The Implicate Order

The skeleton key to the universe

Calvin Luther Martin, PhD

November 1, 2024

Prof. Arthur Schopenhauer

Descartes

The alert and muscular Adam you see above you is Renaissance man, the man becoming the intellectual superman. Rational, awakened mankind.

Nietzsche’s crack-up in a chance encounter with Equus, when the subject-object boundary came crashing down.

You see everything through their eyes—their joy, their necessity.

His intellectual heir turns up in starched collar and round glasses, peering back at us from daguerreotypes and black-and-white photographs, as the nineteenth- and twentieth-century superman of science.

(In this case, Max Planck.)

The clock, above, belongs to Jehovah. This biblical clock exists in something separate from time, called heaven and earth in the biblical scheme of things. The clock and heaven & earth serve the purposes of the Hebrew god whose purposes are folded into Christianity’s purposes. Biblical time and space have nothing to do with the physicists’ unified space-time, except that both are part of the “will to power” agenda. (Thanks to Neogard for the image.)

“No, Prof. Hegel, we don’t all think in names. Only the man who sees himself as subject, contemplating a world he imagines to be the object outside him, can think in names.”

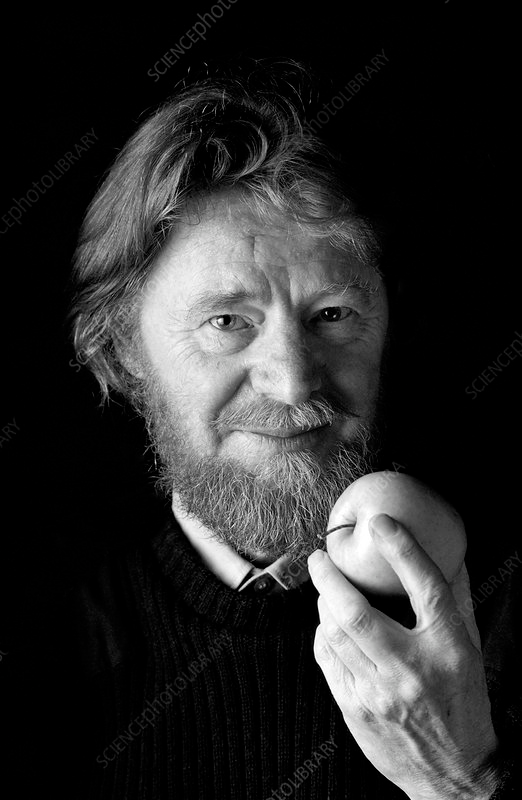

John Bell,

reportedly nominated for a Nobel Prize in physics—but he died during the deliberations.

“How an old man in flannel shirt and Levi’s could casually reveal an intimate acquaintance with nonlocality is a matter of concern.”

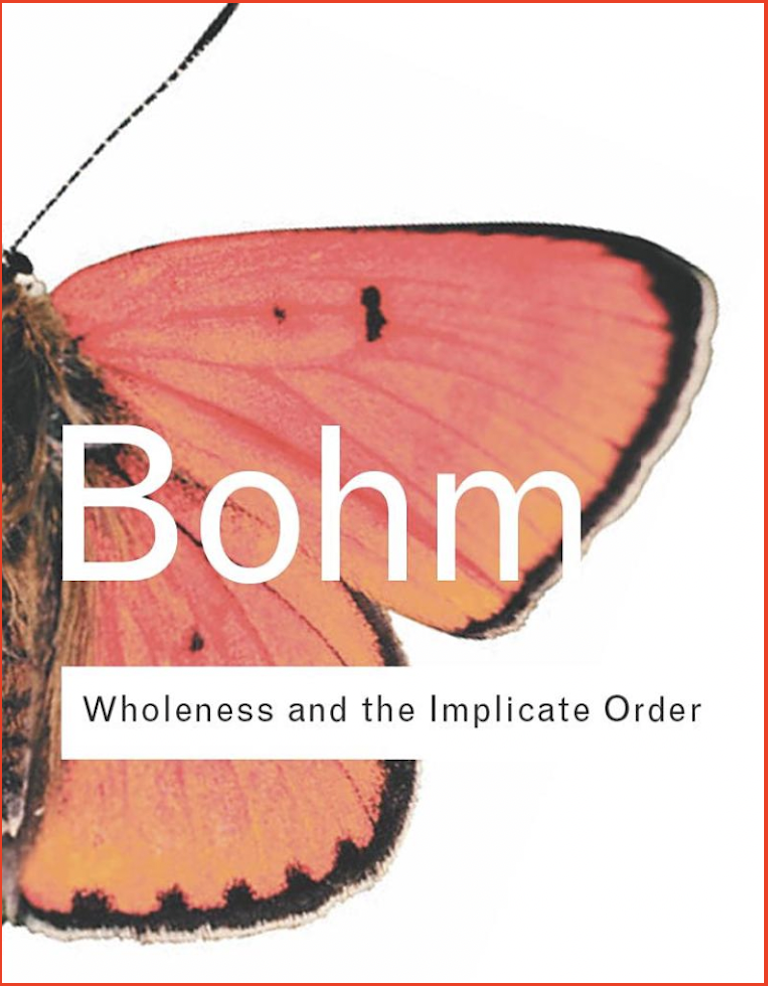

Prof. David Bohm

Published 1980

Prof. Basil Hiley

Prof. Erwin Schrödinger,

Nobel laureate in physics

Physics’s Crystal Ball

The business of physics always has been the business of measurement and, following on this, predicting outcomes for practical applications. Praxis is the operative word.

Max Planck as the Superman

Conjuring up theories and experiments with practical and reasonably predictable outcomes

As a child one gets lost there in the quiet, only to be jostled back.

Isaac Newton

Prof. Eugene Wigner,

Nobel laureate in physics

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Plotinus, as I like to imagine he looked.

J. Robert Oppenheimer

“We have killed God—you and I! We are all his murderers!”

Prof. David Bohm

The absolute is dead! Thus spoke Bohm. If science slew the absoluteness of God, Q shattered the absoluteness of science.

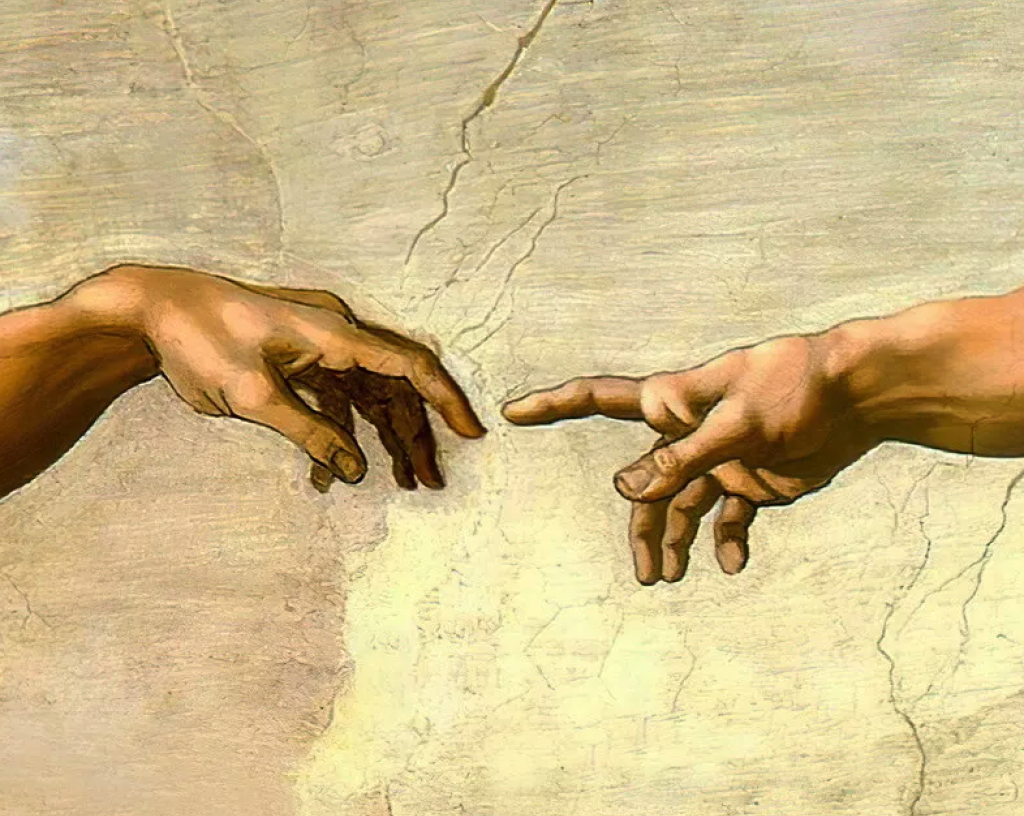

Stand on the marble pavement of the Sistine Chapel and look up. Hovering above you, Jehovah reaches through the firmament to touch Adam’s forefinger and bestow divine consciousness.

Except that there is no such thing as divine consciousness. It’s fairy dust. Michelangelo knew this, as did every other educated person at the time. What you’re looking at is an erotic celebration of Renaissance rationalism. If the deity on the ceiling spoke French, and if there were a speech bubble above his head, it would read “Sors de l’enfance, ami, réveille-toi!” Wake up, my friend, and leave childish things behind!

The phrase is Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s (lifted from the Apostle Paul).[1] Arthur Schopenhauer used it as the epigraph to his magnum opus, The World as Will and Representation (1818, expanded 1844). “ ‘The world is my representation,’ ” it begins:

This is a truth valid with reference to every living and knowing being, although man alone can bring it into reflective, abstract consciousness. If he really does so, philosophical discernment has dawned on him. It then becomes clear and certain to him that he does not know a sun and an earth, but only an eye that sees a sun, a hand that feels an earth; that the world around him is there only as representation, in other words, only in reference to another thing, namely that which represents, and this is himself. If any truth can be expressed a priori, it is this; for it is the statement of that form of all possible and conceivable experience, a form that is more general than all others, than time, space, and causality, for all these presuppose it.

With Descartes’s res extensa and res cogitans in mind, Schopenhauer emphasizes that

while each of these forms . . . is valid only for a particular class of representations, the division into object and subject . . . is the common form of all those classes; it is that form under which alone any representation, of whatever kind it be, abstract or intuitive, pure or empirical, is generally possible and conceivable. Therefore, no truth is more certain, more independent of all others, and less in need of proof than this, namely that everything that exists for knowledge, and hence the whole of this world, is only object in relation to the subject, perception of the perceiver, in a word, representation. Naturally this holds good of the present as well as of the past and future, of what is remotest as well as of what is nearest; for it holds good of time and space themselves, in which alone all these distinctions arise. Everything that in any way belongs and can belong to the world is inevitably associated with this being-conditioned by the subject, and it exists only for the subject. The world is representation.[2]

Schopenhauer doesn’t mince words. God stretching forth his creator’s hand to Adam on the ceiling above you is a magisterial rendering of Schopenhauer’s subject-object dichotomy, the aberrant state of consciousness that spawned the Neolithic (as I have pointed out elsewhere) and that was well on the way to full flowering in Western Europe by Michelangelo’s time.[3]

It’s important to understand that the alert and muscular Adam you see above you is Renaissance man, the man becoming the intellectual superman, not the primitive specimens of humanity destined for the dustbin of history in dark Africa or the recently encountered New World. Secondly, the mural ostensibly renders Jehovah as subject and Adam as object. In fact it is the reverse; the real subject is man—rational, awakened mankind. And the real object is the phenomenal world (represented by the heavenly pantheon) that the enlightened Renaissance man witnesses and represents in language, art, technology, philosophy, religion, science, mathematics—in everything awakened man touches and sees and contemplates. Schopenhauer got it right.

Even so, Michelangelo has given us a glimpse of an impending train wreck, although it’s unlikely he sensed this. By the sixteenth century the hand of God was little more than an ad hoc, Planck’s constant in a rapidly unfolding equation in providential mathematics. Even as the master’s paint was drying, Europe’s intelligentsia were leaving the ecclesiastical childish things behind and hurtling toward Descartes’s res extensa (things outside of us) and res cogitans (things we think), Newton’s laws of motion, and Schopenhauer’s subject-object dogma, culminating in Nietzsche’s spectacular crack-up in a chance encounter with Equus, when the subject-object boundary came crashing down like the biblical walls of Jericho.

Adam’s Wall, Nietzsche discovered, was not invulnerable. In this terrifying moment he unwittingly made contact with the supercontinent of participatory consciousness known to Paul John—who “knew” as he was “known.” Plato, Aristotle, Augustine, Aquinas, Descartes, Schopenhauer, Hegel, Kant, the Bible: none of them had warned the philosopher that the subject-object separation is fake. As with Thoreau blasted by the silently unfolding presence of Katahdin, nothing had prepared him for the trauma of the human-Equus boundary vanishing.

“Pas malade!” exclaims Nietzsche to the psychiatrist, Dr. Turina, who was fetched to calm him down. I’m not sick! I said more or less the same to my psychiatrist after my mind, too, lost its grip on boundaries. Somehow I knew that my darkness—Thoreau’s Chaos and Old Night nails it—was a new beginning: contact with something I thought had been left behind.[4]

It wasn’t. Witness Loren Eiseley’s fictional alter ego Albert Dreyer, the zoologist with the strangely-gloved hand who “journeyed farther into the Country of Terror than any of us would ever go, God willing, and emerge alive.” Or Mary Oliver’s hymn to spring peepers. “You think it will never happen again,” she begins, “Then, one night in April, / the tribes wake trilling.” Like Dreyer, Oliver becomes one of them. “You see everything / through their eyes, / their joy, their necessity.” [5]

Carl Jung warned of this Chaos and Old Night, perhaps remembering his experience with the First World of consciousness (“primitive psychology,” he called it) in west Africa. “The primitive,” he confessed, “was a danger to me. . . . Any attempt to go deeper into it touched every possible sore spot in my own psychology.”[6]

It’s not the primitive that’s dangerous; the danger is the collapse of the subject-object proposition, the heresy that launched civilization and without which, by any logical measure, it collapses. At least it should. Stripped of this garment, civilization exposes itself as a naked act of aggression.

It has not collapsed. Nor will it. For its magic is to make the irrational, rational. Civilization lurches onward more and more brazenly as a zombie creation of human imagination; an “adventure to be endured with the politest helplessness,” writes Stevens.

The assassin’s scene. Evil in evil is

Comparative. The assassin discloses himself,

The force that destroys us is disclosed, within

This maximum, an adventure to be endured

With the politest helplessness. . . .

One feels its action moving in the blood.[7]

Once the arrow we call civilization left the bow—once sky gods were cobbled together from the confiscated or purloined powers of chthonic and wildlife sources, once the dial had been set for systematic, relentless animal bondage and agriculture—there could be no turning back by the time of the Renaissance Adam, convinced that “the world is my representation.” His intellectual heir turns up in starched collar and round glasses, peering back at us from daguerreotypes and black-and-white photographs, as the nineteenth- and twentieth-century superman of science.

Superman controls all knowledge. He is not you or me. He is a logical lunatic.[8] We must not make a scene; we must calmly accept this, just as Paul John, Harry Wilde, Steven White, and Antone Anvil were obliged to accept the authority of the “managers of the ecology” who, Elizabeth Costello acidly explains to her audience, “understand the greater dance, [and] therefore . . . can decide how many trout may be fished or how many jaguar may be trapped before the stability of the dance is upset.”[9]

Randy Kacyon’s message to the Yup’ik advisory committee was effectively “Gentlemen, all wild things are our representation. Moose, for instance, are res extensa, ‘extended substance,’ controlled by mankind’s sovereign power of res cogitans, ‘thinking things.’ ”[10] Philosophical discernment had dawned on him.

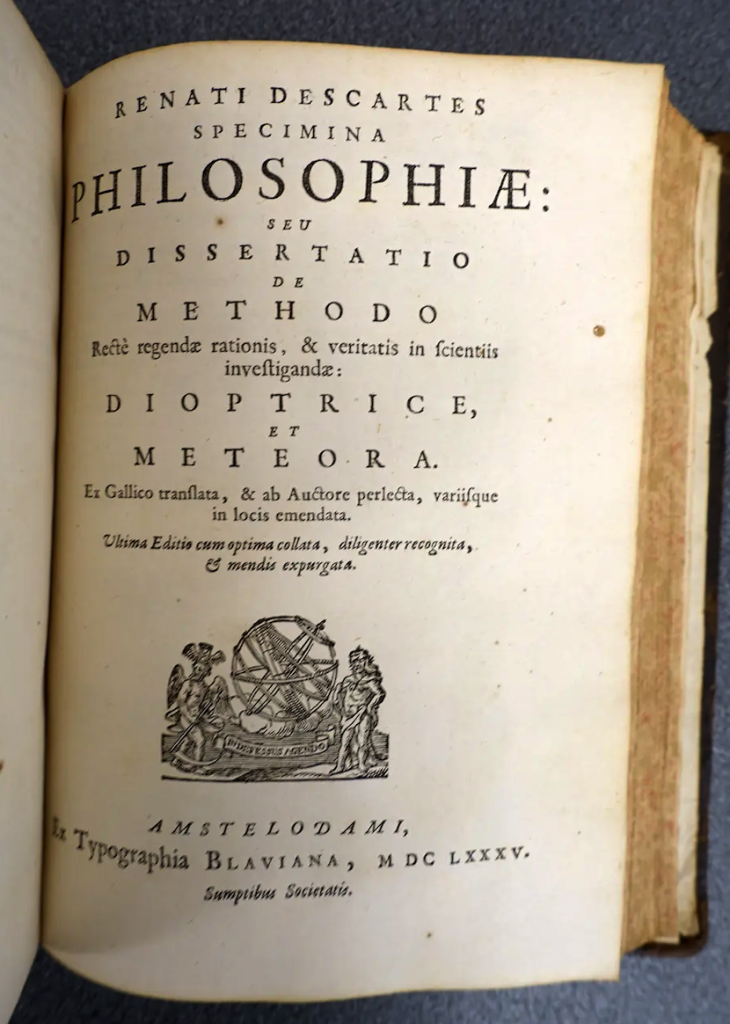

Descartes, who bestowed res extensa and res cogitans upon us, along with “Cogito, ergo sum,” was dazzled by the brave new world offered by physics, as Enkidu was by the brave new world between Shamhat’s heavenly thighs and her gospel of good news from Gilgamesh. “So soon as I had acquired some general notions concerning Physics,” Descartes enthuses in Discourse on the Method of Rightly Conducting One’s Reason and of Seeking Truth in the Sciences (1637), “they caused me to see that it is possible to . . . find a practical philosophy by means of which, knowing the force and the action of fire, water, air, the stars, heavens and all other bodies that environ us, as distinctly as we know the different crafts of our artisans, we can in the same way employ [read: “harness”] them in all those uses to which they are adapted, and thus render ourselves the masters and possessors of nature.”[11] [Use Bacon´s New Atlantis as an illustration.]

He was right. In the centuries following, physicists proved themselves the supreme “masters and possessors of nature.” [Insert Goethe & Carlyle?] Like Saint Peter, they hold the keys to the heavens. Their twisty, complicated formulae chalked on university blackboards (reminiscent of Lascaux and Chauvet) contain the code to unlocking the cosmic “what is” (E = mc2 gave us the Bomb), from the explosive birth of space-time (Einstein proved the two are inseparable) to its annihilation in an infinitely inflationary or infinitely collapsed universe. Either way what’s left is a smooth, symmetrical void—presumably the state of affairs from which the Big Bang created space-time, billions of years before the Hebrew deity of space-time instructed agrarian man, Adam, to insert the wild things into space-time by giving them a name. [See Carlyle on the alphabet of creation.]

Confiscating the being and becoming of wild things through naming them was a prerequisite to rendering farming palatable and practicable. [See Bacon on the ‟real” names that control creatures. See Socrates on names?] (See Job with his fourteen thousand sheep, six thousand camels, two thousand oxen, and one thousand donkeys.[12]) In Hegel’s words, “The first act whereby Adam constituted his rule over the animals was that he gave them names; that is, he annihilated them as beings.”[13] “The name,” Hegel continues, “is thus the thing so far as it exists and counts in the ideational realm. . . . Given the name lion, we need neither the actual vision of the animal nor its image, even: the name, alone, if we understand it, is the unimaged simple representation. We think in names.”[14]

Not quite true, Professor Hegel. Only the man who sees himself as subject, contemplating a world he imagines to be the object outside him, can think in names—names that codify nothing more than a space-time geometry of enfolding and unfolding events like “the little walker” and tuntuvak.

What if we can reach back before the naming took place? Where the wild things, like the little walker and a rain’s thing, are? What if we can access the axis of reality where a python is an elephant, antedating or simply having no use for Adam’s Wall, as with the Netsilik, Bushmen, Apache, and the Yup’iks I lived with on the Alaska tundra?

When we do reach this state, we find a human-animal discourse remarkably congruent with quantum mechanical principles, as pointed out in the last lecture; a dialogue with features—dare I call them rules?—remarkably harmonious with the pre- or non-space-time processes that govern the universe. To a biologist, Paul John’s reference to listening moose may sound like fantasy. To an anthropologist, it may sound like “fetishized utility.”[15] To a physicist, on the other hand, the old man from Toksook Bay was clearly referencing nonlocality, what Einstein dismissed as “spooky action at a distance.”[16] Einstein thought that nothing could travel faster than the speed of light. John Bell, building on David Bohm’s work, proved otherwise: subatomic information (if we can call it this) can travel instantaneously—though we’re not sure it’s “traveling,” as we shall see below.

One might object that physicists are referencing subatomic matter, whereas Yup’iks are referencing moose, caribou, bears, seals, or walrus. The difference in scale is a deal-breaker, argued Nobel laureate Eugene Wigner in debate with John Archibald Wheeler.[17]

Setting Wigner’s objection aside for the moment, let me begin by admonishing academics to remove their Cartesian or Marxist filters (what Marshall Sahlins derided as “the business outlook”) and recognize what’s staring us in the face.[18] If what transpired in that room sounds like nonlocality, behaves like nonlocality, and quacks like nonlocality, then, by golly, it’s nonlocality. How an old man in flannel shirt and Levi’s, with zero formal knowledge of quantum mechanical principles, could casually reveal an intimate acquaintance with “spooky action at a distance” is a matter of concern. It forces scholars to step back and reassess our entire epistemological enterprise.

Nonlocality is exactly what it says it is. Before diving into it, we first need to become familiar with the work of David Bohm, for it was Bohm who inspired John Bell to prove the existence of nonlocality in his 1964 theorem.

David Bohm was born and raised in Pennsylvania, earned his undergraduate degree at Penn State, did a year of graduate physics at Caltech, then transferred to UC Berkeley, where he earned his PhD under Robert Oppenheimer. Bohm was a genius. It’s said his doctoral thesis was instantly classified as top secret by Oppenheimer, who at this point was the chief physicist for the Manhattan Project. As an assistant professor at Princeton, Bohm, who had flirted with communism as a graduate student, ran afoul of McCarthyism. Princeton did not renew his contract, despite Einstein’s protests.

The self-confident young man from Wilkes-Barre spent the rest of his career challenging and refining quantum mechanics, to the annoyance of Oppenheimer and many of the theoretical physicists and mathematicians Oppenheimer was now collecting at the Institute for Advanced Study (in Princeton, New Jersey, incidentally). The institute crowd ostracized him, and Bohm couldn’t land a respectable academic position in America. Tossed out of Princeton University, he joined the faculty of the University of São Paulo; after several years he moved to an Israeli institute, then to a research position at Bristol University in the UK, and finally landed a professorship in theoretical physics at the University of London, where he stayed for the rest of his life. His treatment by academia, our government, and many in the physics fraternity is one of the more disturbing stories in the history of science.

This is the maverick who endeavored to explain the strange process of being and becoming—enfolding and unfolding—that Paul John somehow knew, though the old man couldn’t have done the math. (Nor could many scientists, it turned out.)

Bohm came to recognize the phenomenon, almost reverentially, as an uncanny energy-movement that ramifies through everything and links everything in non-space-time. He called it the implicate order. Wheeler, struggling to bring the issue into focus, called it “a new feature of nature, an elementary quantum phenomenon,” which is frustratingly “non-localizable” and “above all . . . untouchable, impenetrable, [and] impalpable.” “A mysterious new entrant on the stage of physics,” he marveled. “For all we know, it may someday turn out to be the fundamental building unit of all that is, more basic even than particles or fields of force or space and time themselves. But that is an issue for the future.”[19]

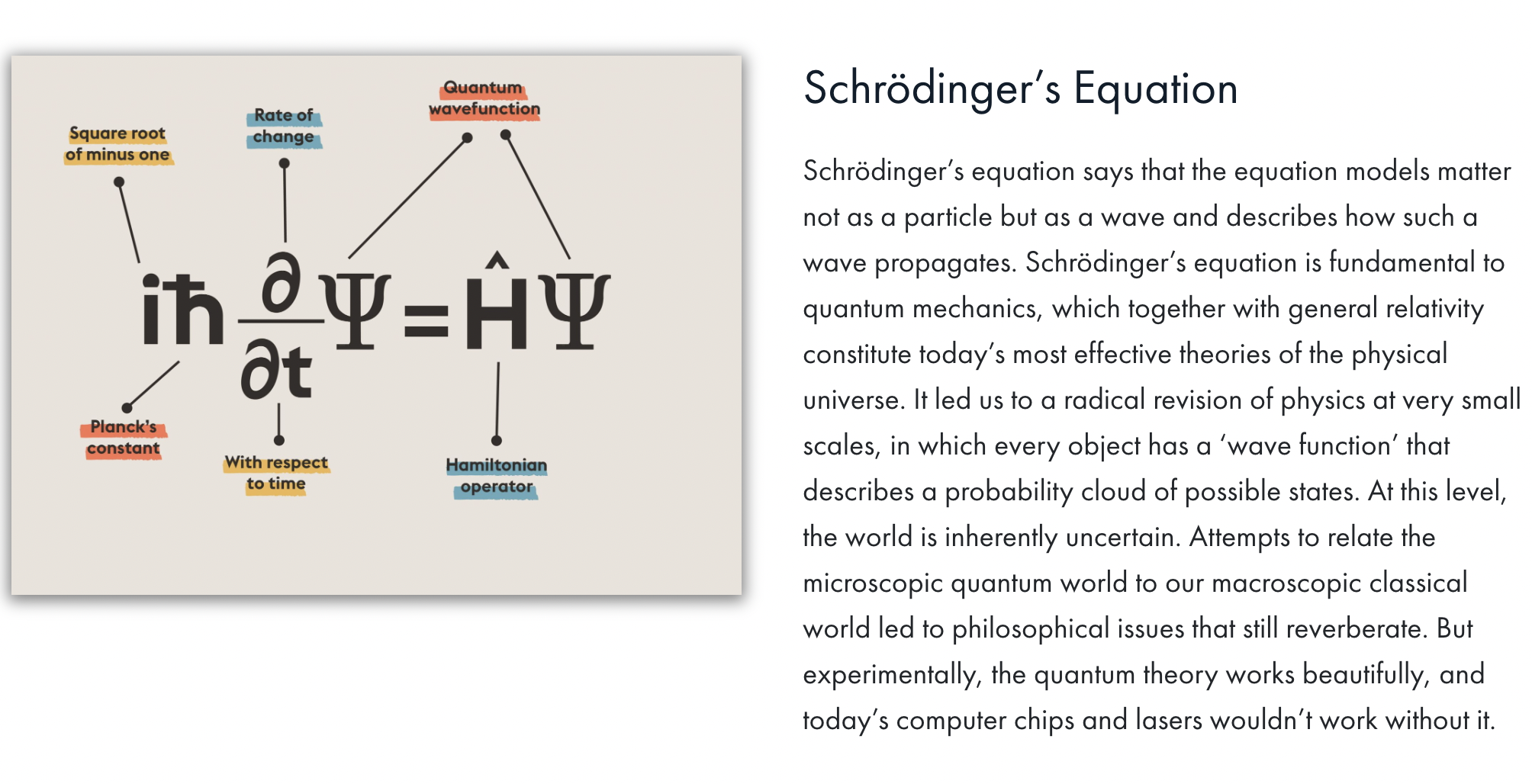

That future is still unfolding. This much is clear: even if we think we have smashed it to infinitesimally small bits, as in a linear accelerator, the elementary quantum phenomenon is not and never will be a building block—a concept that has done incalculable harm to our reasoning. There is a different process in play, argued Bohm and his colleague B. J. Hiley—a deeper, nonintuitive, nonmechanical process that eludes classical Newtonian physics, even when subjected to ingenious mathematical interrogation, as with Schrödinger’s equation (using partial differentials). We are better served, ventured Bohm, to view it as a stream, whose implicate ways are revealed in explicate manifestations as riffles, standing waves, and vortices. He called it “undivided wholeness in flowing movement.”[20]

On this stream, one may see an ever-changing pattern of vortices, ripples, waves, splashes, etc., which evidently have no independent existence as such. Rather, they are abstracted from the flowing movement, arising and vanishing in the total process of the flow. Such transitory subsistence as may be possessed by these abstracted forms implies only a relative independence or autonomy of behaviour, rather than absolutely independent existence as ultimate substances.[21]

At the core of this cosmic ensemble is an amassing, harmonious movement—“holomovement,” Bohm called it—an all-encompassing energy-momentum manifold within which space-time is an epiphenomenon.[22] One wonders if Erwin Schrödinger was thinking along the same lines when he cautioned against a literal interpretation of Schopenhauer’s declaration that “the world extended in space and time is but our representation”: “To say . . . that the becoming of the world is reflected in a conscious mind is but a cliché, a phrase, a metaphor that has become familiar to us. The world is given but once. Nothing is reflected. The original and the mirror-image are identical.”[23]

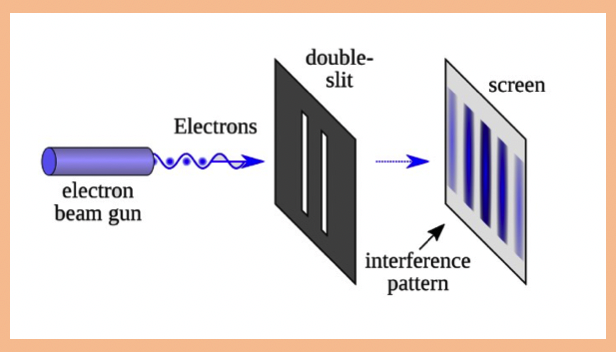

Much happened in the century between Schrödinger and Schopenhauer. Einstein’s special and general relativity, for one. Quantum mechanics, for another. Space-time and the nature of subatomic matter were now under intense scrutiny. It soon became obvious that the mere procedure of measuring subatomic particles compromised the outcome. Witness the double-slit experiment, diagrammed in the margin. (Wheeler calls it the split-beam experiment.[24])

When you don’t measure the trajectory of electrons fired from a photon (electron) gun through a double-apertured screen, they behave like particles. When you do measure their trajectory, they behave like waves.

Somehow the observer and his apparatus are being incorporated into the “being and becoming” of the particles, or waves, being observed. It’s impossible to disentangle / detach / emancipate / extricate / untie / set apart / tell apart / sort out / demarcate / severalize / disengage / separate / distinguish / discriminate / figure out / identify / pinpoint / differentiate / specify “observer” and “observed” under these conditions. (Yes, I have flogged the point to death. Yes, just as Rabelais would have done. Because ten thousand years of dichotomous “subject-object” thought / language / speech / reasoning / logic / physics / metaphysics / mathematics / theology / religion / philosophy / literature / economics / history / science / agriculture / animal domestication—and let’s throw in wildlife management—by Adam and his heirs, including Alaska state biologist Randy Kacyon, is a helluva tough habit to break.[25] The anthropologist Eric Wolf is said to have remarked that “the major force in world history is sheer dumbness.” I submit that the subject-object dichotomy tops the list.[26] Except that it wasn’t dumbness so much as the “will to power.” More on this later.)

Measurement is thought to collapse the wave function (see my discussion of superposition in Lecture 6)—a conjectured, probabilistic matrix or medium or (let me call it) symphony within which subatomic particles perform and manifest themselves.[27] Once the symphony collapses—again, like turning off the music in a game of musical chairs—particles are captured in a posture (occupying the chair, in the analogy of musical chairs) called forth by the parameters of the measuring apparatus—which, I have argued along with David Z. Albert, can include language.[28] (Note that different measurements using different apparatuses on the same particles can change the seemingly immutable characteristics of these same particles.)

By mid-century, when David Bohm joined the conversation, quantum mechanics was a battleground where tempers ran hot, name-calling was not uncommon, and further experiments revealed yet more ballooning weirdness. At this point many physicists excused themselves from debates that seemed more metaphysics than physics, and stuck with the equations, measurement protocols, and probabilistic outcomes served up before the field went off the rails with notions like nonlocality, participation (of observer in what is being observed), and nonseparability (of observer from observed). If nonlocality and nonseparability truly represent reality, argued many, including Stephen Hawking, then to hell with true reality, since it has no practical value and, worse, undermines the raison d’être of physics. The business of physics always has been the business of measurement and, following on this, predicting outcomes for practical applications.[29] Praxis is the operative word. “All I’m concerned with is that the theory should predict the results of measurements,” snapped Hawking.[30]

With this, mainstream physics pulled the plug on spooky reality and went back to conjuring up theories and experiments with practical and reasonably predictable outcomes, where the superman was once more in charge.

We’re back at square one, in a room where an old Eskimo hunter is making a fool of himself about moose in front of a squad of scientists brainwashed by praxis.

Who do we believe? The guys with the Fish & Game patches on their crisp green uniforms, or the guy in the faded flannel shirt? Who would Thoreau or Eiseley believe? Or Jung, after his conversation with Ochwiay Biano (“Mountain Lake,” in English), the Taos Pueblo wisdom keeper? Or Nietzsche, after they managed to pry his arms from the neck of Equus? Or Jesus of Nazareth, after what transpired in the Judaean wilderness? Or Mary Oliver, after composing “Pink Moon—The Pond”? Or Rilke, after the pure genius of the “Eighth Elegy”?

With all its eyes the animal world

beholds the Open. Only our eyes

are as if inverted and set all around it

like traps at its portals to freedom.

What’s outside we only know from the animal’s

countenance; for almost from the first we take a child

and twist him round and force him to gaze

backwards and take in structure, not the Open

that lies so deep in an animal’s face.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

We, though: never, not for a single day, do we

have that pure space ahead of us into which flowers

endlessly open. What we have is World

and always World and never Nowhere-Without-Not:

that pure unguarded element one breathes

and knows endlessly and never craves. As a child

one gets lost there in the quiet, only to be

jostled back.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Always turned so fervently toward creation,

we see only the reflection of the Open,

which our own presence darkens. Or sometimes

a mute animal looks up and stares straight through us.

That’s what destiny is: being opposite

and nothing else but that and always opposite.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

And yet, upon that warm, alert animal

is the weight and care of an enormous sadness.

For what sometimes overwhelms us always

clings to it, too—a kind of memory that tells us

that what we’re now striving for was once

nearer and truer and attached to us

with infinite tenderness. Here all is distance,

there it was breath. After the first home

the second one seems draughty and strangely sexed.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

And we: Spectators, always, everywhere,

looking at, never out of, everything!

It overfills us. We arrange it. It falls apart.

We rearrange it, and fall apart ourselves.Who has turned us around like this, so that

always, no matter what we do, we’re in the stance

of someone just departing?[31]

These are fair questions, mine and Rilke’s. Notice that I direct my question, each time, to someone who stood in the presence of wild things.

“Sors de l’enfance, ami, réveille-toi!”—Wake up, my friend!—and leave behind your childlike faith in the superman who believes that “the world is my representation through mathematics.” Physics does not hold the copyright to reality. The Greeks called this hubris.

The problem lies with the measuring apparatus, mathematics. Physicists fail to grasp something philosophers have known for centuries: a question is a statement. The questions asked by mathematics of the macro- and microcosmos are in fact statements in a numerically based language—“the most autonomous language that man has ever devised”—loaded with a priori epistemological and ontological assumptions.[32] “Everything cannot be so easily grasped and conveyed as we are generally led to believe,” cautions Rilke. “Most events are unconveyable and come to pass in a space that no word has ever penetrated.”[33] Nor has mathematics ever penetrated this space.

Meanwhile, reality at the human level is squarely Newtonian: deterministic, continuous, and local in space-time, and thus subject to the dynamic equations of motion. Thus saith physics, the Lord of Hosts (as witness Wigner in debate with Wheeler). Indeed, there is no better checklist for sanity. Anyone who fails or refuses to sign the Newtonian articles of faith is either a huckster, a screwball, or schizophrenic. Or possibly primitive, savage, and obviously a pagan, although we don’t use these impolite words anymore. “People of anthropological interest” is more acceptable. Like Paul John, Rasmussen’s Netsilik, Biesele’s Bushmen, and Basso’s Apaches.

Like language, mathematics is based on symbols and codes and can be massaged. It’s not immutable, nor is it real. Like language, it is representational and quite possibly metaphorical. Its canonical signs and operations—equal (=), addition (+), subtraction (–), multiplication (x), and division (÷)—are predicated on principles of logic and belief and rationality which Alfred Lord Whitehead and Bertrand Russell refer to as “undefined ideas and . . . undemonstrated propositions”: “primitive ideas and primitive propositions, respectively.”a

In mathematics, the greatest degree of self-evidence is usually not to be found quite at the beginning [owing to the primitive ideas and primitive propositions that are taken on faith: CLM], but at some later point; hence the early deductions, until they reach this point, give reasons, rather, for believing the premises because true consequences follow from them, than for believing the consequences because they follow from the premises.b

The towering structure built on these primitive ideas and propositions of logic doesn’t hold up under certain conditions, as demonstrated by the double-slit experiment. When this happens, physics resorts to a fudge factor called a constant or, when this fails, invokes probability. When these fail to convince, there are those like the late Hugh Everett III, who in 1957 postulated that measurements of (what appears to be) matter in fact result in the creation of parallel, noncommunicating physical worlds in which all the possible outcomes exist simultaneously—a courageous if not extravagant attempt (summarily dismissed by Niels Bohr, incidentally) to save classical linear equations of motion.[34]

With this in mind, note that in 1925, using the calculus of partial differentials, Erwin Schrödinger provided a mechanistic explanation for the wave function phenomena in quantum events. The Schrödinger equation, as it came to be known, won him the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1933. The only problem with the equation and its subsequent permutations is that the collapse of the wave function(s), the phenomenon that lies at the basis of quantum events, is not mechanical. “This means that the term ‘quantum mechanics’ is very much of a misnomer,” pointed out Bohm, the iconoclast. “It should . . . be called ‘quantum nonmechanics.’ ”[35]

Being nonmechanical means, by definition, that the collapse of the wave function is not explainable by calculus.[36]

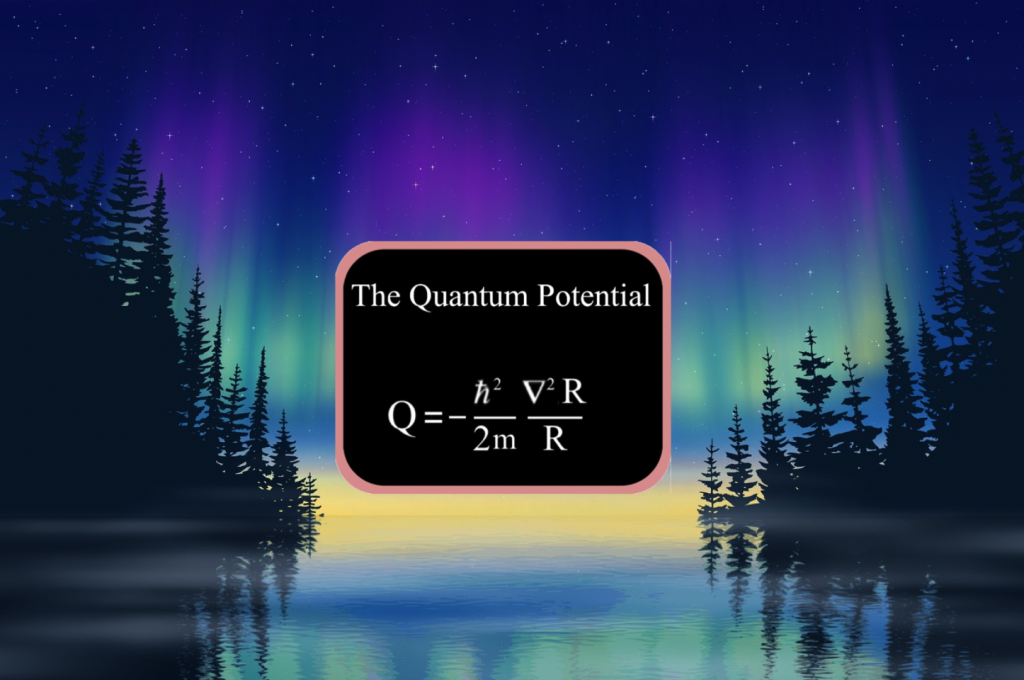

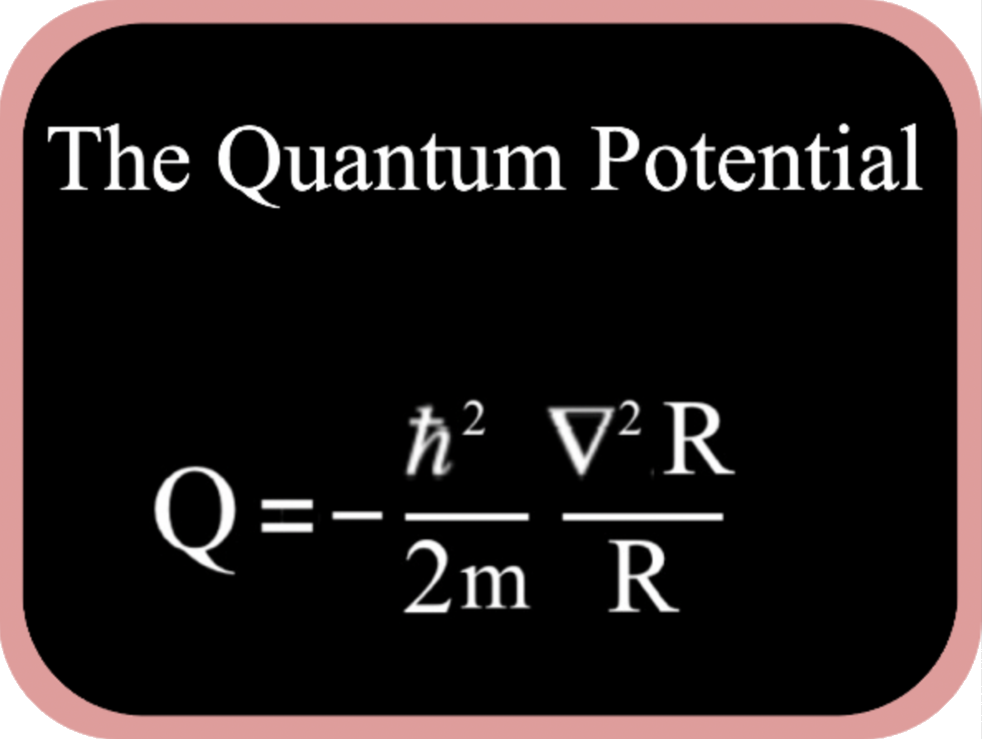

The way out of the conundrum lay buried in Schrödinger’s equation. By manipulating the equation, Bohm and B. J. Hiley found the proverbial thread that, when pulled, revealed a whole new realm of reality that Bohm christened the quantum potential, bearing the symbol Q.[37]

Quantum Potential

(See equation in left margin)

“Central to understanding the Bohm interpretation [of quantum events] is the appearance of the quantum potential, Q,” explains Hiley. “It is not ad hoc, as suggested by Heisenberg, but emerges directly from the Schrödinger equation and, without it, energy would not be conserved.” Let me underscore: without Q, energy would not be conserved. “The quantum potential,” continues Hiley,

does not have the usual properties expected from a classical potential. It does not arise from an external source; it does not fall off with distance. It seems to indicate a new quality of internal energy and, more importantly from our point of view, it gives rise to the notion of participation, non-separation, and non-locality.

At the deeper level it arises because, as Bohr often stressed, it is not possible to make a sharp separation between the observing instrument and the quantum process while the interaction is taking place. The Bohm approach makes a logical distinction between the two, but then the quantum potential links them together again so that they are actually not separate. It is this factor that gives rise to context dependence and to the irreducible feature of participation between relevant features of the environment in the evolution of the system itself.[38]

With this, Wigner’s objection is refuted; the human-experienced world is not exempt from quantum reality, after all. Participation and nonseparation render size, scale, and boundaries meaningless—human-made illusions, in other words.

Aboriginal societies have known this forever. Pick a Pintupi Aborigine from 1 to 15,000 years ago—any Pintupi—and he could tell you as much. So could Goethe, in his own way: “The manifestation of a phenomenon is not detached from the observer; it is caught up and entangled in his individuality.”c Plotinus appears to have realized this, as well, when he discusses a subject’s “judging faculty” receiving an “imprint” or “partak[ing] of the state” of an object.d Elsewhere he talks about “Contemplation and its object constitut[ing] a living thing, a Life, two inextricably one. The duality, thus, is a unity.”e

The third thing (besides participation and nonseparation) a Pintupi would explain, after his own fashion, is nonlocality, as did Plotinus.

It is no longer a question of earth alone, but of the whole star-system, all the heavens, the Cosmos entire. For it would follow that, in the sphere of things not exempt from modification, sense-perception would occur in every part having relation to any other part. f

“The appearance of non-separability and non-locality in the Bohm approach,” adds Hiley, “led Bell indirectly to his famous inequalities”—that is, to the inconvenient truth of nonlocality, the third element in the holy trinity of wildness.[39]

Quantum potential may have been a revelation to the supermen of physics. It certainly was not to Paul John and the other Yup’iks in the room that brisk autumn day in 1994. For them, it was Yuuyaraq, the Way of the Human Being.[40]

With Q, Adam’s Wall and the subject-object dichotomy collapse definitively, fatally. This may not have troubled Stephen Hawking or the fish and game biologists in Bethel, all of whom were in the business of prediction and practical outcomes, but it troubles me. Michelangelo’s Adam begat the superman of physics who, like Descartes resolving to doubt everything in his search for ultimate truth, strips himself of every fiction to find the real—strips himself, that is, of “every fiction except one,” corrects Stevens: “the fiction of an absolute.”[41] When Bohm blew the whistle on this final fiction to Oppenheimer et al., they excommunicated him as a heretic.

If Q is heresy, so be it; it is still the truth. Q has slain the false god of the absolute.

Append this manifesto to Nietzsche’s “God is dead!”[42] In The Gay Science, Nietzsche invents a madman, a 19th-century Jeremiah, crying out in a busy marketplace, “‘Where is God?’” Silence. “‘I’ll tell you!,’” he shouts at the astonished throng. “‘We have killed him—you and I! We are all his murderers. But how did we do this?’” We did it, says Nietzsche in his numerous books, through the Renaissance superman, the brave new world of the Enlightenment. “‘Do we not ourselves have to become gods merely to appear worthy of it [murdering God]?'” asks the mad prophet. “‘There was never a greater deed—and whoever is born after us will on account of this deed [slaying God] belong to a higher history than all history up to now!’”[43]

“‘All gods are dead,’” spoke Zarathustra; “‘now we want the Superman to live!’”[44] Prophetic words. The superman of science is the supreme Übermensch. Except that he, too, believes in the absolute—the fatal flaw, the Achilles heel of empiricism. “As soon as . . . a philosophy begins to believe in itself,” warns Nietzsche, “it always creates the world in its own image. It cannot do otherwise. Philosophy is this tyrannical impulse itself, the most spiritual Will to Power, the will to ‘creation of the world,’ the will to the causa prima.'”[45] Such a philosophy is science.

The absolute is dead! Thus spoke Bohm. If science slew the absoluteness of God, Q shattered the absoluteness of science. With its death, the absolutist enterprise that has wreaked havoc in its ten-thousand-year rampage—“the era of the idea of god / and the idea of man”—is unmasked as nothing more sacred, rational, logically profound, or privileged than Nietzsche’s will to power.[46] Granted, Professor Hawking, the will to power worked and still works in the laboratory, but unfortunately the data don’t happen to be true.

__________________

Footnotes

[1] Jean-Jacques Rousseau, “Lettre I de milord Edouard, Cinquième partie,” in Julie, ou la nouvelle Héloïse (1761); 1 Corinthians 13:11 (KJV).

[2] Arthur Schopenhauer, The World as Will and Representation, trans. E. F. J. Payne, vol. 1 (New York: Dover, 1969), 3, emphasis mine.

[3] See Calvin Luther Martin, In the Spirit of the Earth: Rethinking History and Time (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992), for an analysis of the switch from the hunting, gathering, and fishing of the Paleolithic, which derive from the principle of animal kinship and the gift, to systematic agriculture and animal domestication via the invention of sky gods, a “chosen people,” and historical consciousness in the Neolithic.

[4] For Chaos and Old Night, see Thoreau, Maine Woods, 94,

[5] Eiseley, “The Dance of the Frogs,” in The Star Thrower, 106; Oliver, “Pink Moon—The Pond,” in Twelve Moons, 7–8.

[6] Jung, Memories, 272, 273.

[7] Stevens, “Esthétique du Mal,” in Collected Poems, 341.

[8] The phrase, “logical lunatic,” is from Stevens, “Esthétique du Mal,” in Collected Poems, 341.

[9] Coetzee, Lives of Animals, 54.

[10] See René Descartes, Principles of Philosophy, trans. Valentine Rodger Miller and Reese P. Miller (Boston: Kluwer Academic, 1982), 21, 5–6, 39–41.

[11] Descartes, Discourse, 38.

[12] Job 42:10–12 (KJV).

[13] Hegel, Jenenser Realphilosophie, 211. See note 19, Lecture 6, for the original German. Gerald Bruns points out that Adam, by his speech (naming), “annihilated the immediate presence of the world and in its place established a mediating or ideal presence—the word.” Bruns, Modern Poetry, 191.

[14] Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Hegel’s Philosophy of Mind, trans. William Wallace (Oxford: Clarendon, 1894), 85 (§462), emphasis his.

[15] Marshall D. Sahlins, Culture and Practical Reason (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1976), x.

[16] See Jim Holt, “Something Faster Than Light? What Is It?” New York Review of Books, November 10, 2016.

[17] Wheeler, “Bohr, Einstein, and the Quantum,” 26–28.

[18] Sahlins, Stone Age Economics (Chicago: Aldine/Atherton, 1972), 186n.

[19] Wheeler, “Bohr, Einstein, and the Quantum,” 7, emphasis his.

[20] Bohm, Wholeness and the Implicate Order, 11, emphasis his.

[21] Bohm, Wholeness and the Implicate Order, 48–49.

[22] Bohm, Wholeness and the Implicate Order, 151.

[23] Erwin Schrödinger, from “Mind and Matter,” in What Is Life? With Mind and Matter and Autobiographical Sketches (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1967), 135–36.

[24] Wheeler, “Bohr, Einstein, and the Quantum,” 7–10.

[25] See the Gargantua and Pantagruel series of books by François Rabelais (ca. 1494–1553). Note, especially, Pantagruel.

[26] See Eric R. Wolf’s Europe and the People without History (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982).

[27] Albert, Quantum Mechanics and Experience, 80–111.

[28] Albert, Quantum Mechanics and Experience, 73–79, 81–83, 129, 170–76.

[29] This passage from David Bohm’s introduction to Wholeness and the Implicate Order is worth reading:

Physicists tend to [adopt] the attitude that our overall views concerning the nature of reality are of little or no importance. All that counts in physical theory is supposed to be the development of mathematical equations that permit us to predict and control the behaviour of large statistical aggregates of particles. Such a goal is not regarded as merely for its pragmatic and technical utility: rather, it has become a presupposition of most work in modern physics that prediction and control of this kind is all that human knowledge is about.

This sort of presupposition is indeed in accord with the general spirit of our age, but it is my main proposal in this book that we cannot thus simply dispense with an overall world view. If we try to do so, we will find that we are left with whatever (generally inadequate) world views may happen to be at hand. Indeed, one finds that physicists are not actually able just to engage in calculations aimed at prediction and control: they do find it necessary to use images based on some kind of general notions concerning the nature of reality, such as “the particles that are the building blocks of the universe”; but these images are now highly confused (e.g., these particles move discontinuously and are also waves). In short, we are here confronted with an example of how deep and strong is the need for some kind of notion of reality in our thinking, even if it be fragmentary and muddled. (xiii–xiv, emphasis his)

[30] Holt, “Something Faster Than Light.”

[31] Rilke, “Eighth Elegy,” 47–51, emphasis his.

[32] Leo Spitzer, quoted in Gerald Bruns, Modern Poetry, 39. Bruns goes on to comment, “A more radical solution to the problem of language [that is, ‘the confusion of words and things’]” in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Europe “called for the substitution of language by mathematics, on the grounds that, unlike the meaning of a word, the value of the mathematical sign can be measured with a precision that is very nearly absolute” (42).

[33] Rainer Maria Rilke, Letters to a Young Poet, trans. Mark Harman (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011), 29.

[34] Albert, Quantum Mechanics and Experience, 112–13. Interestingly, Everett was one of John Archibald Wheeler’s PhD students at Princeton. Wheeler, well known for his graciousness, thought Everett’s theory was worthy of consideration.

[35] David Bohm, Quantum Theory (Garden City, NY: Dover, 1951), 167, author’s note at bottom of page.

[36] B. J. Hiley, a theoretical physicist and brilliant mathematician, argued that the enigmatic wave functions of quantum events were best understood by resorting to non-commutative algebra. See Hiley, “Non-Commutative Geometry, the Bohm Interpretation, and the Mind-Matter Relationship,” manuscript sent to me by Hiley, 6–15. I gather this was a paper he read at a conference. A footnote on p. 1 reads: “To appear in Proc. CASYS’2000, Liege, Belgium, August 7–12, 2000.”

[37] See B. J. Hiley, “From the Heisenberg Picture to Bohm: A New Perspective on Active Information and Its Relation to Shannon Information,” in Proceedings, Quantum Theory: Reconsideration of Foundations, ed. A. Khrennikov (Sweden: Växjö University Press, 2002), 141–162. Offprint sent to me by B. J. Hiley, 5–6, 9–17.

[38] Hiley, “Non-Commutative Geometry,” 3, emphasis his. I have fixed typos and punctuation in Hiley’s text. For more on the significance of Q, see Hiley, “From the Heisenberg Picture to Bohm,” 5, 14–17.

[39] Hiley, “Non-Commutative Geometry,” 3.

[40] See Martin, Way of the Human Being.

[41] Stevens, “It Must Give Pleasure,” in Selected Poems, 125.

[42] Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, 41, 114.

[43] Nietzsche, The Gay Science, 119-120.

[44] Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, 104.

[45] Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil: Prelude to a Philosophy of the Future, trans. Helen Zimmern (New York: Macmillan, 1907), 14. Note that I have taken liberties with punctuation for clarity, without altering Nietzsche’s meaning.

[46] Stevens, “A Thought Revolved,” in Collected Poems, 196.

~