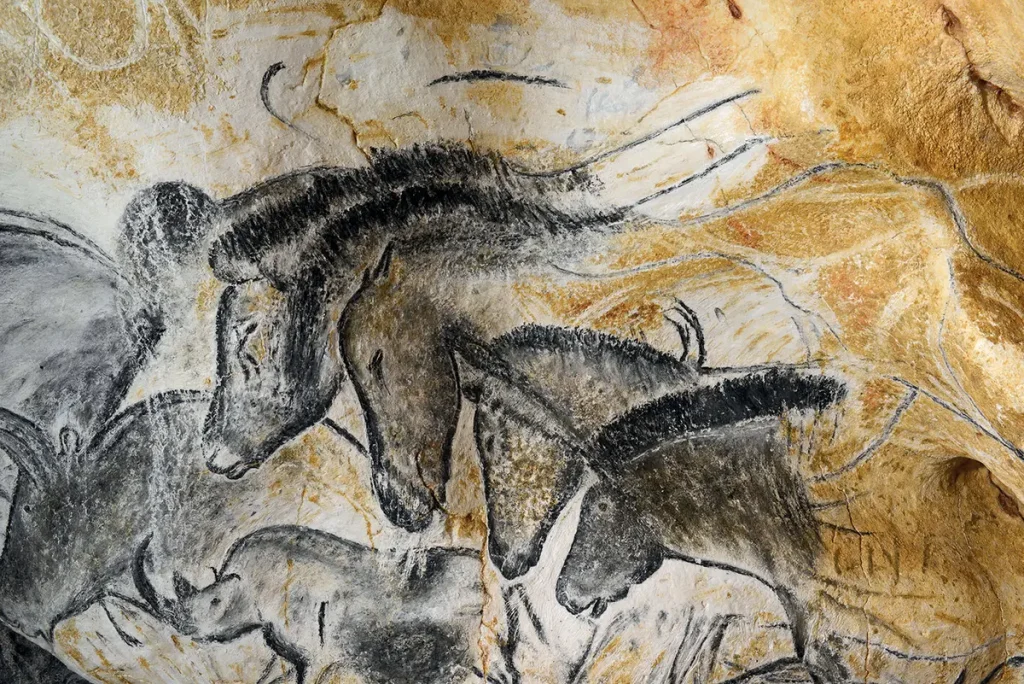

Long before the Middle Eastern invention of sky gods, our ancestors followed labyrinthine passages and corridors into the entrails of the earth to stencil their hands on smoky walls, reaching across a membrane of stone to touch and be quickened by the spirit of wildness. In the subterranean halls of Chauvet, Cosquer, Gargas, Pech-Merle, Cougnac, and later Lascaux, Roc-aux-Sorciers, Trois-Frères, Altamira, and La Mairie, walls ripple with bison, horses, oxen, lions. On the other side of the equator herds of eland, kudu, and springbok thunder by on open-air boulders in Namibia and Botswana. In Australia’s Arnhem Land, marsupial and man dream the same dream.

It is the conversation mankind has had with wildness since time immemorial. And it is not over. “Bears got ears on the tundra,” Charlie Kilangak says quietly, and I hear ten thousand years of Western history come crashing down like a thousand plates tumbling off the kitchen shelf. Ten thousand years of the terrible fiction born of the great grain- and livestock-fed civilizations of the Middle East, the lie that wildness is finished, shattered by this one phrase.

The same thing happens when I witness Paul John discreetly deliver a message to the state biologist from the moose: Don’t interfere with us. (I would hear the same warning about radio-tagging the Dark One, the grizzly bear, and about fishing for the Swimmer, the salmon.)

Living with Eskimos shattered a lot of my cultural dishware. For them, wildness clearly had not ended; its deep ecology—conperception and its corollary, the gift—still worked, at least until Moravian and Russian Orthodox missionaries showed up to inform them that they were depraved and deprived, driving the message home with tuberculosis, whiskey, guns, and boarding schools. The missionaries succeeded only superficially. Even when dependence on the kass’aq world had been forced on the Eskimos, it was clear that in some uncanny way wildness still defined them.

As in the masked dances where I watched the broken-down drunk, Joe Chief Jr., transform into a breathtaking creature before hundreds of Eskimos. The auditorium throbbing with the beat of skin drums and men singing as this young man, who was regularly locked up in the Bethel prison, effortlessly shape-shifted into, I swear, the sorcerer of Trois Frères. The audience was thrilled. Adam’s Wall—mankind on one side, beast on the other—was demolished that evening.

Or the long story told one winter afternoon at the Bethel Senior Center by that master storyteller Maxie Altsik, speaking Yup’ik, sometimes barely audibly, to the spellbound elders. He insisted that I record him, though I felt as intrusive as I did when I stepped into the grizzly bear print. The man is now dead, yet his voice and story remain alive on my tape, and from time to time I listen to his conversation with the wild things.

Or the shamanic masks collected from villages all over the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta and displayed one week in Toksook Bay, the village of Paul John, where the old people gathered for one last grand conversation with these wild beings that—quietly, secretly—had survived the missionary bonfires.

They survived because Raven’s Children never truly believed in the great Middle Eastern combat myth, in which cosmos (order) eternally fights chaos, and good and evil “lurch, wrestle and twist in their purposeless war”[1] (a paradigm so embedded in me that I was named after two of its greatest champions, John Calvin and Martin Luther).

Charlie Kilangak told me earnestly that he was, of all things, a puffin. His exact words (he wrote them down): “I am a puffin . . . from my ancestral tree and in blood. And my son is too,” he added, eyeing me, just in case this son of Adam standing before him might get the mistaken impression that puffins could disappear anytime soon.[2]

Does a man who is a puffin go to heaven? Does he have a soul? Did Jesus die for his sins?[3] Come to think of it, can he have any sins?[4] Should I have explained to him that I am the man made of good and evil, born again of Middle Eastern sky gods?

In my two years with the Eskimos, I never met one who would understand the Egyptian agrarian god Ra crawling out of the chaotic, undifferentiated ocean (Nun), the two locked in eternal combat thereafter. Or the Mesopotamian agrarian storm god Marduk defeating freshwater (Apsu) and saltwater (Tiamat). Or India’s agrarian Indra battling the great chaos of the cosmic waters (Vritra). Or agrarian Ahura Mazda of Zoroastrian Persia battling evil Ahriman. Or the mighty Baal, Canaanite god of agrarian order and cursed in Hebrew scripture, pitted against the sea serpent Yam, and Mot: the desert, underworld, and death.

The reason is simple. Puffin was not created by gods of field and flock, gods that lurch, wrestle, and twist in their purposeless war of good versus evil. Which explains why the prison where I met Charlie was incomprehensible to this man who handed me a slip of paper whereon was penciled mankind’s oldest consciousness: I am a puffin.

“With all its eyes the animal world / beholds the Open,” writes Rilke.

Only our eyes

are as if inverted and set all around it

like traps at its portals to freedom.[5]

When John Kilbuck arrived, Bible in hand, among the Raven’s Children, he showed them how they were horribly wrong, chapter and verse—and thousands of years of puffin, salmon, and seal came crashing down. The Word of God—being the word of guns, whiskey, tuberculosis, matches, flour and sugar and crackers and, of course, hymns and Bible verses—clearly showed them to be the fallen children of that other agrarian sky god, Jehovah, slayer of Leviathan and Rahab (the waters) and implacable enemy of Satan, the Prince of Darkness holding them in thrall. Shamans, dances, drums, masks, labrets, tattoos, skin clothing, men’s houses, sod houses, weird demonic fantasies of the animal world—they all would have to go.

Let there be no more of this puffin nonsense: they were human beings, Adam’s sinning offspring, pure and simple. Put on trousers, they were told; send your kids to boarding school, speak English, buy a gun, fight the good fight. Behave like the Anglo-Saxon men and women God meant you to be.

William Blake’s New Jerusalem would be “builded” among the dark satanic villages of this howling wilderness.

And did those feet in ancient time

Walk upon England’s mountains green?

And was the Holy Lamb of God

On England’s pleasant pastures seen?

And did the countenance divine

Shine forth upon our clouded hills?

And was Jerusalem builded here

Among these dark Satanic mills?

Bring me my bow of burning gold!

Bring me my arrows of desire!

Bring me my spear! O clouds, unfold!

Bring me my chariot of fire!

I will not cease from mental fight,

Nor shall my sword sleep in my hand,

Till we have built Jerusalem

In England’s green and pleasant land.[6]

From England to America to the banks of the Yukon and the Kuskokwim, the Good News seethed and flowed like hot lava.

Kilbuck, a Moravian, founded his New Jerusalem in a one-room seminary where, many years later, I taught the agrarian combat myth capped by Christ’s final triumph over Satan’s rebellion. And on a sunny spring morning, before a throng of their hymn-singing relatives and friends, I graduated seven Eskimo men and women as warriors of the cross.

But we were no match for Raven, the One Who Is, despite my liberal theology. Most of them figured out that a warrior of the cross, in any shape or form, was a warrior against the old ways. In typical Eskimo fashion, without confrontation or explanation, they melted away back to their native villages, scattered across the vast brooding solitude we call tundra. Back to bears, moose, caribou, geese, ducks, ptarmigan, seals, walrus, salmon, herring, cranberries, blueberries, salmonberries—the beings that listen to us.

I am talking about mankind’s earliest religion, the conversation with wildness. It was this conversation that the Middle Eastern myth of cosmic good versus evil would counterfeit. Bronze and Iron Age man would treacherously manufacture sky gods to certify humankind’s dominion over animal kin; animals would be offered up in sacrifice to the nostrils of Yahweh, Baal, Marduk, and Ra, or yoked to plow and chariot, their manure fertilizing tilled fields. By force, they would yield their flesh and hide and fur and milk. They would be reckoned as property and wealth.

“There was a man in the land of Uz whose name was Job,” reads the Hebrew Bible. “And that man was perfect and upright, and one that feared God, and eschewed evil. His substance . . . was seven thousand sheep, and three thousand camels, and five hundred yoke of oxen, and five hundred she asses, and a very great household; so that this man was the greatest of all the men of the east.”[7]

Contrast this with a man in the land of Raven whose name was Puffin, a man who had no truck with God and Satan’s quarrels over mankind’s allegiance. The reason being disarmingly transparent: the combat myth of good versus evil is irrelevant to someone not at war with the earth and its creatures.

At its core the story of Job is an ancient Semitic sermon on the righteousness of man’s dominion over the earth. (Francis Bacon must have loved this story.) The book begins with the bland observation that a man owned seven thousand sheep, three thousand camels, one thousand oxen, and five hundred donkeys, and ends, forty-two chapters of pious rhetoric later, with the same man owning twice this number: fourteen thousand sheep, six thousand camels, two thousand oxen, and a thousand donkeys.

To claim ownership of twenty-three thousand assorted fellow creatures by divine right is a stunning departure from the language of wildness. By the time the book of Job was written, something terrible and fantastic had happened to Middle Eastern man’s conversation with the earth. In the little books cobbled together in what we call the Bible, a sky god named Yahweh proclaims sovereignty over animals, and at the end of the day a farmer—a creature, in fact the only creature, made in Yahweh’s image—has doubled the size of his herds. It’s clear where this paradigm is headed.

Compare Job’s story to the little stories passed down among the Kalahari Bushmen (Ju/’hoansi), who say they shape-shift into springbok.[8] And at the end of the hunt, which is in fact a complex courtship, springbok becomes human and human becomes springbok, and neither owns the other since they are endlessly transmuting into one another. This is the essence of totemism.

Unlike the agrarian Hebrew Bible, where man is said to mirror God, in the Kalahari Desert human and animal seamlessly, fluently mirror one another.[9] “We have a sensation in our feet, as we feel the rustling of the feet of the springbok . . . making the bushes rustle. . . . We have a sensation in our face, on account of the blackness of the stripe on the face of the springbok. We feel a sensation in our eyes, on account of the black marks on the eyes of the springbok.”[10]

From the Kalahari to the Bering Sea, there are people who still speak this bedrock language of mirrored wildness. The Danish ethnographer Knud Rasmussen heard it when he visited the Netsilik shaman Orpingalik and wheedled some “magic words” out of him. “In communicating them to me,” Rasmussen recorded in his journal,

Orpingalik uttered them in a whisper, but most distinctly and with emphasis on every word. His speech was slow, often with short pauses between the words. . . . When I had received them, Orpingalik declared that these secret words, which we owned in fellowship, almost made us brothers. The spirits of life would regard us as one, as it were, and treat us the same if only we closely observed all the taboo that life required.[11]

The linguist Lucy Lloyd heard it too, when she casually asked a young /Xam San (Bushman) to throw away a fungus she had brought home to examine.

Shortly afterwards, some unusually violent storms of wind and rain occurred. Something was said to him about the weather, and /haṅǂkass’ō asked me if I did not remember telling him to throw the fungus away. He said he had not done so, but had “put it gently down.” He explained that the fungus was “a rain’s thing,” and evidently ascribed the very bad weather we were then having to my having told him to “throw it away.”[12]

On hearing such claims, my culture raises its eyebrows, sucks in its breath, and mutters “Charming, yes, but utter fantasy.” The stuff of juvenile imagination. Teddy bears and fairy tales.

At which point in the conversation I am liable to lay a yardstick on the table. Imagine the entire history of our kind being carried within those thirty-six inches. Start at zero (australopithecines) and run the eye along, inch by inch, spanning hundreds of thousands of years. Loren Eiseley called it “the immense journey.”[13] Homo habilis, H. erectus, H. sapiens. Neanderthal, Cro-Magnon, modern man. And finally Homo sapiens sapiens, no different from you and me anatomically or in brain capacity or function. (Even the fully modern human may be well over a hundred thousand years old.)

You and I embody the yardstick. Every inch of it. These ancestors are not bones on a shelf in a museum; they are our immanent kinsmen. We carry their genes, their errands, their psychology and spirit and consciousness.

Let me put it more vividly: they are alive in us. Not vanished; not even remote.

Stretch out your hand: they are alive in that hand. Speak: they are your voice and speech. “Tell me about despair, yours, and I will tell you mine,” writes the poet Mary Oliver[14]; know they are alive in your despair and mine.

We carry their genius of speech and reasoning, their unparalleled manual dexterity, their dreams and the host of stories that compelled them.

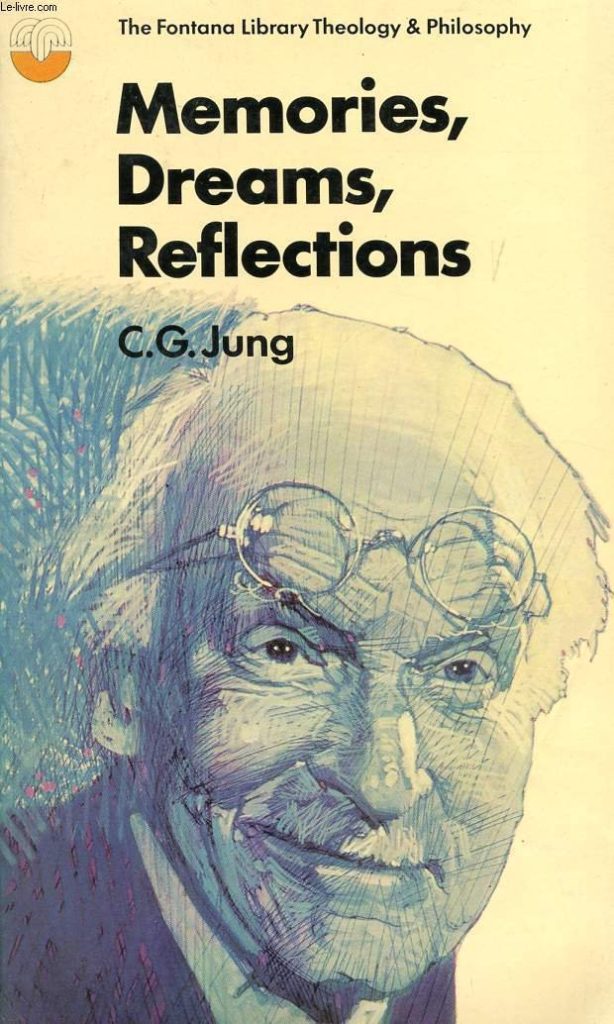

Scholars know this. Carl Jung spent a lifetime exploring those dreams and fears, which he called the unconscious. Linguists debate the origins of Homo’s speech. Archaeologists catalogue the craftsmanship wrought by those hands. But it was I who released the genie of that wild world when I lowered my foot into its clawed signature that autumn morning.

It is I, and it is you, and it happens to us all the time. Think of it as our birthright. Think of it as coming home.[15]

Like the hard drive on a computer, but far more powerfully, the human mind has been whirring away for hundreds of thousands of years. Mind is cumulative, a storehouse; it is memory that absolutely refuses to be cut off at the knees. When a limb is amputated, the lost hand or foot becomes a neurological ghost; the mind insists on sensing its presence. Likewise, the Paleolithic mind in each of us remains a neurological ghost, although the memory I speak of is even more tenacious than the shadow of a lost limb.[16] “Past upon past has been planted in you,” exhorts Rilke, “in order out of you, like a garden, to rise.”[17]

Consider those hands on cave walls, reaching through rock’s membrane; imagine the mind behind all this. The danger is that we fail to notice the huge and waiting consciousness that spans the octave of creation. Is this not what Charlie Kilangak (the puffin) invoked when he told me that bears hear us? Or the Bushmen who feel the approaching springbok? And what about the fellow who refused to throw away the fungus, a “rain’s thing”? Or Marie Meade relating the story of the Eskimo hunter and the loon eggs?

The disturbing part was Meade’s assurance: “It’s a true story!”

It is the truth of the First World, of the human yardstick up to the last one or two notches, when, in Mesopotamia and several other hot spots around the world, my ancestors lurched into the Second World.

Expounding on this First World, an Inuit woman put it this way: “In the very first times . . . both people and animals lived on the earth, but there was”—I imagine her turning and glancing at Rasmussen, her interlocutor—“no difference between them. . . . A person could become an animal and an animal could become a human being. There were wolves, bears, and foxes, but as soon as they turned into humans they were all the same. They may have had different habits, but all spoke the same tongue, lived in the same kind of house, and spoke and hunted in the same way. . . . Sometimes they were people and other times animals, and there was,” she emphasized, “no difference.”[18]

Put in the modern idiom, Nâlungiaq the Netsilik is describing totemism: symmetrical consciousness, shared perfectly between human people and what people of the First World call animal people. Which explains why the shaman Orpingalik whispered.

I have heard this consciousness affirmed repeatedly by Yup’ik Eskimos on the Alaska tundra. To put it starkly, for at least a hundred thousand years my forebears and yours spoke certain words in a whisper, knowing that a word “would suddenly become powerful, and what people wanted to happen could happen, and nobody,” added Nâlungiaq, “could explain how it was.”[19]

Nobody can explain it, unless we acknowledge that, in the First World, consciousness between mankind and the natural world, especially the animal world, was convergent. A natural world that was wild. Not domesticated, not tamed, not owned—absolutely wild.

How different from the consciousness of the Second World! Picture René Descartes in dressing gown and slippers seated comfortably before a fire, wrestling with the existential question that has troubled him for years: How do I know anything at all? Slowly, painstakingly, the parlor philosopher strips away all knowledge (“I resolved to doubt all things,” he effectively wrote), like peeling layers off an onion, till about him on the floor lie scattered the facts of a lifetime, discarded now as illusions. (It is a courageous act to disassemble one’s mind like that.) Just before tumbling headlong into madness, he finds what he is after. The simple yet perfect truth rings forth: “I think, therefore I am.” Here is the Word, the Logos upon which he will rebuild the modern mind.[20] Descartes has collapsed all knowledge and thought and being upon himself. With this bold declaration he has laid the cornerstone of modern philosophy.[21]

For years I have hunted for the crack-up of our symmetrical, convergent ancestral consciousness—the shattering of the flawless sheet of glass, the moment when the mind that thought in conversation with the earth collapsed into the mind that now observes the earth: mankind apart. Cogito, ergo sum distills it in purest, crystalline form, but it does not mark the beginning of the crackup, whose seismic rumblings go back to Aristotle and other Greek philosophers, to Christian theologians (see Augustine), to Bacon and Giordano Bruno.[22] Descartes merely brings these streams of thought to their logical, inevitable, and disastrous end point. Think of the solipsism, Cogito, ergo sum, as the essence of the ‟human exceptionalism” proposition that has achieved dominion everywhere on earth.

Socrates, Plato’s mentor, illustrates the point. We’re all more or less familiar with the Socratic method: teaching by questioning. But it is more radical than this; it is a clue to the beginning of the modern mind. The teacher would have his students recite truth and mystery, and perforce they would recite myth: the ancient thing, the unquestioned thing, the thing that never happened but just was, neither time-bound nor time-binding. Myth’s power came from the words themselves, from the telling, the repeating.

Now Socrates questioned it. “How do you know?” Over and over he sowed doubt. It dumbfounded them, his students. They had no response. He created an uproar in Athens.

How do I know anything at all? muses the philosopher, gazing into the embers of his fire. Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle had not journeyed far enough into Rilke’s “nightmare of knowing” for Descarte’s tastes.[23] “I resolved to assume that everything that ever entered into my mind was no more true than the illusions of my dreams,” he wrote; he would reject “as absolutely false everything as to which I could imagine the least ground of doubt.” ‟Like one who walks alone and in the twilight,” he resolved ‟to go so slowly and to use so much circumspection in all things that if my advance was but very small at least I guarded myself well from falling.”[24]

Good to go slowly and be circumspect—but it was too late. The fall had already happened, long before the Greeks. It is the fall from the First World that I refer to, Adam and Eve tumbling into agrarian consciousness and discovering the shame of their naked totemic selves. I am talking about the even older Mesopotamian epic wherein the wild man Enkidu is tricked out of animal kinship to join the demigod superman Gilgamesh.

“Then the eyes of both were opened,” it is said of Adam and Eve, “and they knew that they were naked; and they sewed fig leaves together and made loincloths for themselves.”[25] The ancient texts likewise say that Enkidu became “aware of himself” after being seduced by the temple “harlot” Shamhat, sent by Gilgamesh to domesticate him. “When he turned his attention to his animals, the gazelles saw Enkidu and darted off. The wild animals distanced themselves from his body.”[26]

What the Bible calls the fall of man obscures a deeper, more troubling fall: humanity setting its face against the wild things to make itself “master and possessor of nature,” as Descartes wrote.[27] The fall is the wild man Enkidu, “offspring of the mountains, who eats grasses with gazelles,” transforming into ’ᾰdāmâ—literally, arable, cultivable land.[28]

’Ādām (Adam) = farmer.[29] Except that the man we call Adam didn’t begin as ’ādām. The Yahwist author of the Hebrew creation story (considered older than the Elohist and Priestly versions) silently acknowledges that Adam originally knew a different consciousness—a different species of language, even, although what that was is obscure. The Gilgamesh narrative, possibly derived from older Semitic or Sumerian sources, is more revealing. With Darwin and archaeology and ethnology the answer becomes clearer: Adam’s first consciousness was wide open to the boundless, seething consciousness surrounding him, free of good and evil, which apparently were irrelevant. Like Enkidu, the biblical pre-’ādām spoke with the amassing harmony, the implicate order, that walked “at the time of the evening breeze.”[30]

“Not only does ’ādām cultivate ’ᾰdāmâ, he is fashioned by God out of the land he farms,” explains Theodore Hiebert in The Yahwist’s Landscape: “’ᾰdāmâ is the beginning and the end of human life. As the first human was derived from arable soil, so all humans are destined to return to it at death. . . . ’ādām is thus linked to ’ᾰdāmâ in two important respects: ’ᾰdāmâ is the stuff out of which ’ādām is made and is also the primary object of his labor.”[31]

Adam (’ᾰdāmâ)—what the novelist Daniel Quinn calls the Great Forgetting—is a colossal, mind-blowing exercise in forgetting the yardstick—our wildness.

“You are beautiful, Enkidu,” whisper the gods; “you are become” like one of us. “You are . . . like a god.”

Why do you gallop around the wilderness with the wild beasts?

Come, let me bring you into Uruk-Haven,

to the Holy Temple, the residence of [the gods] Anu and Ishtar.[32]

The words are given to the harlot Shamhat, yet they are the beckoning call of all sky gods wherever the ’ᾰdāmâ heresy prevails. (Witness the Mayan “Dawn of Life,” the Popol Vuh.)

And “the Lord God sent him forth from the garden of Eden, to till the ground from which he was [not] taken.” As if to seal Adam’s Great Forgetting of that First World of totemic origins, Yahweh placed “the cherubim and a sword flaming and turning to guard the way to the tree of life.”[33]

We have come a long way: from the hand reaching into the depths of the earth to touch the keepers of the game to the hand reaching skyward in the dome of the Sistine Chapel toward a hand not in the least totemic or chthonic but merely as Michelangelo depicts it: belonging to a man, nothing more. A tragic redundancy whose only creation was the cunning sin named ’ᾰdāmâ: domestication, a landscape “plotted and pieced—fold, fallow, and plough.”[34]

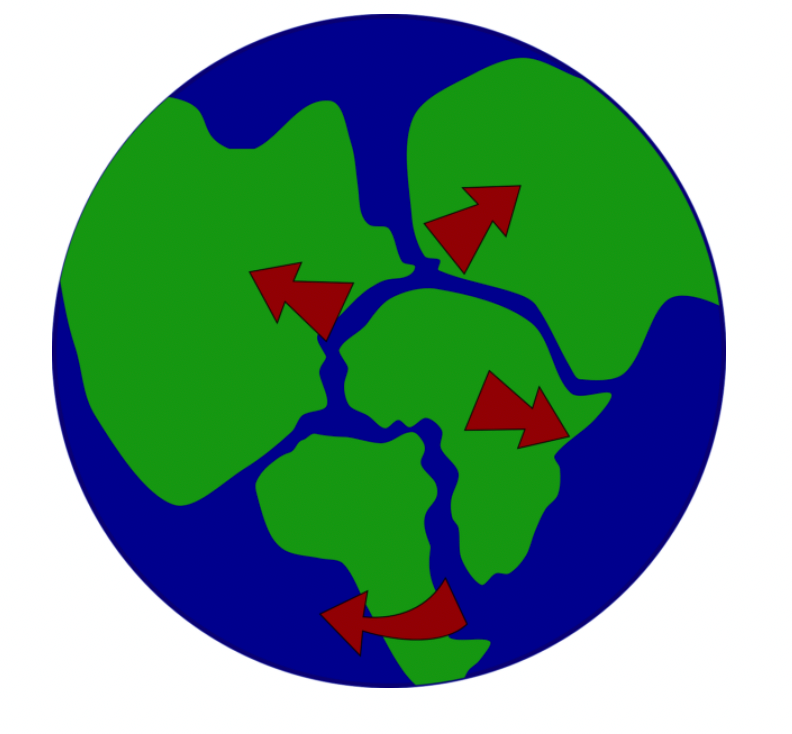

Imagine a universal consciousness of wildness. Think of it as a supercontinent of mind, a Pangaea of wildness. There are no sky gods in this commonwealth, no combat myth of good and evil. Reigning supreme are totemism (animal kinship and consciousness) and the gift (the knowledge, born of the womb and reaffirmed by totemism, that humankind is taken care of).

Imagine that in the Middle East a fault line forms deep within this consciousness.[35] A rift: a doubt. How do you know you’re taken care of? The consummate Socratic question.

Rilke revisits the doubt, “the heavy thing,” Mary Oliver calls it.[36] Rilke, the brooding solitary who gazed upon the womblike totemic place known to child and animal alike, interrogates the dark angel with flaming sword that bars his return to Paradise.[37] “Who has turned us around like this,” he asks, “so that / always, no matter what we do, we’re in the stance / of someone just departing,” departing “the Open / that lies so deep in an animal’s face”? He presses on. “Where we see Future it [the animal] sees Everything / and itself in Everything and healed forever.”[38]

The answer comes to him in “The Unfinished Elegy.”[39] Its name is Fear. Its signature is Doubt. It is the question that smashed the ancient totemic looking glass in The Epic of Gilgamesh: “You are beautiful, Enkidu, like a god. Why do you gallop around the wilderness with the wild beasts?”[40] The answer given to Rilke by the angel guarding the Open is equally devastating and uncannily similar to the words of the temptress: “When the child measured himself / against and distinguished himself from the You / unselfishly created over there.”[41]

Shamhat’s question, like that of Socrates and Descartes (and I confess, the question I implicitly drilled into my Eskimo seminarians), is the cold draft that “makes its way in through the cracks,”[42] the question that separates us from the You unselfishly created over there. The question, like the genie, that can never be coaxed back into the enchanted lamp.

Am I truly taken care of? Will the animal bosses yield their brethren to me? Will geese return? Will caribou herds return, and moose in the Kilbuck range, and salmon thronging the Kuskokwim, and coastal seals? I asked these questions of a Yup’ik Eskimo hunter. He answered squarely in the affirmative.

“Because I need them!” he exclaimed, as if nothing could be more obvious.[43]

The man’s answer is hilarious. Like Paul John telling the biologist that moose listen when we speak of them.

The cleft deepens. A new land mass forms, broken off from the mother continent and working at cross purposes to it. From Lascaux to Michelangelo and beyond, into our own time, the story of human consciousness is the tension between these two great continental plates slowly grinding past one another: wild (the gift) and domesticated (the controlled).

_________________

Footnotes

[1] Robert Bringhurst, “Zenophanes,” in The Beauty of the Weapons: Selected Poems, 1972–82 (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1982), 65–66.

[2] Charlie Kilangak Sr., Emmonak, AK, autumn 1994.

[3] As an aside, it´s interesting that the Gospel of Mary, an early second century account of Jesus found among Coptic manuscripts in the late 19th century, has the risen ‟savior” telling his disciple, Peter, ‟There is no such thing as sin,” by which Jesus meant so-called original sin: intrinsic, inherent guilt and shame. See Karen L. King, The Gospel of Mary of Magdala: Jesus and of the First Woman Apostle, 13.

[4] Nietzsche had strong feelings about Christianity´s doctrine of sin, calling it a ‟cancer germ” championed by St. Paul, chiefly as a means of control for the new religion he was inventing. See ‟The Antichrist,” 162, 97, 117, 132-133, 142, 143, 158-159, 260. In Beyond Good and Evil he (not altogether) facetiously protests, ‟We are most dishonorable towards our God: he is not permitted to sin,” 81.

G. K. Chesterton, who is said to have inspired C. H. Lewis to embrace Christianity, had a wholly different opinion on the subject. ‟The ancient masters of religion . . . began with the fact of sin—a fact as practical as potatoes. Whether or not man could be washed in miraculous waters, there was no doubt at any rate that he wanted washing” (Chesterton, Orthodoxy, 22).

[5] Rilke, “Eighth Elegy,” 47.

[6] William Blake, “A New Jerusalem,” in A Treasury of Great Poems: English and American, ed. Louis Untermeyer (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1942), 611.

[7] Job 1:1–3 (KJV).

[8] The following paragraphs are taken from Elizabeth Marshall Thomas, The Old Way: A Story of the First People (NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006), 314.

We should consider our cultural view of the Ju/wasi. We call them Bushmen because the bush is where we first encountered them. We call them hunter-gatherers because that is how they got their food. We tried to elevate matters a bit by renaming them San, but even though that name was coined by the Khoikhoi, not by Western people, it nevertheless involves the Bushmen’s poverty and our desire for rectitude, so this name, too, reflects our culture.

These same people, however, do not define themselves by the shrubbery or how they once ate or by their poverty. Instead, they define themselves by their sense of community. They call themselves the Clear People, the Worthwhile People, the People Who Have Left Their Weapons Somewhere Else, the Harmless People. Ju, as has been said, means “person” and /wa (also /’hoan) however hard to interpret, obviously does not refer to landscape, food gathering, or poverty. Instead, it reflects the way the people live together and relate to one another. And that is what really defines the Ju/wasi, not Western notions about the bush, or poverty, or our own moral rectitude, or food production.

[9] ‟And we indeed recognise in ourselves the image of God, that is, of the supreme Trinity, an image which, though it be not equal to God, or rather, though it be very far removed from Him—being neither co-eternal, nor, to say all in a word, consubstantial with Him—is yet nearer to Him in nature than any other of His works, and is destined to be yet restored, that it may bear a still closer resemblance” (Augustine, The City of God).

[10] Wilhelm H. I. Bleek and Lucy C. Lloyd, eds., Specimens of Bushmen Folklore (London: George Allen, 1911; reprint, Einsiedeln, Switzerland: Daimon Verlag, 2001), 335. Page references are to the 1911 edition.

[11] Knud Rasmussen, The Netsilik Eskimos: Social Life and Spiritual Culture, Report of the Fifth Thule Expedition, 1921–24: The Danish Expedition to Arctic North America in Charge of Knud Rasmussen, PhD, vol. 8, nos. 1–2 (Copenhagen: Gyldendalske Boghandel / Nordisk Forlag, 1931), 14.

[12] Bleek and Lloyd, Specimens, XV, emphasis hers.

[13] Eiseley, The Immense Journey (New York: Vintage Books, 1946).

[14] Oliver, “Wild Geese,” in Owls and Other Fantasies: Poems and Essays (Boston: Beacon Press, 2003), 1.

[15] See Andrew Saltarelli, Leaving Home (Malone, NY: K-Selected Books, 2023).

[16] “The nineteenth century, in the efforts of men like Hughlings Jackson, came to see the brain as an organ whose primary parts had been laid down successively in evolutionary time, a little like the fossil strata in the earth itself. The centers of conscious thought were the last superficial deposit on the surface of a more ancient and instinctive brain. As the roots of our phylogenetic tree pierce deep into earth’s past, so our human consciousness is similarly embedded in, and in part constructed of, pathways which were laid down before man in his present form existed. To acknowledge this fact is still to comprehend as little of the brain’s true secrets as an individual might understand of the dawning of his own consciousness from a single egg cell.” Loren Eiseley, The Invisible Pyramid (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1970), 21–22.

[17] Rilke, “Singer Sings before Child of Princes,” 171.

[18] Rasmussen, Netsilik Eskimos, 208.

[19] Rasmussen, Netsilik Eskimos, 208.

[20] René Descartes, Discourse on the Method and Meditations on First Philosophy, ed. David Weissman (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1996), 12–13, 15, 21–22, 58–59, 64, 66, 70, 100.

[21] It has been pointed out that Augustine to a degree anticipated Descartes´s ‟cogito, ergo sum” in the following passage from The City of God: ‟I am most certain that I am, and that I know and delight in this. In respect of these truths, I am not at all afraid of the arguments of the [Greek] Academicians, who say, What if you are deceived? For if I am deceived, I am. For he who is not, cannot be deceived; and if I am deceived, by this same token I am. And since I am if I am deceived, how am I deceived in believing that I am? for it is certain that I am if I am deceived. Since, therefore, I, the person deceived, should be, even if I were deceived, certainly I am not deceived in this knowledge that I am. And, consequently, neither am I deceived in knowing that I know. For, as I know that I am, so I know this also, that I know.”

[22] Giordano Bruno, The Expulsion of the Triumphant Beast.

[23] Rilke, “The Tenth Elegy,” in Duino Elegies, trans. Snow, 59.

[24] Descartes, Discourse, 21, 12.

[25] Genesis 3:7 (New Revised Standard Version).

[26] The Epic of Gilgamesh, trans. Maureen Gallery Kovacs (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1985), 8–10.

[27] Descartes, Discourse, 38.

[28] Epic of Gilgamesh, 8; Hiebert, Yahwist’s Landscape, 34–35, 38–40, 141.

[29] Hiebert, Yahwist’s Landscape, 141. An alternative spelling to ’ādām is hā’ādām.

[30] Genesis 3:8 (New Revised Standard Version).

[31] Hiebert, Yahwist’s Landscape, 35.

[32] Epic of Gilgamesh, 9.

[33] Genesis 3:23–24 (New Revised Standard Version).

[34] Gerard Manley Hopkins, “Pied Beauty,” in A Treasury of Great Poems: English and American, ed. Louis Untermeyer (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1942), 978.

[35] The rift was not confined to the Middle East, though it may have been more cataclysmic and portentous here than elsewhere. Out of it emerged Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

[36] Oliver, “Aerialists,” in Twelve Moons, 44.

[37] See Rilke, Poems from the Book of Hours, trans. Babette Deutsche (New Directions 1941).

[38] Rilke, “Eighth Elegy,” trans. Snow, 51, 47, 49.

[39] Rilke, “Unfinished Elegy,” in The Unknown Rilke: Expanded Edition, Selected Poems, trans. Franz Wright (Oberlin, OH: FIELD Translation Series 17, Oberlin College Press, 1990), 155–159.

[40] Epic of Gilgamesh, 9.

[41] Rilke, “Unfinished Elegy,” 158.

[42] Rilke, “Unfinished Elegy,” 157.

[43] Oscar Active, Bethel, AK, April 12, 1996.