The Cave

Part 1

Calvin Luther Martin, PhD

November 3, 2024

The Bulky One

Prof. N. Scott Momaday

To understand the Grand Unified Theory one must begin by descending, as it were, the ladder at sisna-te-l along with all those Pleistocene caves I keep referring to, as the Keeper of the Game invited Turquoise Boy to do in the Navajo myth. Here we find Equus, and here we come home to our ancestral consciousness and language.

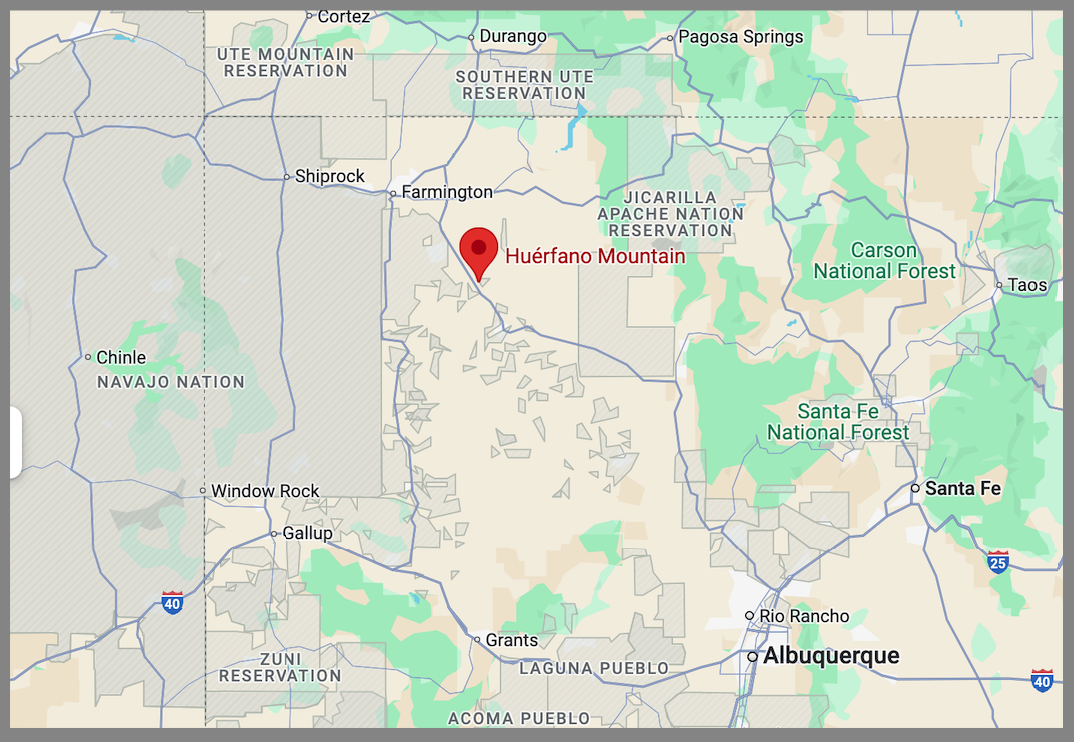

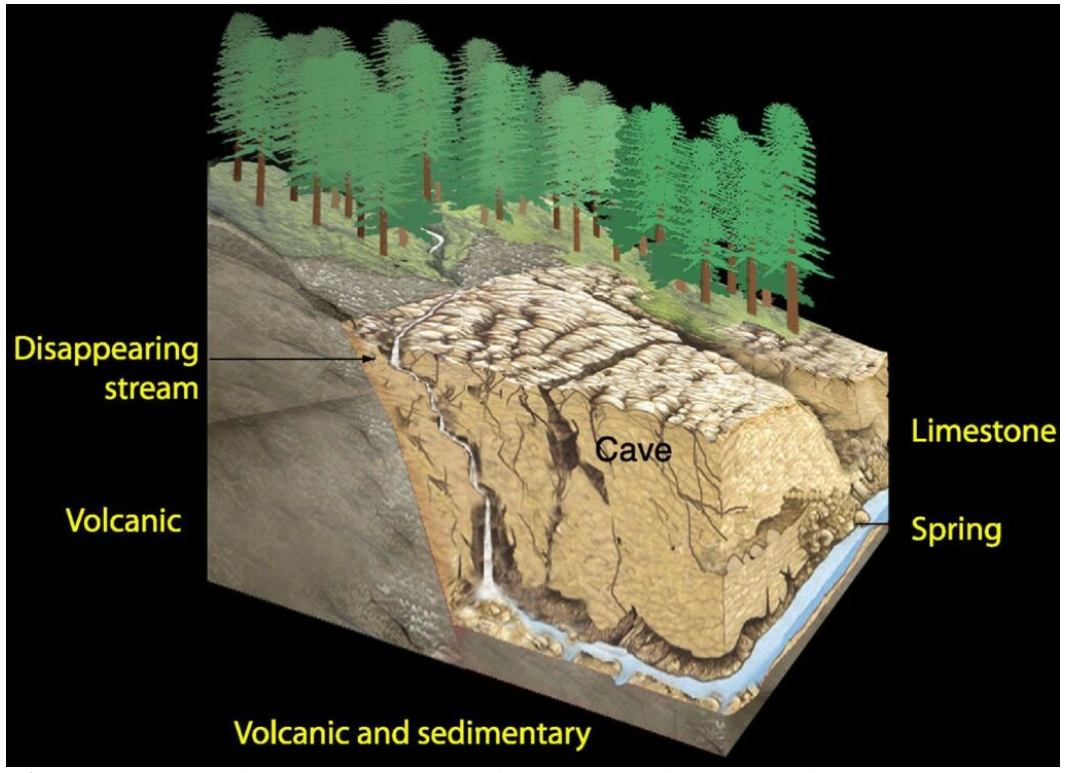

You will need to enlarge the above PDF to view it properly. Do this by clicking on the icon in the menu bar that resembles a TV with a triangle in the center. Once you have enlarged the PDF, find New Mexico on the map, then consult the Legend (Explanation) in the lower left corner which explains the significance of the colors. I have included this map to illustrate the extensive karst features in the State of New Mexico.

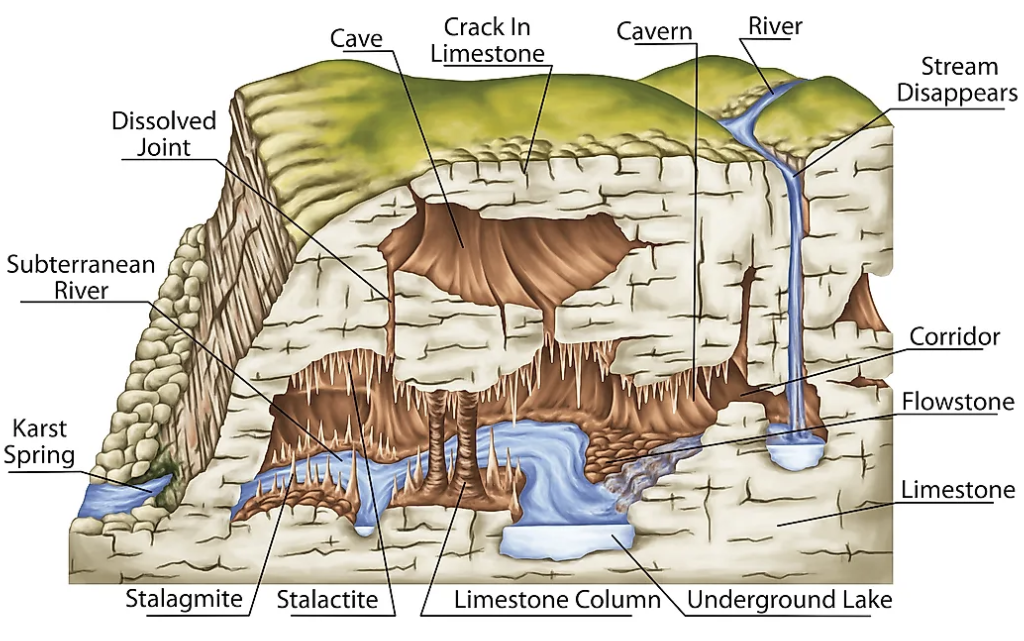

Passageways, channels, corridors, galleries, vast chambers — carved, molded and mortared by water

A cave is a massive ocarina. A vast musical instrument. A gigantic wind instrument.

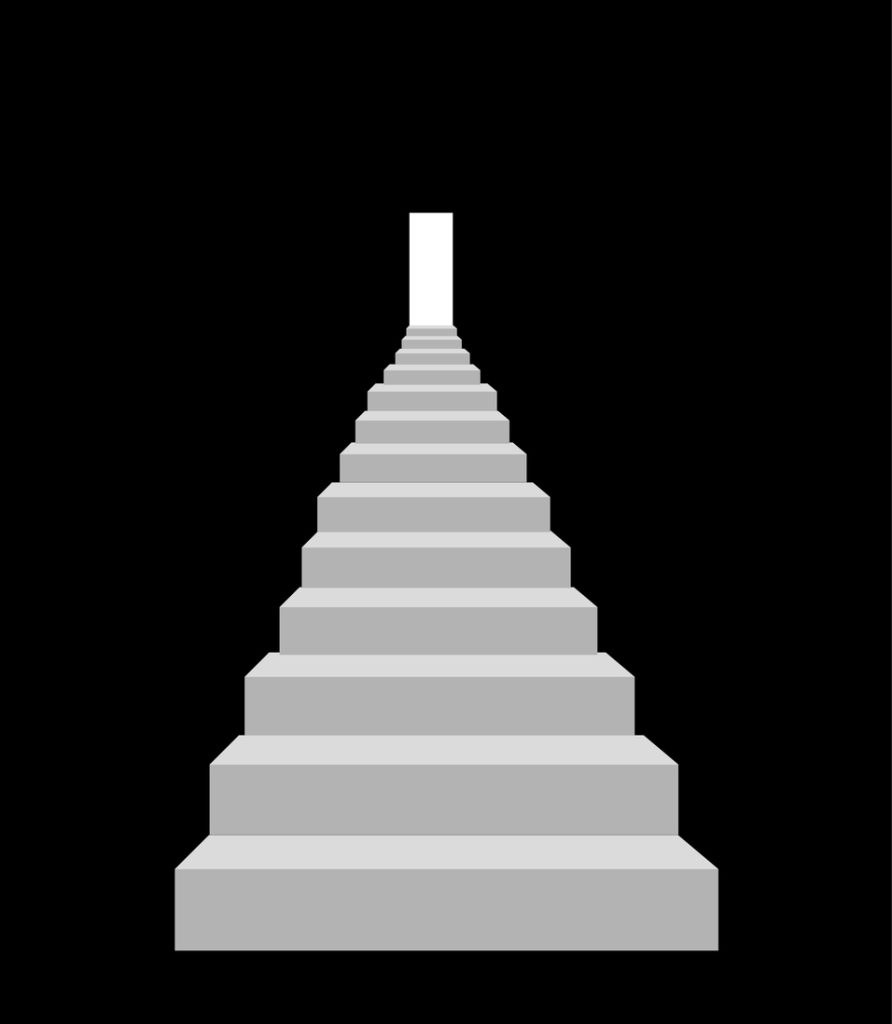

Dził Náʼoodiłii (‟Encircling Mountain”) is a sandstone mesa at the center of the aboriginal Dinétah, roughly equidistant from the four sacred boundary markers to the east, south, west, and north—mountains, all of them. Dził Náʼoodiłii is different from the others; it is not a boundary marker. Navajos see it as a numinous mythic passageway originating deep underground and reaching skyward. A kind of chthonic-cosmic ladder suspended ‟from the sky with sunbeams.”[1] Here First Man and First Woman emerged from a series of lower rungs. Here Changing Woman, mother of Turquoise Boy, was born. Some call Dził Náʼoodiłii the lungs of Dinétah: the place where man and woman first drew the sacred breath, the Holy Wind, of life.[2]

It was to this most sacred place that Changing Woman sent her son in the final stage of his quest. “There is just one thing left, my son. You shall now go to the place called sisna-te-l” — a cave, it turns out, in the vicinity Dził Náʼoodiłii. a Here he must descend the ladder of human consciousness and meet the Keeper of the Wild Things.[3]

From the east, Equus has been created in hózhó: this he had already accomplished. And so on, through all the remaining cardinal points, including the sky:

From the south, Equus has been created in hózhó.

From the west, Equus has been created in hózhó.

From the north, Equus has been created in hózhó.

From the zenith of the sky, Equus has been created in hózhó.

Now, my son, you shall go to the place of origins called sisna-te-l, the nadir of the earth, and be shown Equus in hózhó.

When he got there, he found an entrance to a cave, just as his mother knew he would. Peering within, he saw ‟a certain person . . . sitting . . . below, they say. An old man, a very fat one (literally, ‟very bulky”) was sitting there, they say. A woman, likewise very fat, was sitting there, they say, also. A young man also was sitting there, they say. A young woman, equally so (very bulky) was sitting there, they say, also.” The creatures were a family — husband, wife, and their two children — remarked Cháálatsoh to Sapir.[4]

Cháálatsoh´s graphic description of these individuals is significant. Two things we must keep in mind. First, like all spirit beings, including animals, they exist in superposition. Thus, they can appear as both human and animal. Second, remember what I have said repeatedly in previous lectures: ‟language is physics.” Words make things happen. Cháálatsoh knew this. As the story unfolds, the old man´s words will make things happen.

Focus on these ‟very bulky” beings. As you read on, you will come face to face with their Pleistocene ancestors inhabiting the labyrinthine karst galleries of Chauvet, Hohle Fels, Geissenklösterle, and dozens of other nodes where Ice Age man and woman, exactly like Turquoise Boy, made contact with the same ‟keepers of the game” — the keepers of the potent wild things (including Equus) rippling and emerging from limestone walls.[5]

But I get ahead of myself. The old man´s daughter was the first to notice the visitor.

‟My father, someone is standing up there,” she said, they say. ‟An earth man is standing up there,” she said, they say. ‟Who can be walking about, as you say,” he (her father) said, they say? ‟But he is standing up there,” (she said). This happened four times, they say.[6]

Don´t be put off by the repetitive litany. She is letting her father know that the human at the mouth of the cave has visited the sacred mountains to the east, south, west, and north — the sacred outer boundaries of hózhó. Likewise, don´t be put off by the repetitive phrase, ‟they say.” This is standard in Native American mythology. The phrase is a way of certifying that the story is ancient and authentic — authoritative because it has been repeated from time immemorial by the ancestors, who are by definition sacred. Rather like people in the Western cultural tradition invoking a biblical story, chapter and verse, to establish veracity.

With this knowledge, the old man, also known as Mirage Man, calls out, ‟Come in, my grandchild!” Descend the ladder “having twelve rungs, extend[ing] into the ground, they say.”[7]

As the young man descends and adjusts himself to the darkness, the old man asks the same question posed by the other gods, ‟What are you traveling about for, my grandchild? It must be your travels nearby we have been hearing of.” I am traveling ‟that our means of travel be created, my great uncle.” “My grandchild, it really exists here. . . . Here they are, those with which in time to come [blank] will live.”[8]

Success! We must appreciate what just happened. Something of monumental importance in the history of mankind has just transpired. An earth person has been invited by someone bulky into the labyrinthine, acoustically rich, moist place where, for well over 40,000 years, wild things the world over have dramatically and indelibly imprinted themselves on human consciousness.

You heard me right. I am saying that Cháálatsoh reprised, for Edward Sapir, the Navajo version of what happened at Chauvet, Hohle Fels, Geissenklösterle and numerous other late Pleistocene caves: the cognitive mechanism whereby herds of wild things entered the mind of man and woman: in vast underground galleries of karst caves.

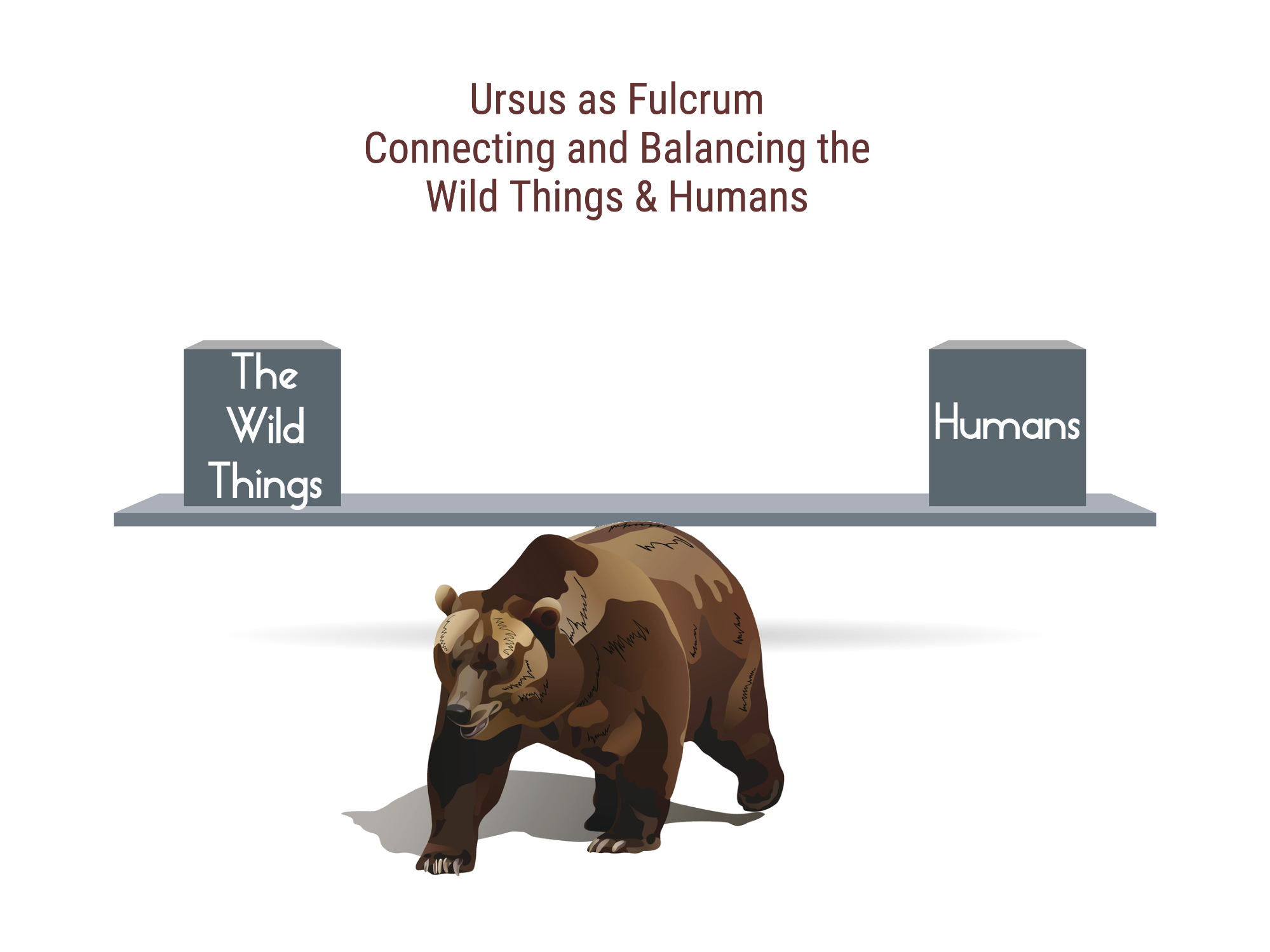

A heretofore anomaly in the mechanism is the fact that all these caves were frequented by Ursus, the Dark One. As Cháálatsoh acknowledges, and I shall explain further on, Ursus is the linchpin in the entire event. ‟Come in, my grandchild,” speaks Ursus, ‟what you are seeking really exists here. Now you will see it.”

For tens of millennia the Dark One has conveyed good news, a kind of gospel, to Paleolithic people, beginning with our Pleistocene forebears who left a visual record of it in caves — caves like sisna-te-l. (How the Dark One conveyed the message is something I shall explore further on.)

Many years ago I published a prize-winning book demonstrating, from North American historical and ethnographic sources, that the Dark One — yes, the one Eskimos refuse to talk about; yes, the one with ‟ears on the tundra” — has been the quintessential ‟keeper of the game” since time out of memory.[9] I see no reason why this role should not go back to the Pleistocene. (In this, I part ways with archaeologists.) As I hope to plausibly demonstrate, the Dark One has long been a bridge, a mediator, mentor, and guide for the hunter and the hunted — far longer than anthropologists and archaeologists are willing to concede.

Consider two 20th-century authors who incorporated this ‟keeper of the game” phenomenon in their works. In each case, Ursus is the centerpiece of a lengthy discourse on human-animal relationships. Faulkner´s ‟The Bear” is of course one of the works I have in mind. The hunters in the story call the bear, Old Ben, which suggests a feeling of affection mixed with awe and fear.

Ash and Boon say he comes up here to run the other little bears away. Tell them to get to hell out of here and stay out until the hunters are gone. Maybe. . . . He come to see who’s here, who’s new in camp this year, whether he can shoot or not, can stay or not. Whether we got the dog yet that can bay and hold him until a man gets there with a gun. Because he’s the head bear. He’s the man (emphasis added).[10]

Thus, Ursus as ‟game boss.”

Faulkner was famous for his devotion to hunting — always with the same cronies. It is said he declined to attend his Nobel Prize award ceremony in Stockholm, Sweden, because it interfered with his annual Mississippi hunting trip. Only pleading from the White House made him change his mind, so the story goes.

I can think of no writer more familiar with the culture of bear hunting than Bill Faulkner. When he writes the following lines, they are worth more than the usual attention one gives to a writer of fiction: “So I will have to see him,” resolves the boy, Isaac McCaslin, “without dread or even hope. I will have to look at him.” As I wrote in an earlier lecture, quoting one of the incredulous adults in the story, What was this boy “born knowing, and fearing too maybe, but without being afraid, that [he] could go ten miles on a compass because he wanted to look at a bear none of us had ever got near enough to put a bullet in and looked at the bear and came the ten miles back on the compass in the dark”?[11]

‟The Bear” is a chronicle of sorrow. An epitaph to the death of wildness. For Faulkner, nothing matches Ursus as embodiment and index of the ‟unhandseled globe” (Thoreau).[12] Ursus is the custodian and savior of wild things. As wildness dies, so does Ursus.

In the end, a timber company destroys Faulkner´s wilderness, physically and spiritually. The wave function collapses. Sam Fathers, the elderly Chickasaw who as tutored young Isaac McCaslin in the ancient protocols and etiquette of the hunt, foresees the collapse and sees to it that he dies before the clearcutting begins. Old Ben has the same premonition, which is why he resolves to let himself be killed. There is nothing Ursus can do to save this sacred landscape.

N. Scott Momaday takes Faulkner´s perception a step further. ‟Bear is a template of the wilderness.…Bear is the animal representation of the wilderness.… Bear is the keeper and manifestation of wilderness. As it recedes, he recedes. As its edges are trampled and burned, so is the sacred matter of his heart diminished.”[13]

Momaday, the first Native American to win a Pulitzer Prize, knew that somehow he, himself, was Ursus. ‟Bear and I are one, in one and the same story.”

One October I made a quest after Bear, in myself and in the wide night of the wilderness. For four days I camped on the east side of Tsoai (Devil´s Tower, Wyoming) and fasted. On the fourth night I felt strangely refreshed and expectant. The pangs of hunger that I had suffered through the day were gone. I felt a restoration of my body and spirit in the cold air. There was a perfect stillness around me.

The great monolith, Tsoai, rose above me in phosphorescent haze, drawn like a tide by the moon. It bore a kind of aura for a time, and then, as the night darkened to black, its definition grew sharp. Ursa Major emerged on the south side of its summit, as if the two things were in the same range of time and space. Then the constellation rode over Tsoai, descending across its northern edge. It must have taken a long time, but it seemed a moment. And besides, I too was looking beyond time, into the timeless universe.

Shadows deepened on the monolith, and in one of them appeared Bear, rearing in some fluent alignment with Tsoai itself, huge, indistinct, and imperturbable.

I was fulfilled in some sense, neither frightened nor surprised. It was, after all, the vision of my quest, and it was mine, and it was appropriate. I came away more nearly complete in my life than I had ever been.[14]

Faulkner and Momaday, two of America´s deepest thinkers, speak to the enduring presence of Ursus in human consciousness. ‟Bear is welcome in my dreams,” writes Momaday without any hesitation for how absurd this may sound to modern ears. With a nod to his Kiowa ancestry, he closes, ‟in that cave of sleep I am at home to Bear.”[15]

Before we enter the caves of Momaday´s dreams, I wish to note that the Navajo phenomenon of hózhó enfolding and unfolding itself as Equus appears to be the same order of reality perceived by Plato in the Idea and by the Neoplatonic Intellectual-Principle projecting itself in Beauty and Good. I like to think that David Bohm would have considered all three to be doorways to the cosmic reality he called the implicate order.

Taking this a step further, I see a kind of Grand Unified Theory of human consciousness and language in the intersection of (1) Platonism (as we shall soon see with Socrates in ‟The Cratylus”); (2) Sanskrit linguistics (see the works of Bhartrhari); (3) Neoplatonism´s Intellectual-Principle; (4) Paleolithic cosmology, including its presentation in the chthonic cathedrals of Chauvet et al. and Cháálatsoh´s narrative; and (5) Bohm´s quantum potential within the untouchable, impenetrable, impalpable implicate order.

This Grand Unified Theory begins with caves, and so shall I. Later, I will add Ursus to the caves. And still later, I will add ‟woman” to the caves. ‟Man,” himself, will be notably absent. Yes, of course, he is present in the Late Pleistocene community of life, but he definitely does not dominate the story. Nor will he for tens of thousands of years, not until he explodes upon the oral and clay tablet narrative as ’ādām, the farmer, most notably and fatefully in the ancient Semitic story we know as the Genesis story composed by the children of ’ādām. The story outrageously featuring a male sky god summoning creatures ex nihilo from land and sea for domination by the pastoralist (see the Book of Job) and tiller of the soil. The story invoked by Francis Bacon as the divine charter for a new, pragmatic, data-driven, take-no-prisoners technological and scientific dominion over the earth and its wild and savage host. (You would do well to read Bacon´s New Atlantis, especially if you want to understand the agenda of the modern university in this ‟Novum Organum.”)

In the Pleistocene Pangaea of wildness, where there are no sky gods, no ’ādām, no so-called animal domestication (enslavement) or systematic agriculture (and agrarian/biblical arrow of time), no subject-object rift, no res cogitans or res extensa, nor whiff of good versus evil — here wild things emerge from karst caves under the influence of Ursus and ‟woman.” Here, before the Great Forgetting erases it, the human-animal relationship conforms to the protocols of the ‟gift.” Here, everything is opposite to the Alice in Wonderland, topsy-turvy Baconian, Newtonian, Cartesian ‟will to power” masquerading as a quest for knowledge.

We return to humanity´s quest for the things that have no name, as they manifested themselves in damp subterranean places curated by creatures which likewise have no name and who, I remind you, Eskimos won´t talk about. The one interrogated by Turquoise Boy was called, simply, ‟Grandfather” (‟Great Uncle”) — an honorific title that has continued in use in North America well into our own time.[16]

Damp subterranean places. Equus emerged from this matrix, say the Navajo mythtellers. ‟The predominance of isolated high-lying areas bordered by lofty cliffs,” such as Canyon de Chelly, ‟favors the emergence of subsurface water,” wrote Herbert Gregory in his 1917 USGS report on the ‟Geology of the Navajo Country.” ‟Surfaces otherwise dry are kept moist, and weathering is greatly facilitated. . . . The Navajo country is a region of springs and seeps,” spectacular sandstone cliffs, ‟caves and alcoves and pits sunk deep into canyon walls,” testimony to ‟erosional work by groundwater.”[17]

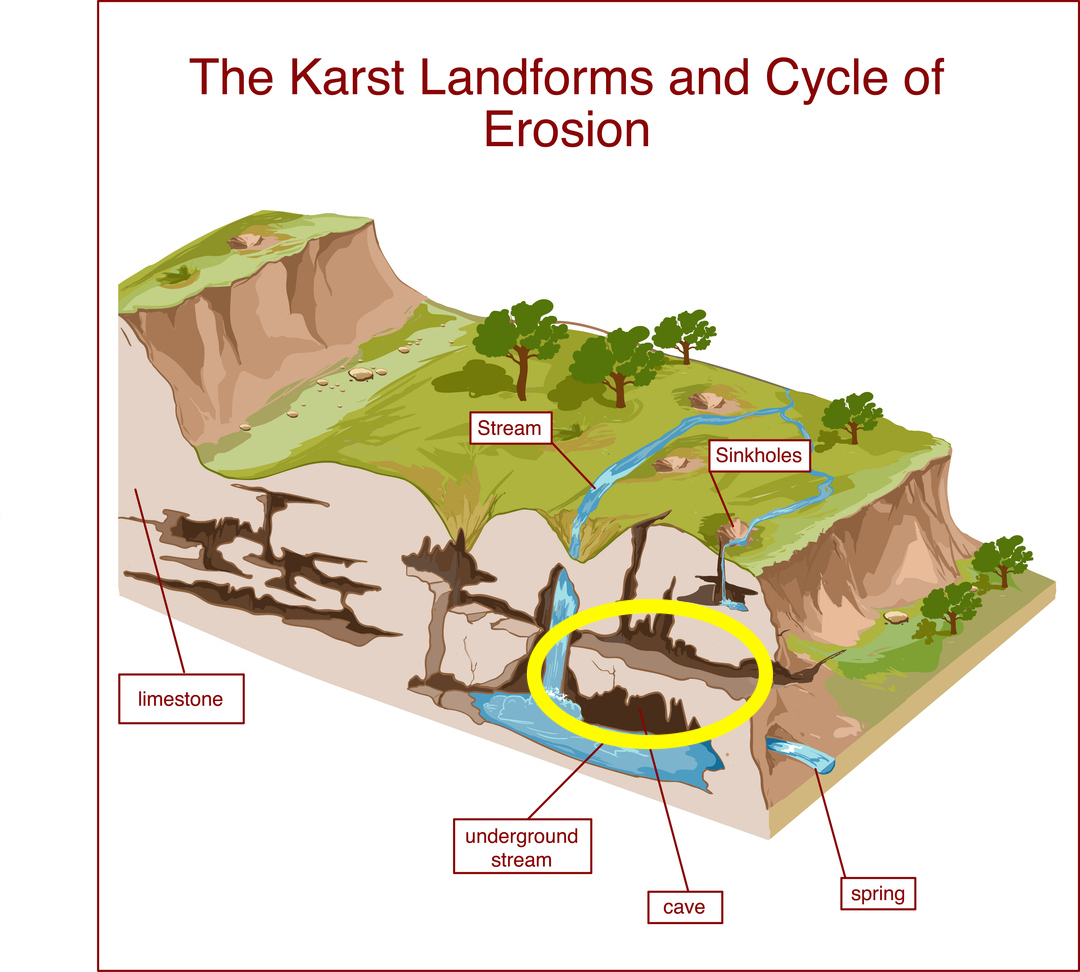

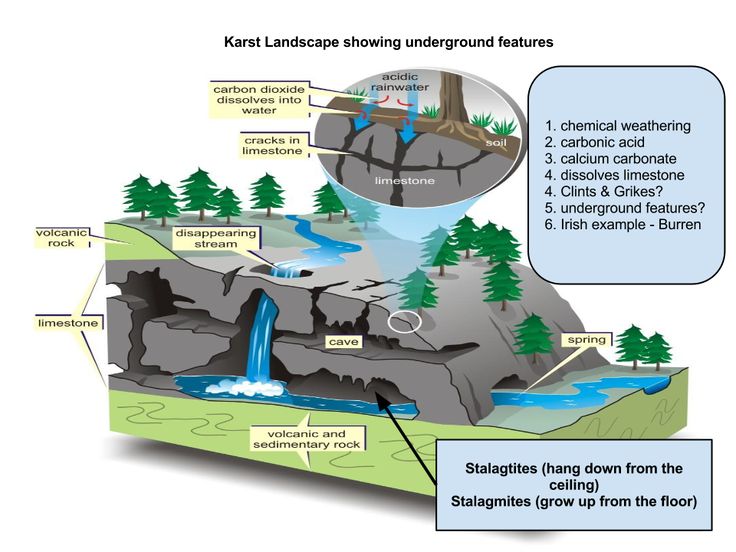

Besides sandstone features like sisna-te-l at Dził Náʼoodiłii (‟Encircling Mountain”), there are karst formations — remnants of vast coral beds laid down by primordial seas — in the northern and eastern reaches of Dinétah. Beds of calcium carbonate (limestone) and calcium sulfate (gypsum) that became woven into the continents as they floated, like dinner plates, across the earth´s mantle.

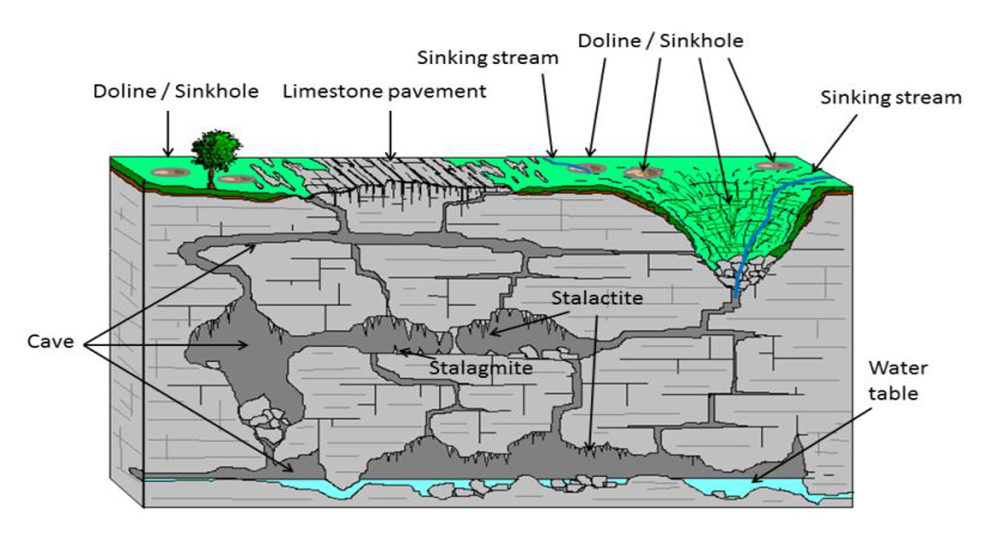

Within these karst formations, caves originated over millions of years from the gradual yet relentless dissolution of surface limestone, ‟when laminar flow is the only method that can carry water through the minuscule fissures and holes in the rock mass. . . . Turbulent flow is [eventually] established and the flow rate increases when the width of the apertures approaches a critical threshold, which is slightly less than one centimeter.”[18] From such humble beginnings, less than a centimeter wide, begin the rifts that yield the wombs we know as Chauvet or Hohle Fels or what have you.

Turbulent flow ‟makes this flowpath larger than the adjacent ones, because it enables the water in these enlarged holes to maintain its chemical aggression over longer paths. This results in th[is] path being chosen as the primary one in the near term, directing the majority of the water flow through it and increasing its width even further. This leads quickly to the beginning phase of the creation of a real cave tunnel.[19]

Here is another description of the process.

Infiltrating rainwater or meltwater containing CO2 from the atmosphere or soil enters the subsurface, circulates in the fissures and fractures of the [limestone or gypsum] carbonate rock, and results in karstification [formation of a cave, sinkhole or other underground drainage complex].

Karstification is a self-amplifying and selective process; higher through-flow and chemical dissolution occurs along the largest open fractures, leading to accelerated growth of their apertures and eventually to the formation of hierarchically connected networks of widened fractures, conduits and caves, which typically converge into a single master conduit drained by one large spring.[20]

The sculpted rock walls within the conduits and smaller channels attest to the tremendous force of the water that once flowed through them, like the blood flows that literally carve the chambers in the embryonic human heart.

The shape of scallops, which are erosional cusps left by turbulent running fluids, can be used to infer flow direction. The size of these scallops makes it possible to determine the flow velocity during the time of their formation — the larger they are, the slower the water was moving.…

Sediments that built up on the floors of underground rivers can protect the lower part of the channel from erosion and corrosion. As a result, the water will be able to carve out alluvial notches, or lateral grooves on the walls that are somewhat undulating and subhorizontal.…

Eventually, sediments may wash out of these passageways, creating a passageway that resembles a canyon.[21]

The dynamism is striking: the creation of an organ resembling a chambered heart in the body of the earth. Instead of a Middle Eastern garden of frugivorous delight, there are passageways, channels, corridors, galleries, niches, alcoves, even vast chambers — carved, molded and mortared by water. Water is omnipresent; it moves and speaks as condensation, drips, seeps, trickles, rivulets, a stream or lake. Perhaps in a river deep beneath echoing chambers and corridors. Meanwhile all is enveloped in cool, damp, thick darkness.

If there truly are chthonic powers that mankind can grasp and be grasped by, surely they are in such a place.

Water was fundamental. ‟If there is magic on this planet, it is contained in water,” reflects the evolutionary biologist Loren Eiseley, recalling how he once lay on his back in a remote stretch of the Platte River and allowed it to carry him whithersoever it would. ‟I had the sensation of sliding down the vast tilted face of the continent” and realizing that humans are in truth nothing more than ‟animalized water” that has ‟changed its shapes eon by eon to the beating of the earth´s dark millennial heart.”[22]

Surely there is no better place to experience the beating of this heart than here:

He found himself in a lofty cavern … of vague outline.… The air in the cave was glacial, penetrated to the very bones.[23]

The description is not Eiseley´s, although it sounds like him. It´s from Willa Cather. The locale is the Pajarito Plateau, New Mexico, renowned for its ancient cave communities now preserved as Bandelier National Monument. Cather was familiar with the area. She found it magical. I have lived near this plateau, in Santa Fe, and can affirm there is something uncanny about it.

Cather wrote the scene into, Death Comes for the Archbishop, her novel about the real-life French missionary, Father Jean-Marie Latour. A magnificent story. Surely one of the best in American literature.

The cave is volcanic, not karstic. Yet in other respects Cather’s description fits well the limestone caves of Chauvet, Hohle Fels, and Geissenklösterle, which seem to be the oldest so far discovered of a host of late Pleistocene limestone caves wherein anatomically fully modern humans left voluminous evidence of the world they perceived and experienced.

“Padre,” said the Indian boy, “I do not know if it was right to bring you here. This place is used by my people for ceremonies and is known only to us. When you go out from here, you must forget.”[24]

Cather is absolutely right; these places always have been tremendously sacred.

Notice, below, a dimension generally absent from descriptions of caves: the sound.

The dizzy noise in Father Latour’s head persisted. At first he thought it was a vertigo, a roaring in his ears brought on by cold.… But as he grew warm and relaxed, he perceived an extraordinary vibration in this cavern; it hummed like a hive of bees, like a heavy roll of distant drums.[25]

The vibration that ‟hummed like a hive of bees” throughout the cavern and gave him vertigo (dizziness) was the ‟voice” of the cave, a phenomenon well known to archaeo-acousticians.[26]

‟Vast caves are not straight tubes,” explains the legendary cave physicist, Giovanni Badino (1953-2017), ‟but show intricate morphologies and are in general connected to the external side of the mountains through different entrances placed at different heights.” With the result that caves like Latour´s have their own meteorology, their own distinct weather — a dynamic interplay between cave winds, barometric pressure, moisture, and external atmospherics. ‟Wind signals … contain information on the cave´s response to external pressure fluctuations, information that can be extracted using standard signal processing techniques under the form of infrasonic resonances. It is therefore tempting to approximate . . . cave[s] to a Helmholtz resonator.”[27] Badino calls caves ‟the biggest natural wind instruments on earth.”[28]

___________

Footnotes

[1] Harold Carey, Jr., ‟Huerfano Mesa: Navajo Sacred Mountain,” in Navajo People: Information about the Dine (Navajo People), Language, History, and Culture (January 15, 2013): https://navajopeople.org/blog/huerfano-mesa-navajo-sacred-mountain/

[2] See Frank Waters, Masked Gods: Navaho and Pueblo Ceremonialism (Denver: Sage Books, 1950), pp. 167-168.

[3] Sapir, Navajo Texts, p. 119.

[4] Sapir, Navajo Texts, p. 119.

[5] See Calvin Martin, Keepers of the Game: Indian-Animal Relationships and the Fur Trade (1978).

[6] Sapir, Navajo Texts, p. 119.

[7] Sapir, Navajo Texts, p. 119.

[8] Sapir, Navaho Texts, 119.

[9] Martin, Keepers of the Game (1978).

[10] Faulkner, The Bear, p. 192.

[11] Faulkner, The Bear, 198, 241, emphasis his.

[12] Henry David Thoreau, The Maine Woods (1864), p. 94.

[13] Momaday, In the Bear´s House, pp. 9-10.

[14] Momaday, In the Bear´s House, p. 10.

[15] Momaday, In the Bear´s House, p. 11.

[16] Sapir, Navajo Texts, p. 119 – 123.

[17] Herbert E. Gregory, Geology of the Navajo Country, p. 119.

[18] Zarga, ‟Karst Topography,” p. 260.

[19] Zerga, ‟Karst topography,” p. 260.

[20] Goldscheider et al., ‟Global Distribution of Carbonate Rocks and Karst Water Resources,” p. 1662.

[21] Zerga, “Karst topography,” p. 261.

[22] Eiseley, Immense Journey, pp. 15, 19, 21.

[23] Cather, Death Comes for the Archbishop, p. 88.

[24] Cather, Death, p. 89.

[25] Cather, Death, p. 90.

[26] Badino, ‟Underground Meteorology,” p. 445.

[27] Badino, ‟Fluctuations of Atmospheric Pressure,” p. 5.

[28] Badino, ‟Fluctuations of Atmospheric Pressure,” p. 6.

- It’s impossible to pinpoint the location of sisna-te-l. Navajo mythology seems to place it in the vicinity of Huerfano Mesa. If the cave was karstic, it may not have been as close to the mesa as one would think, since there is no significant karst geology in the vicinity of the mesa. There are, of course, massive karst caves in southwestern New Mexico along with significant hypogene karst features in the Pecos River Valley of north-central Mexico. See Stafford et al., “The Pecos River Hypogene Speleogenetic Province,” Advances in Hypogene Karst Studies, NCKRI Symposium 1, (2009), p. 4; Doctor et al., “Progress toward a Preliminary Karst Depression Density Map for the Coterminous United States,” 16th Sinkhole Conference, NCKRI Symposium 8 (May 2020), p. 324, fig. 6.[↩]