Pisuk•a•ciaq

The Little Walker

Calvin Luther Martin, PhD

November 1, 2024

G. K. Chesterton

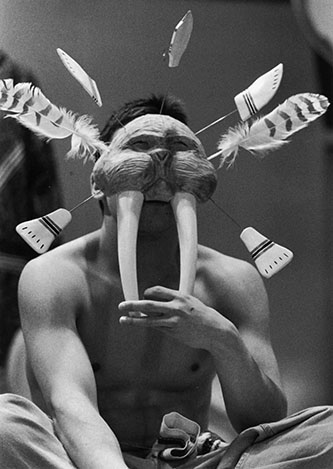

No subject-object split (James Barker photo)

In the Pangaea of Symmetry human and animal seamlessly, fluently mirror one another. “We have a sensation in our feet, as we feel the rustling of the feet of the springbok . . . making the bushes rustle. . . . We have a sensation in our face, on account of the blackness of the stripe on the face of the springbok. We feel a sensation in our eyes, on account of the black marks on the eyes of the springbok" (Kalahari Bushmen).

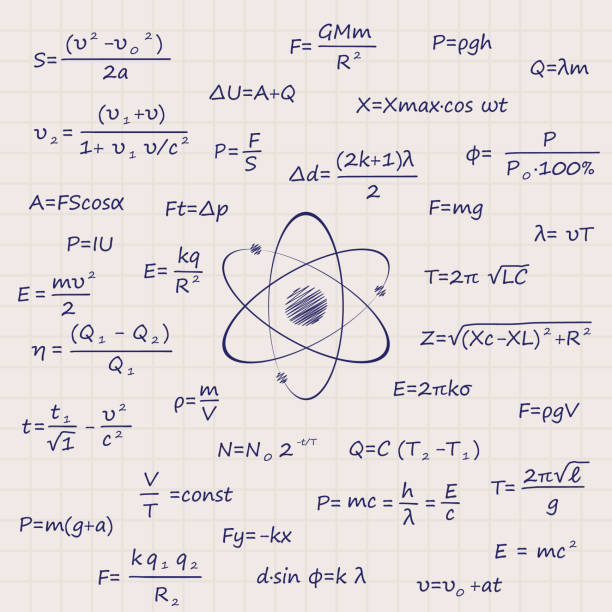

We control the earth and all that dwell therein through the language of mathematics which informs the science of physics and technology

Prof. Franz Boas

The Paleolithic Logos: “Bears got ears on the tundra” (Charlie Kilangak (The Puffin) says quietly.

The Paleolithic Logos: “I am a puffin and my son is, too” (Charlie Kilangak: The Puffin).

Kalahari Bushman woman

Steenbok

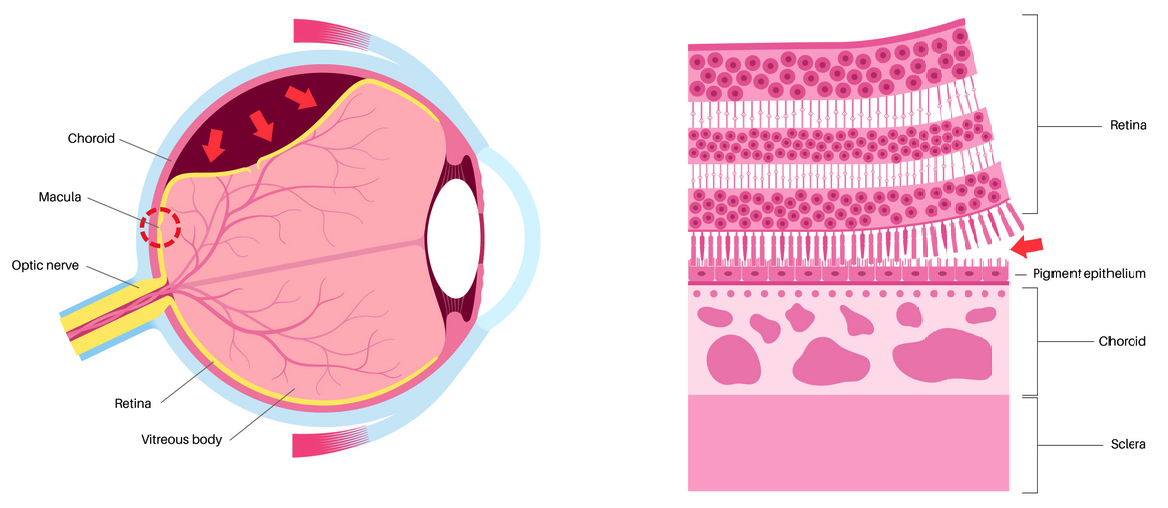

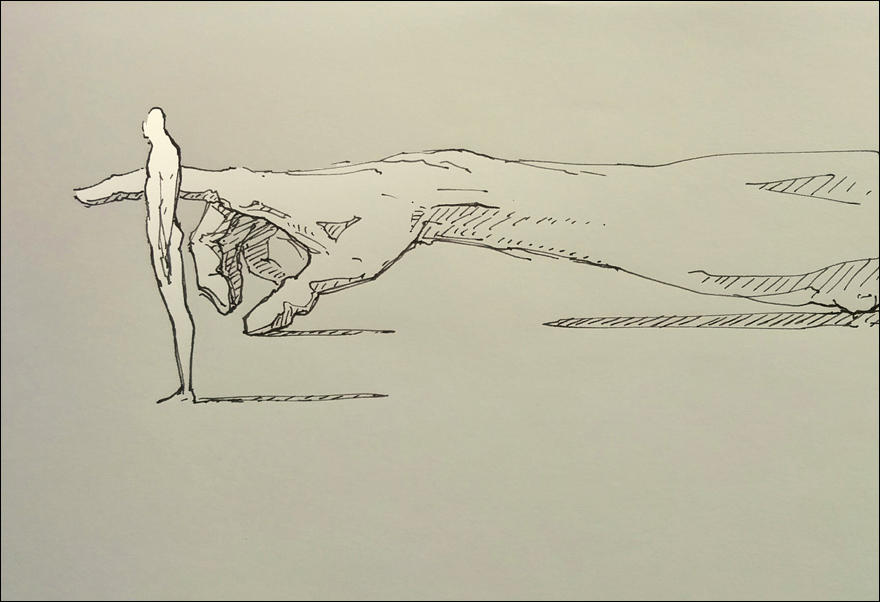

A smear of probability—a force field of various components momentarily converging within this presence best called, after all, a “little walker.” Vague, full of potential. Energy, after all.

G. W. F. Hegel

My wife, Nina Pierpont, MD, PhD, lived with these utterly magnificent creatures in the Amazon jungle for, all told, two years. Living in a tent. My wife walked trails, alone, with no gun — trails where these wild things also traveled. My wife was never harmed nor did she ever feel threatened of frightened — just exhilarated.

Carefully taking soundings while peering through the fogbank that, since Adam, has hidden this supercontinent from Western consciousness. “We seek,” Stevens probes further, "The poem of pure reality, untouched / By trope or deviation, straight to the word, / Straight to the transfixing object, to the object / At the exactest point at which it is itself, / Transfixing by being purely what it is.”

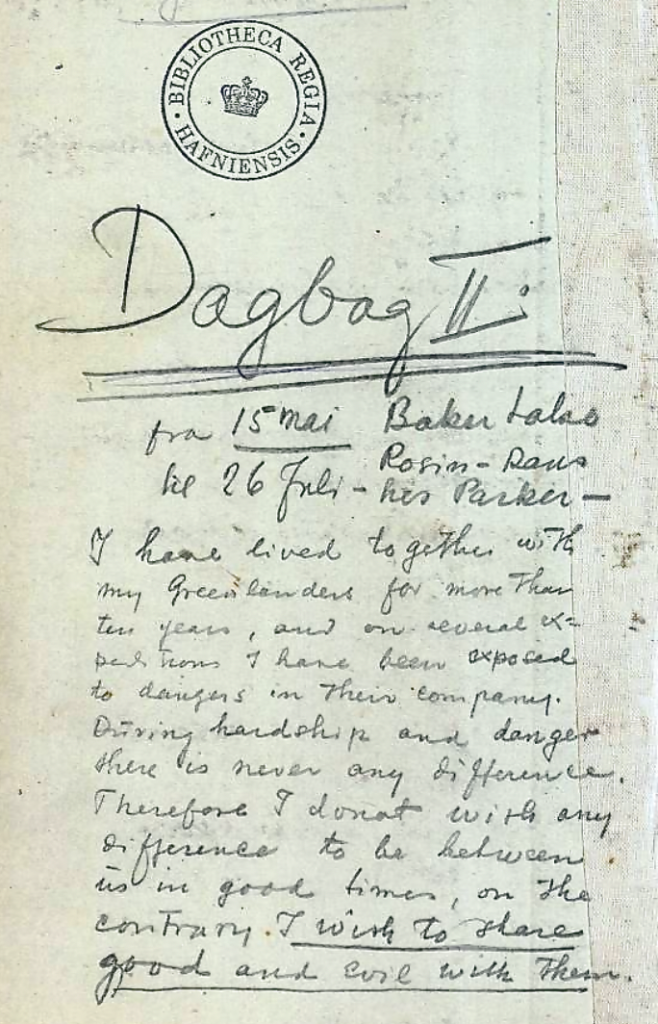

First page from Rasmussen’s journal of the 5th Thule Expedition, 1922

This is a fox. It is not a pisuk·a·ciaq (little walker). What creates the difference is the name, “fox.” It immediately makes a boundary. A Cartesian subject-object wall.

Consider Heidegger. “Language alone brings beings as beings into the open for the first time. . . . Language, by naming beings for the first time, first brings beings to word and to appearance. Only this naming nominates beings to their Being from out of their Being. Such saying is a projecting of clearing, in which announcement is made of what it is that beings come into the open as. Projecting is the release of a throw [as in throwing a ball] by which unconcealment infuses itself into beings as such. This projective announcement forthwith becomes a renunciation of all the dim confusion in which a being veils and withdraws itself."

Prof. Martin Heidegger

See the above PDF for Einstein’s explanation of the “field” principle in physics.

Werner Heisenberg, Nobel laureate 1932 for creating the field of quantum mechanics

“Let the wild rumpus start!” (“Where the Wild Things Are”)

Prof. John Archibald Wheeler

Read the highlighted passages in the article, above, by Wheeler (1989).

On the axis of wildness, Kacyon was corrected by a quantum-field-of-potential expressed as a kangilngaq.

Two cross-currents of fact. Both real. Both there. Neither one fiction or fantasy. Each accessed through language/consciousness.

“They ain’t nothin’ until I calls ’em.”

Click on the image, above, to listen to the luk-loó-nuk (brant), with thanks to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

Where everything is everything else. One long muscle.

N/om is inaccessible to language, measurement, and specificity. One might think of it as flowing movement suffusing everything. Like swift-flowing water sculpting each object and event (appearing as an eddy, riffle, vortex, standing wave, chute) in the immense inscrutable Presence the San call the “place where we live and who we are.”

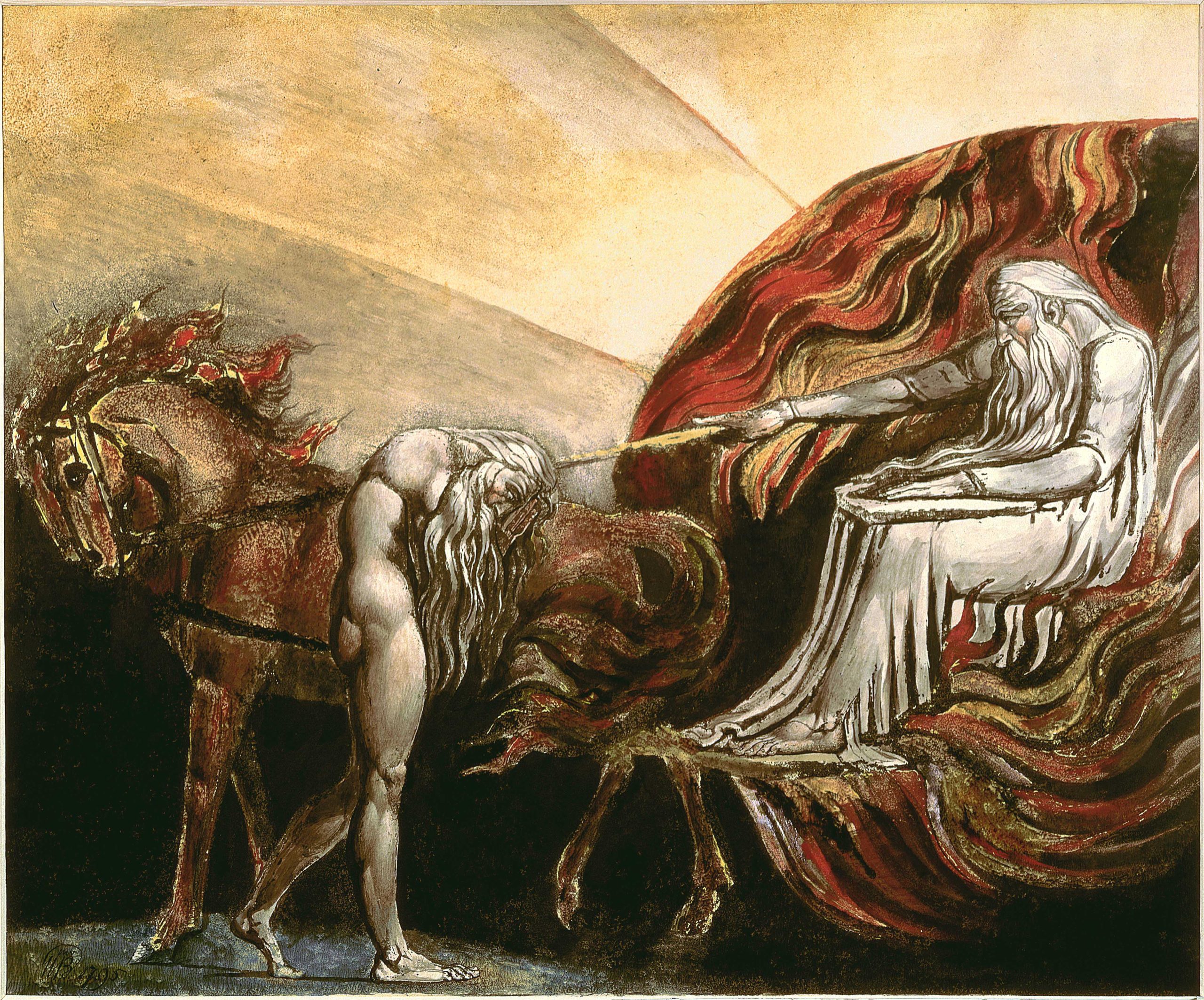

Hegel

The birth of a black hole of betrayal and infidelity. A cosmic blackout.

The curse of the long loneliness

One of Adam’s tasks was to name the animals. (Listen! The river of language is about to change direction.) “Out of the ground the Lord God formed every beast of the field and every fowl of the air and brought them unto Adam to see what he would call them.”[1]

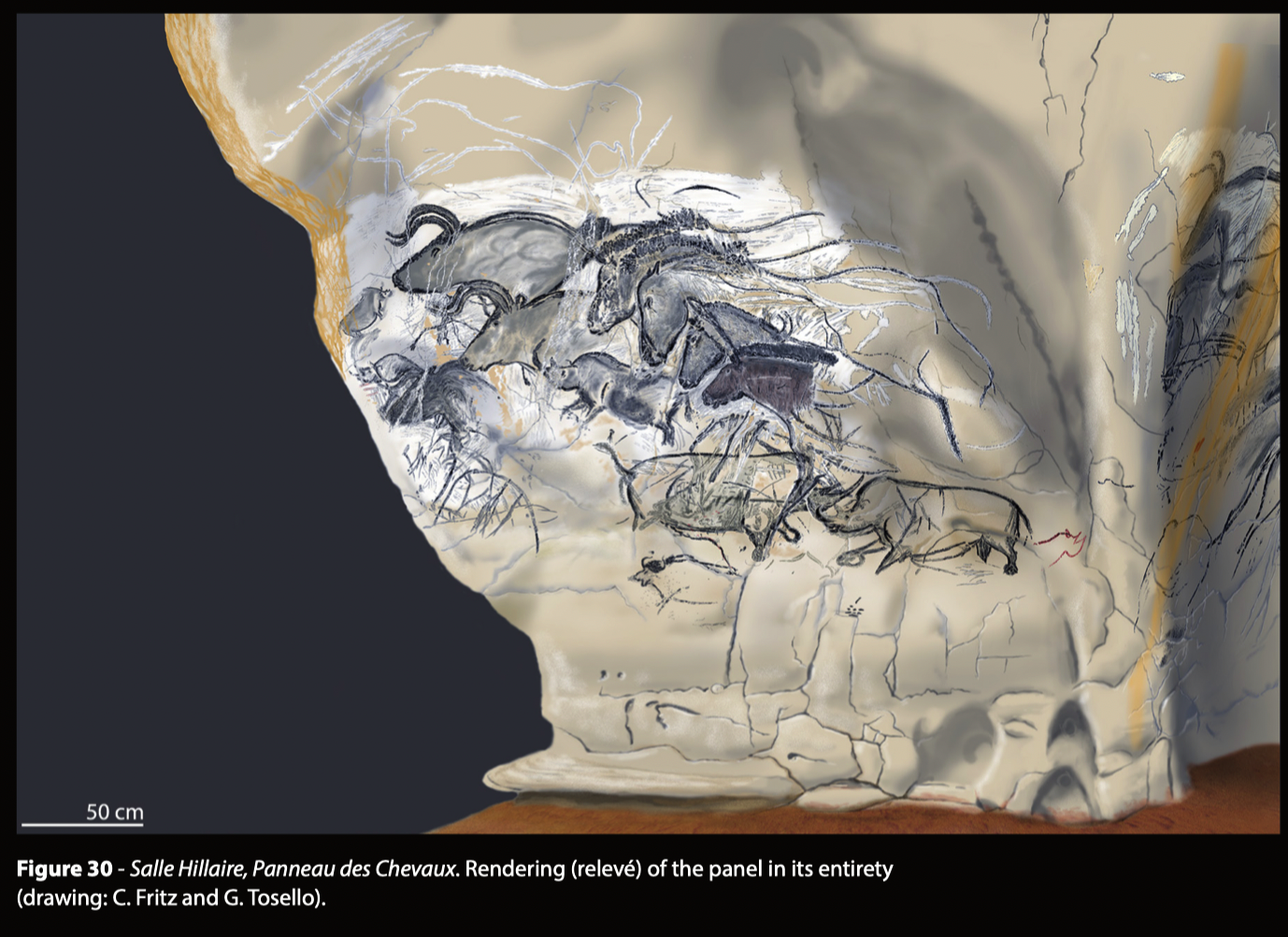

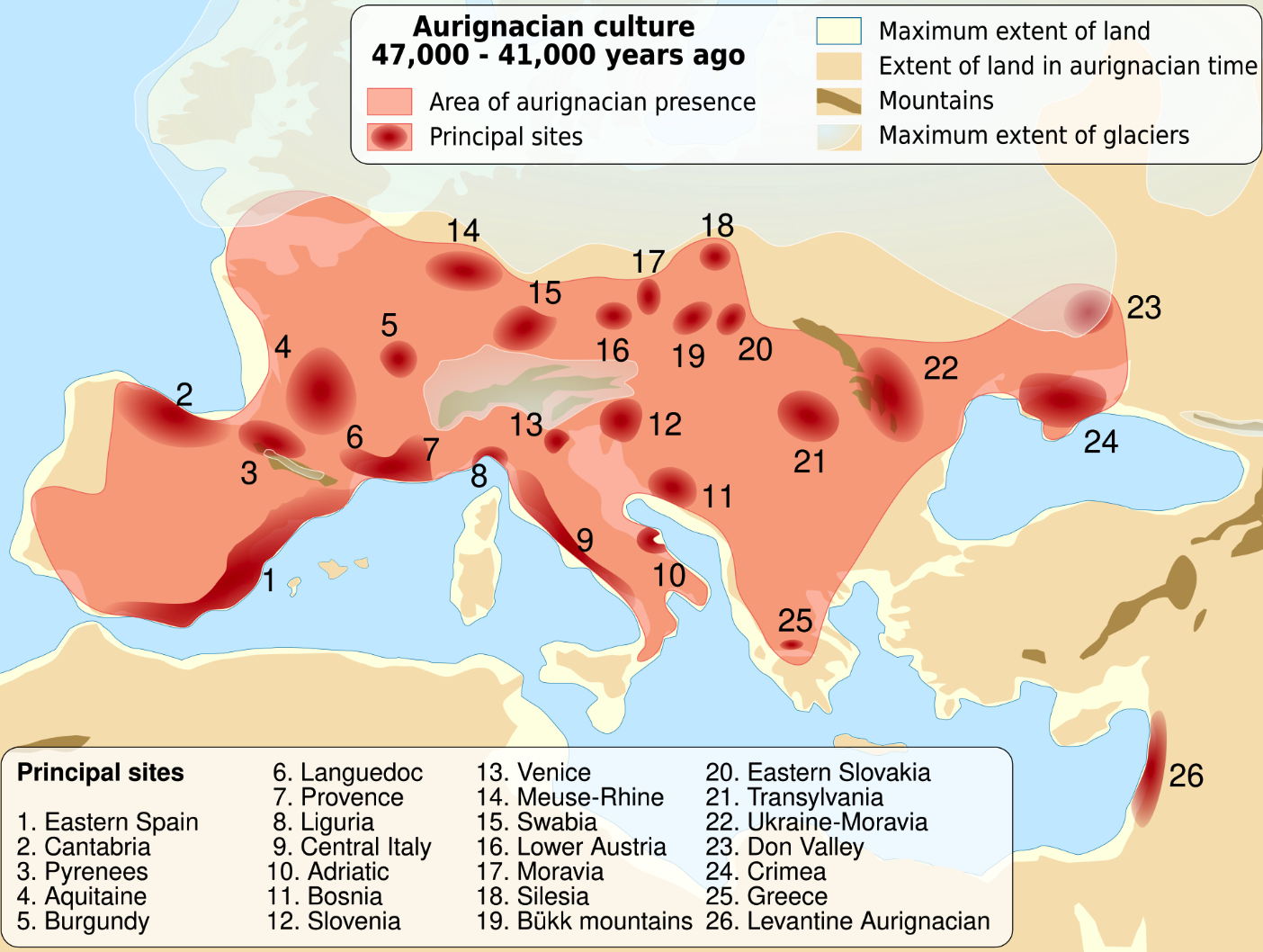

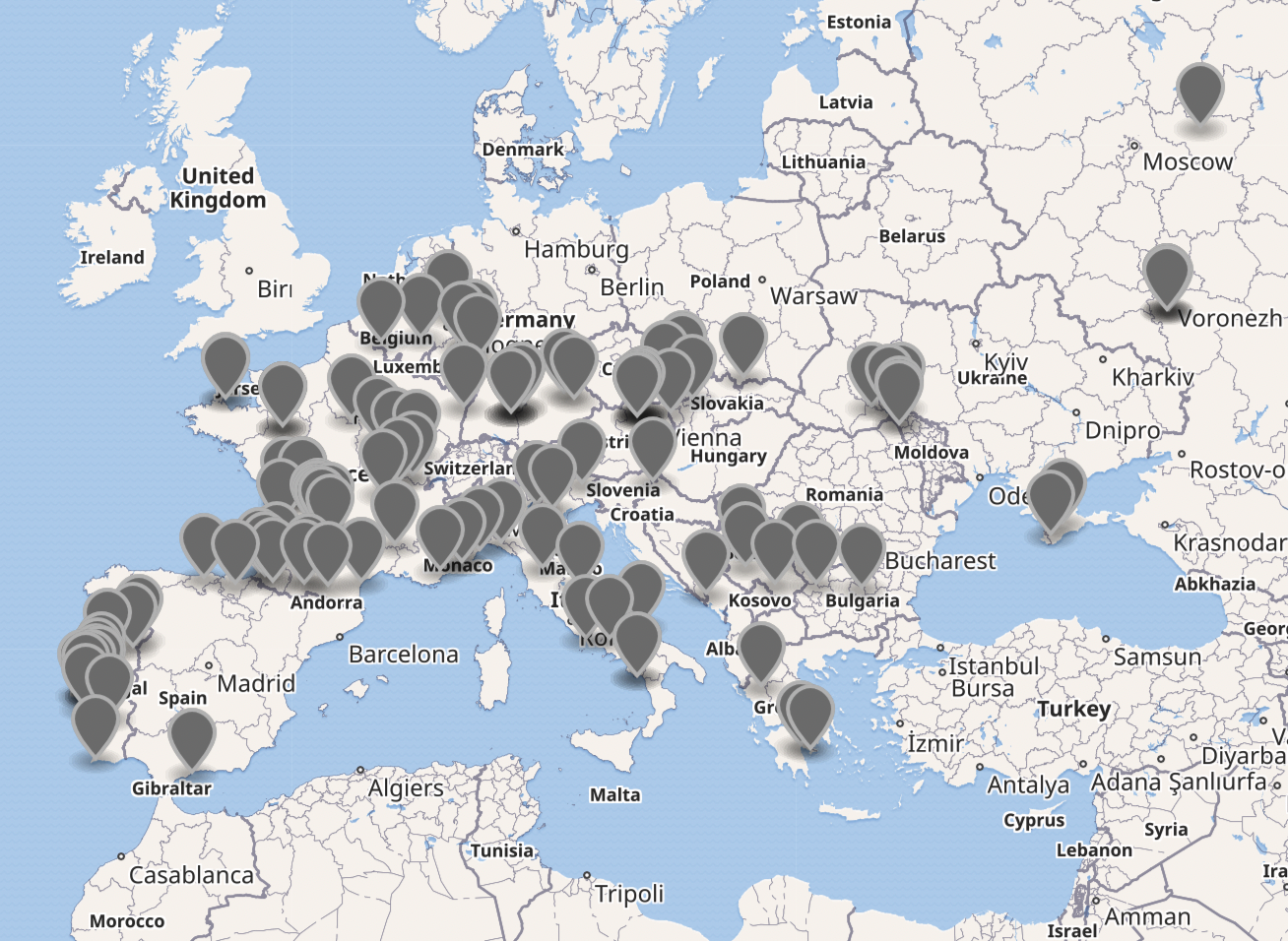

We must place Adam’s seismic achievement within the context of the yardstick. Tens of thousands of years before there is a Lord God and Adam (’ᾰdāmâ), his name-calling lackey, disporting themselves in a Mesopotamian garden of delight, the wild things have vaporously emerged through membranes of stone and exploded upon human consciousness in subterranean galleries, passages, and corridors of dripping limestone. (I refer to Chauvet, Cosquer, Gargas, Pech-Merle, Cougnac, Altamira, Lascaux, Trois-Freres, Roc-aux-Sorciers, La Mairie, and now the 51,200-year-old site of Leang Karampuang in Indonesia.) We can no longer ignore this event or its implications by dismissing it as prehistory, as with Chesterton´s smart-aleck line, ‟Science knows nothing whatever about prehistoric man; for the excellent reason that he is pre-historic.”[2] This is rather like saying science knows nothing whatever about the Pleistocene for the excellent reason that it is prehistoric.

Mr. Chesterton, there is no prehistory; everything about mankind since Lucy the Australopithecine is on the table. Everything is still with us, either wired into our brain or paraded as vesture we call ‟culture.” Nothing got lost along the way; nothing tossed in the dustbin of history of human development or whatever other phony substitute for reality one may wish to put forward. Besides—and this is key—the science you are so fond of was an invention of a barrister, Francis Bacon, who fatally corrupted the word with an odiously legal will to power.[3] (Thomas Carlyle, a mathematician by training, recognized this and denounced it with a barbed reference to Bacon´s ‟attorney logic.”[4] Goethe, who considered himself an uncorrupted, genuine scientist, likewise trashed the will to power intrinsic to science, especially mathematics and physics.[5] By all accounts a mild-mannered, genial man who readily entertained differences of opinion, Goethe despised Newton, excoriating him for his approach to the natural philosophy that we now call physics.[6])

Allow me to pursue this brief against science further, since Chauvet and all the similar sites before and after, whether open-air or in caves (hereafter collectively referred to as Chauvet et al.), demand it. Scientists like to pretend that their discipline has nothing to do with God and religion. What they don´t grasp is that the chief architect and apostle of the so-called scientific method and scientific outlook, Francis Bacon, founded his method and outlook and what we might call the Great Scientific Commission (‟Go ye into all the world and preach the Gospel of Science”) on—listen carefully—the ‟great restoration” of Jehovah’s commandment to agrarian man (’ᾰdāmâ) to exert ‟dominion over the universe.” It´s pointless and disingenuous to argue that Bacon´s Great Commission (my term, not his) became secularized (divorced from the deity) over subsequent centuries. For, prior to the cosmic ‟sky” gods,[7] all of whom were invented by humans brainwashed by the agrarian imperative (’ᾰdāmâ and whatever other names the first systematic farmers went by), there was absolutely no motive or reason or evidence for a paradigm of dominion over the universe or any part thereof.

Why? One could adduce a number of cogent reasons, but the most fundamental of all, the most critical of all, is that there was no Great Dichotomy. No subject-object split. There was no Other. There was no battle good v. evil. One might go so far as to say there was no ego, be it God´s ego or mine or yours. Descartes´s (and Aristotle´s) res cogitans and res extensa quite simply, yet emphatically, did not and could not exist in that pre-Adamic, pre-agrarian, pre-sky god realm. I have called that realm the Pangaea of Wildness. I could just as correctly have called it the Pangaea of Symmetry.

Chauvet et al. give us a stunning glimpse into this non-dual realm, a realm magnificently explained by Neoplatonism. Neoplatonism has not a speck of duality. Neither does Sanskrit philosophy. And therein lies their genius, their brilliance, and their value for us moderns.

What I have said about science applies as well to historical consciousness. It, too, is an invention of the agrarian imperative. Our modern concept of space and time both derive from the Neolithic.[8] In the case of time: history has a starting point, with the Hellenes in Greece or Adam in the Garden or fully formed humans in the Mayan Popol Vuh[9] or what have you. In all cases the People of History and Time (see Maya) are chosen by the gods (or later, in more secular times, by Providence) as set apart from wildness (aka chaos) and anything else the agrarian proposition wishes to control. ‟The word istoria (enquiry),” explains Socrates in the Cratylus, ‟bears upon the face of it the stopping (istanai) of the stream.”[10] The stopping of motion, of movement. History (istoria) indeed has a beginning and end point, a stopping of the stream. Its end point for the religious-minded being a final judgment linked to the annihilation of the world, a final redemption and triumph of good over evil, a glorious fantasy of mankind living eternally in a garden of delight—heaven, if you like. Thus history—what we might call non-scientific history—is an arrow, a vector, on a mission. A trajectory of cleansing or victory over evil or, in Bacon´s over-heated language, overcoming ‟the immeasurable helplessness and poverty of the human race.”[11]

Consider the so-called scientific history of this ‟terraqueous globe,”[12] which has come into increasing fashion since the geological and evolutionary discoveries and theories of the 19th century. Even this perspective on the earth is founded foursquare on the subject-object dichotomy outlined above—and therein lies a deep epistemological problem. Whether we´re dealing with cultural history or scientific history, everything about the earth is outside of us and subject to our control. Increasingly since the turn of the 19th century, it is subject to our control as good scientific stewards (witness the meeting between the Alaska Fish & Game biologists and the Yup´ik elders), or is beyond our control as we ride, like galactic passengers, from the ‟fire-creation of the world to its fire-consummation.”[13]

Let me put it this way—emphatically, categorically, bluntly. As blunt as Bacon was when he trashed Aristotle and Plato (neither of whom he understood),[14] and Nietzsche was when he trashed St. Paul (whom he did understand).[15] No human ideology with the word ‟history” attached to it is worth a damn when it comes to Chauvet et al. Get rid of the word.

If you´re thinking Chauvet et al. can be understood by anthropology, think again. The very word betrays its mission. ‟I mean to say,” again explains Socrates, ‟that the word ‘man’ [anthropos] implies that other animals never examine, or consider, or look up at what they see, but that man not only sees (opope) but considers and looks up at that which he sees, and hence he alone of all animals is rightly anthropos, meaning anathron a opopen.”[16] For a vivid and stomach-churning illustration of the anthropological approach, witness that bull, Franz Boas, in the china closet of the Northwest Coast in the 1880s and 90s. (I treat Boas in detail in a later lecture.)

Chauvet et al. is an epiphany for us moderns. Stop thinking of them as prehistoric sites. Stop thinking of them as archaeology or anthropology or museums or art. They are a revelation of the Logos. Call it the Paleolithic Logos, if you like. What is arresting about these sites, which occur in numerous parts of the world, is not so much the creation of wild things—for, indeed, wild things had been around at least as long as the earliest hominids—but what may be a new level of human consciousness. All is dramatically fluid—movement and motion—at these nodes of rendezvous, globally memorialized in caves and plein air sites. All is potential. All is “presence.”

In the absence of the farming (’ᾰdāmâ) imperative, there is no Baconian ‟will to power” between man-the-hunter and these, his kinsmen. Antedating the ‟will to power” comes the all-important, enabling Aristotelian and, later, Cartesian subject-object dichotomy. The reason there is no whiff of Bacon or Descartes at Chauvet et al. is because the Paleolithic Logos, if I may be permitted to stretch the meaning of this charged and ever mysterious Greek term, was incapable of accommodating either heresy.

In their emergence, the wild things are seen by mankind, and mankind in turn is seen by the wild things [see Socrates, above]. “Sometimes they were people and other times animals, and there was no difference.”[17] In the voice of an Inuit woman we hear the Logos betrayed by Adam. Only against this backdrop can we properly appreciate Adam’s treasonous act. ’Ādām, first agrarian man, finds himself caught between two massive continental plates now beginning to move in opposite directions. The tension between wild and domesticated is tremendous. Literally untenable.

Adam’s god screams at him to name the animals. It is modern man’s defining moment.

Behold the fall. For hundreds of thousands of years language and its parent, consciousness, had flowed from loose-limbed, undulating wildness, moving like a flickering flame across rock walls and open-air boulders, moving like a Dark One in the early snow of Yellowstone Park. Like hydrostatic pressure carving the chambers of the embryonic heart, language and consciousness welled up within the womb of wildness to carve the mind of man.

Keith Basso witnessed this the day he blurted out to an elderly Apache, “What is wisdom?”

Dudley [Patterson] greets my query with a faintly startled look that recedes into a quizzical expression I have not seen before. “It’s in these places,” he says. “Wisdom sits in places.”

This makes no sense to the anthropologist. “Yes, but what is it?”

This time the man says nothing. He merely removes his hat, “rests it on his lap and gazes into the distance. As he continues to look away, the suspicion grows that I have offended him, that my question about wisdom has exceeded the limits of propriety and taste.”[19]

Several minutes tick by. The conversation shifts to other topics. But the old man hasn’t forgotten the question. “Wisdom sits in places,” he ventures once more. “It’s like water that never dries up. You need to drink water to stay alive, don’t you? Well, you also need to drink from places. You must remember everything about them. You must learn their names. . . . Then your mind will become smoother and smoother. . . . You will walk a long way and live a long time. You will be wise. People will respect you.”[20]

Names make your mind smoother. They keep you alive. Names like Tséé Łigai Dah Sidilé, “White rocks lie above in a compact cluster”; Tséé Biká’ Tú Yaahilįné, “Water flows down on a succession of flat rocks”; T’iis Bitł’áh Tú ̛̛ʼOlįné, “Water flows inward under a cottonwood tree”; Tséé Hadigaiyé, “Line of white rocks extends up and out.”[21]

“The names of all these places are good,” affirms Nick Thompson. “They make you remember how to live right, so you want to replace yourself again.”[22]

Something strange transpires here. Basso is pinging another dimension of knowledge. “What sort of reasoning supports the assertion that ‘wisdom sits in places’? Or that ‘wisdom is like water’? Or that ‘drinking from places,’ whatever that is, requires knowledge of place-names and stories of past events?” Maybe, the suspicion grows in Basso, “I have gotten in over my head.” Dudley Patterson’s lecture on wisdom “caught me off guard and has left me feeling unmoored. For a split second I imagine myself a small uprooted plant bouncing crazily through the air on a whirlwind made of ancient Apache tropes.”[23]

Tropes, Professor Basso? You think these people are talking in figures of speech, do you? How about when Annie Peaches (age seventy-seven in 1978) further confounds you with: “The land is always stalking people. The land makes people live right. The land looks after us”?[24]

Truth be told, Professor Basso doesn’t know what to make of this species of language. He confesses he’s stumped—and that’s the mark of a good scholar. “Are these claims structured in metaphorical terms,” he wonders aloud, “or are they . . . somehow to be interpreted literally?”[25]

“She glided beautifully along,” a San woman is quietly telling an American with a notepad.[26] We are standing in a parched village in the Kalahari Desert, eavesdropping on ethnologist Megan Biesele as she interviews a woman about Python Woman. Python Woman, G!kon//’amdima, happens to be the beautiful, sensual daughter-in-law of the creator Kaoxa. It would not be too much of a stretch to call her the Bushman equivalent of the biblical Eve crossed with the Virgin Mary. Like the Blessed Virgin among the devout, G!kon//’amdima is considered the ideal woman, and very real.

“She glided beautifully along and sat down,” the woman is saying, “because she was a person, an elephant girl. Because a python is an elephant.”[27]

Something isn’t right here. What we just heard is nonsense. “How can that be?” objects Biesele. “I thought a python was one thing and an elephant was another thing!” (Listen! The river of language is about to be restored to its original direction.) “Yes, that’s true,” cheerfully agrees the woman, “but people say that a python is an elephant anyway.”[28]

Basso and Biesele bear witness to another realm of language and names. Where language and names sit in places, a conscious, sentient story resides there. Where G!kon//’amdima is not just Python Woman and Elephant Girl but also Beautiful Antbear Woman and Human Maiden, and, for her final showstopper, she transforms into steenbok—an eerily fluid identity, as if category boundaries have been suspended or simply don’t exist.

Recall /haṅǂkass’ō’s distress on discovering that in Lucy Lloyd’s Logos, it was perfectly reasonable to “throw away” a fungus. In /haṅǂkass’ō’s ontology, this was not a clear-cut, isolated object but a smear of probability—a force field of wind, rain, storm, and who knows what else momentarily converging within this serene presence best called, after all, a “rain’s thing.” Vague, full of potential. Energy, after all.

Was not the prudent course to put this ravishing, breathing, sentient energy “gently down”?[29]

Before the invention of ’ᾰdāmâ, Logos had no name. How could it? Just a vague phrase. Adam, the farmer, trapped and bound it within a name. Caught in the shearing forces of wild versus domesticated, Adam survived by giving every living thing a name. To this day we, his cultural heirs, have not stopped. “And whatsoever Adam called every living creature, that was the name thereof.”[30]

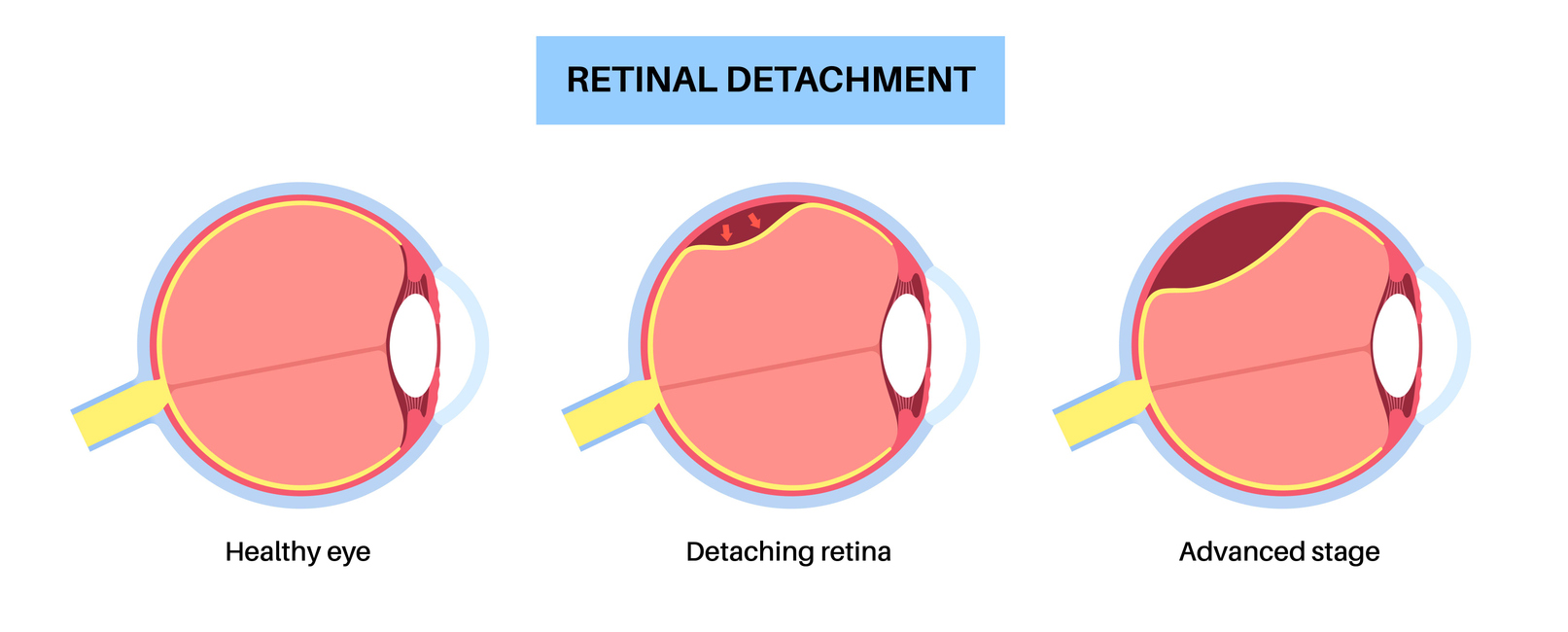

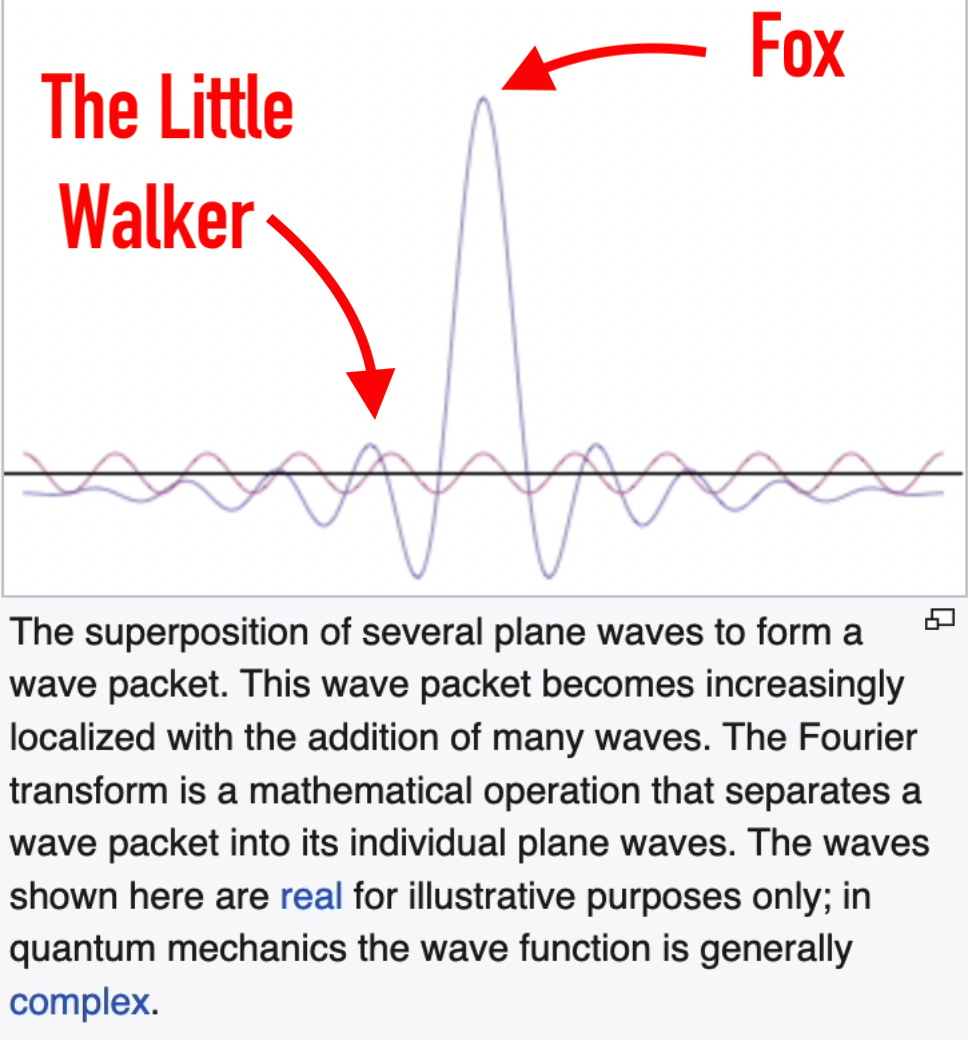

Think of the new Yahwist Logos as a retina detaching from the vascularized choroid of the world, to become, paraphrasing Gerald Bruns, necrotic and dangerously isolated.[31]

On that day totemism vanished from consciousness, just as it fled Enkidu the hour he became “aware of himself.”[32] Imagine this chthonic consciousness as the “distant heart” Rilke refers to:

Who sings the distant heart

that dwells whole at the core of all things?

Its great pulse is parceled out among us

into tiny beatings. And its great pain

is, like its great jubilation, too much for us.

So again and again we tear ourselves loose

and are only mouth. But all at once

the great heartbeat secretly breaks in on us

so that we scream . . .

and then are being, transformation, visage.[33]

Who speaks the Logos that dwells whole at the core of all things? Enkidu did. So did Paul John (Kangrilnguq) in the room full of fish and game managers. So do we all when we are children. I must emphasize this. Its pulse is woven into us deep and magical.[34]

Seen against this background, the new Yahwist Logos was more truly a counter-Logos, since it flowed in the wrong direction. I am not the first to point this out; Hegel said as much in his 1803–4 Jena lectures, pointed out above. When Adam named the animals, “he annihilated them as beings.”[35] “In that guttural achievement,” borrowing a passage from the anthropologist Loren Eiseley, Adam “had created his destiny and taken leave of his kindred. There would be no way of return, save perhaps one: through the power of imaginative insight, which has been manifested among a few great naturalists.”*[36]

Nearly two centuries later, Nobel laureate J. M. Coetzee unpacked Hegel’s cryptic observation. Coetzee does so through the voice of the fictional alter ego referred to earlier, Elizabeth Costello, who in this scene compares Rilke’s “Panther” to Ted Hughes’s “Jaguar” and “Second Glance at a Jaguar.”[37] “When we divert the current of feeling that flows between ourself and the [caged, wild] animal into words,” she explains to her seminar audience, “we abstract it forever from the animal. Thus the poem [when it is merely descriptive of the animal] is not a gift to its object, as the love poem is. It falls within an entirely human economy in which the animal has no share.”[38]

Coetzee’s “current of feeling” between us and the animal and Rilke’s “distant heart at the core of all things” are, for Wallace Stevens, “the essential poem at the centre of things”;[39] three visions of the supercontinent of consciousness I refer to as the Pangaea of wildness, the universal intercourse Paul John (kangilngaq) and Charlie Kilangak (qilangaq) [40] still participated in, albeit tenuously, as did the Apache Dudley Patterson, the San /haṅǂkass’ō, and Megan Biesele’s Ju/’hoansi storytellers.

It is “as if the central poem became the world, / and the world the central poem,” writes Stevens, carefully taking soundings while peering through the fogbank that, since Adam, has hidden this supercontinent from Western consciousness.[41] “We seek,” he probes further,

The poem of pure reality, untouched

By trope or deviation, straight to the word,

Straight to the transfixing object, to the object

At the exactest point at which it is itself,

Transfixing by being purely what it is.[42]

Here is where things get weird. The poem of pure reality takes us, in fact, to something unconstrained by space and time, something implicit rather than discrete and explicit. Something that is better thought of as a process of enfolding and unfolding.

Consider Knud Rasmussen’s field notes from the Fifth Thule Expedition, where he painstakingly writes down a series of ancient shamanic words whispered by the Netsilik Eskimo, Orpingalik, who we met earlier.

Despite being born to an Eskimo and speaking her language, Rasmussen finds many of Orpingalik’s words and phrases unintelligible, verbal flotsam and jetsam cast up by the oceanic Logos of Sedna’s world—the world of shamans lowering themselves through a hole in the ice to comb the tangled hair of the Keeper of Walrus and Seal, a world Rasmussen finds is growing increasingly remote and opaque, unable to withstand the countercurrent of rifles, scripture, sewing needles and shiny thimbles, and tuberculosis. The ancient totemic retina is becoming unstitched.

This is what Rasmussen recorded in his notebooks. (I have omitted the Netsilik words; these are the literal English translations of what Rasmussen termed “shaman” words.)

the jumper

the little walker

one who walks with his head bent down

the penetrating one

the flat one

the one who snorts loudly

the little one furnished with fangs

the one furnished with fangs

that which looks warm

the hovering ones

the one that gives soup[43]

Something compels us to go over the list again, as if we missed something. Perhaps the murkiness of the phrases testifies to an ancient world going blind?

No. We missed nothing. The Logos of wildness is always this way. Yet the state we call ambiguity is not in play. Take, for example, pisuk·a·ciaq (I have no idea how it’s pronounced), which translates literally as “the little walker.” In the margin, Rasmussen scribbles the word “fox.” (In fact, he performs this editorial operation on all of the phrases, believing that he is clarifying what each refers to.)

Thus, pisuk·a·ciaq = the little walker = fox. Except, Rasmussen isn’t certain of his translations. “Translating magic words is a most difficult matter,” he confesses, “because they often consist of untranslatable compounds of words, or fragments that are supposed to have their strength in their mysteriousness or in the very manner in which the words are coupled together.”[44]

Rasmussen is onto something, something hinted at in the next line: “But as every magic word has its particular mission, it is considered . . . immaterial whether it is understood by humans or not,” followed significantly with “as long as the spirits know what it is one wants.”[45]

Had Rasmussen consulted the German philosopher Martin Heidegger before appending his interpretations, he might have had his misgivings confirmed: shamanic words cannot be rendered into an object “at the exactest point at which it is itself.”[46] A century after Rasmussen, we can confidently say there is no exact point at which the Logos invoked by Orpingalik is itself.

Consider Heidegger. “Language alone brings beings as beings into the open for the first time. . . . Language, by naming beings for the first time, first brings beings to word and to appearance. Only this naming nominates beings to their Being from out of their Being. Such saying is a projecting of clearing, in which announcement is made of what it is that beings come into the open as. Projecting is the release of a throw [as in throwing a ball] by which unconcealment infuses itself into beings as such. This projective announcement forthwith becomes a renunciation of all the dim confusion in which a being veils and withdraws itself.”[47]

Heidegger struggles vainly for clarity and precision; the subject, like the electron of quantum physics, lies in a reality beyond the reach of modern discursive language, founded foursquare on the will to control. The novelist J. M. Coetzee, a mathematician by training, fails for the same reason in the exhortations and hectoring of Elizabeth Costello.

Unlike the biblical Adam and Rasmussen, Adam’s intellectual heir, Orpingalik did not name a creature. In fact he was not trying to name a creature! He invoked, instead, what physicists call a field theory of possibility.

Dudley Patterson’s “White rocks lie above in a compact cluster” derives from the same Logos wherein “the little walker,” “a rain’s thing,” and “a python is an elephant” thrive and bestow their gifts on us.

In the Logos of wildness, pisuk·a·ciaq = the little walker ≠ fox! In this pre-Adamic realm, pisuk·a·ciaq is capable of being anywhere (it possesses nonlocality) and anything (it is plenipotent).

The same principles underpin the world of quantum physics. Nobel laureates tell us that subatomic matter, such as electrons, exist in all possible places and all possible forms at once, not unlike the Bushman’s “rain’s thing.” Only by an act of measurement (the operative word) do electrons, photons, and other forms of subatomic matter or energy become frozen into a single observable state, not unlike the linguist’s “fungus.”

Physicists have a name for this eerie omnipresence and plenipotentiality; they call it superposition.[48] Click here for a video “visualization” of superposition. (Werner Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle and Niels Bohr’s complementarity principle were early expressions of superposition.)

We have entered the world of Alice in Quantum Wonderland. Whereas Lewis Carroll’s story is fantasy, this one is not. (Whether quantum reality squares with our convictions or intuition of how the world works, of cause and effect, of before and after, matters not one whit. Physicists assure us that quantum reality is the real reality. Yes, they may debate details, such as whether electrons are both particles and waves or more like the vibrating strings of a violin, but few dispute its basic principles as demonstrated by the double-slit experiment and the solid evidence for nonlocality, as I discuss in the next lecture.)

The further we travel down the rabbit hole of theoretical physics, the curiouser and curiouser things become. Physicists know that the captured behavior of this endlessly transfiguring renegade, this eternally unfathomable elementary particle, the electron, is profoundly influenced by the observer—that is, whoever happens to be evaluating the performance of that particle with an instrument of any sort. Bizarre as it sounds, the instrument of measurement might be merely a thought. A word. A phrase.

Quantum reality and the reality of wildness are two halves of the same coin, I have come to believe. Indeed I suspect wildness is but another name for quantum reality operating at the level of human experience, human phenomenology. The key is the untouchable, impenetrable, impalpable uncertainty that informs both the quantum world and the place where the wild things are, to borrow a phrase from Maurice Sendak.

Where the Wild Things Are is classic Sendak: disturbing, provocatively illustrated, and brilliant. Like his other stories, the tale is so short you could copy it out on the back of an envelope. It’s about young Max, who dressed up in his wolf suit one evening and “made mischief of one kind and another.” Sent to bed without supper, the unrepentant Max (still in wolf costume) finds himself tumbling through a quantum rabbit hole into the realm where the wild things dwell—the ambiguous monsters of childhood. Totemic Max is ecstatic. “And now,” he exclaims, “let the wild rumpus start!”

Max is right. Anyone who plunges into quantum physics or wildness is in for a wild rumpus. There’s no better place to begin than the living room of a physicist named Lothar Wolfgang Nordheim.

This is a true story. Hang on tight. Professor Nordheim and his wife have just finished entertaining a dozen guests for dinner, and they’re all sitting around the drawing room chatting amiably (the men possibly smoking cigars). They decide to play a variant on the silly old parlor game Twenty Questions. In this version, one person leaves the room while the rest choose a single word, which the person who is It must guess upon reentering. The interrogator is allowed just twenty questions, whereupon they must hazard a guess at the word. The people in the room reply to any of the twenty questions with only a yes or no.

What was noteworthy about this particular game was the people playing it. Several were theoretical physicists, including Edward Teller, father of the hydrogen bomb, and Princeton’s John Archibald Wheeler. When Professor Wheeler’s turn came, he recalled years later, they took an awfully long time to call him back. When they finally did, he noticed that everyone was grinning.

However, I went ahead innocently asking my questions. “Is it animal?” “No.” “Is it vegetable?” “No.” “Is it mineral?” “Yes.” “Is it green?” “No.” “Is it white?” “Yes.”

As I went on with my queries I found the answerer was taking longer and longer to respond. He would think and think. Why? That was beyond my understanding when all I wanted was a simple yes or no answer. But finally, I knew, I had to chance it, propose a definite word. “Is it cloud?” I asked. My friend thought for a minute. “Yes,” he said, finally. Then everyone burst out laughing.[49]

Wheeler included the story in his opening lecture at the seventeenth Nobel Conference in 1981, “Bohr, Einstein, and the Strange Lesson of the Quantum.” He used it to illustrate how we live in what he called a participatory universe: how we literally shape reality by the questions we put to the universe.

Wheeler entered a room where the dial of reality had been reset according to quantum principles: there was no word in the room, just a seamless consciousness of every possible word. His dinner companions had reversed the conventional epistemology:

I, entering, thought the room contained a definite word. In actuality the word was developed step by step through the questions I raised, as the information about the electron is brought into being by the experiment that the observer chooses to make; that is, by the kind of registering equipment that he puts into place. Had I asked different questions, or the same questions in a different order, I would have ended up with a different word, as the experimenter would have ended up with a different story for the doings of the electron.[50]

Match this with what I am calling the language of wildness. When Wheeler summoned the word cloud into being out of the flux of endless possibility, everyone in the room laughed. When Adam called the word for each animal into being out of the flux of endless possibility, he canceled something crucial about their being, as Hegel pointed out. The jumper, little walker, the one who walks with his head bent down, penetrating one, flat one, one who snorts loudly, little one furnished with fangs, one furnished with fangs, and the one that gives soup—poof!—disappeared, to be replaced by something not quite the same: fox, caribou, moose, and so on. They vanished because Adam, unlike Wheeler, occupied a chamber thick with totemic consciousness.

Convergent consciousness, the ancient, flawless sheet of glass, shattered when Adam awakened the genie known to physics as the problem of measurement.[51] All that remained was a special case of little walker we call fox, whose mind and consciousness were now forever estranged from us.

Alaska state biologist Randy Kacyon tacitly acknowledged the estrangement when he broached the subject of moose (tuntuvak[52]) at the biannual meeting of the Y-K Delta Subsistence Regional Council described in the first lecture. I said Kacyon was reprimanded by a Yup’ik elder from Toksook Bay named Paul John. Let me amend this to say that on the axis of wildness, Kacyon was rebuked by a kangilngaq.

In the first lecture I gave Paul John’s Yup’ik name as Kangrilnguq, which is a denatured version of the phrase kangilngaq. The Alaska Native Language Center’s Yup’ik Eskimo Dictionary translates kangilngaq as fox.[53] Likewise, the name (Charlie) Kilangak is a version of the phrase qilangaq, which the same dictionary translates as puffin.[54]

The dictionary’s definitions are reminiscent of Rasmussen’s interpolations, where pisuk·a·ciaq = fox. Rasmussen and the compilers of the Yup’ik Eskimo Dictionary are correct only within a Cartesian and Newtonian, or Adamic, frame of reference. While writing these lectures it dawned on me that kangilngaq and qilangaq are more properly expressions of a field theory of potential within the implicate order of that uncanny landscape. When qilangaq handed me the slip of paper with “I am puffin” penciled at the top, he was summoning a state that can be experienced only within the quantum potential.

By the transformative powers of language, Adam and his offspring, among them Rasmussen and the compilers of the Yup’ik Eskimo Dictionary, recast something existing along one axis of fact (little walker) into something now existing along a different axis of fact (fox). What we perceive as fox, moose, puffin, etc., is more properly the end point of an event we participate in creating. “All that’s named is past and each being / invents itself at the last second / and will hear nothing”[55]; Rilke’s lines could have been written by John Wheeler or Wheeler’s former Princeton colleague, David Bohm, whom we will encounter in the next lecture.

For centuries indigenous people have been trying to explain this process to people like Megan Biesele, sitting cross-legged in the dirt, finding herself forced to choose between two crosscurrents of fact. Both real, mind you, both there; neither one fiction or fantasy, each accessed through language. Above all, I repeat, through language.

Along the axis of wildness practiced by her hosts, the ethnologist discovers that python and elephant are a distinction without a difference. This does not match Biesele’s Western axis of reality, on which python and elephant are two absolutely separate and distinct creatures, related only in the irretrievable evolutionary past—in what we call the archeological record.

To her credit, Biesele suspends her cultural axis-of-fact and enters into the joy of mankind’s oldest conversation. “I felt there was a kind of luminous equivalence—that is the only way I can put it—about the attitudes held toward the physical beings of these animals in their roles as heroines.”[56]

I believe we can make a quantum leap beyond Biesele’s notion of luminous equivalence. Along the San axis of reality, python, elephant, antbear, human, and steenbok exist in superposition, which is another way of saying they exist in wildness. Reading between the lines of Biesele’s field notes, the San appear to know that objects “ain’t nothin’ until I calls ’em.” (At the close of his Nobel Conference lecture, Wheeler asked his audience to picture three umpires relaxing over a beer in a barroom. “One umpire says, ‘I calls ’em as I sees ’em.’ The next umpire says, ‘I calls ’em as they really are.’ The third one says, ‘They ain’t nothin’ until I calls ’em.’ ”[57])

Using the game of musical chairs as an analogy, things ain’t nothin’ until one stops the music, thereby capturing wildness in a discrete, often animal form—whereupon it ceases to be wildness. Or does it? The next chapter should shed some light on this interesting question. As we shall see, the issue of whether the discrete animal form is or is not in a state of wildness may depend on the observer. (Be that as it may, Rilke describes the process as “duration squeezed from transience.”[58])

What’s arresting about the San woman’s narrative is that she speaks as if the music is always playing: “People say that a python is an elephant.” Indeed, during the course of her interviews Biesele discovers that, generally speaking, the San refrain from calling ’em. The result being, to invoke Wheeler’s phrase once more, they ain’t nothin. (Which, as I say, is another way of saying they are everything. They remain part of the “unnamed shifting architecture of the universe,” Eiseley called it.[59])

“Speech,” “tree-water,” “sand surface,” “fire medicine,” and “soft throat”: Biesele found hundreds of these words and phrases. It is interesting that she called them “respect words”: “Ordinary implements, parts of the face and body, items of clothing, huts, encampments, areas of land—all have respect words associated with them.” So many, in fact, that they form “almost a second language.”

Working on these words one day with informants, I asked for the respect terms for various animals. We began with carnivores. The terms for these were given as I asked for them. When we got to the great meat animals, however, I no longer needed to ask. The respect words for these were reeled off in rapid succession, in a kind of litany form I had heard used previously for the meat animals’ regular names.[60]

Frank Speck encountered the same ancient language among the eastern subarctic Naskapi (northern Québec-Labrador) in the 1920s: “black food” (bear), “the one who owns the chin” (bear), “short tail” (bear), “his great food” (bear), “great food” (bear), “grandfather” (bear), “big hard back” (turtle), “spirit fish” (smelt), “different songs for animals,” etc.[61]

A century before Speck, the German ethnographer and director of the Russian-American Company, Ferdinand von Wrangel, compiled a list of over 300 Yup’ik Eskimo terms from the Kuskokwim River region, a good many of which are not used now, tellingly notes the Yup’ik Eskimo Dictionary. One being the phrase erinatuli, “one with a big voice”—a sandhill crane, reads the dictionary.[62]

The dictionary is wrong; “one with a big voice” exists in a different manifold of reality from sandhill crane. The real people of this place knew this. Consider the ornithological notes of Edward Adams, a ship’s surgeon and naturalist who wintered at Michalaski (St. Michael’s), a fortified Russian trading post on Norton Sound near the mouth of the Yukon River, from October 1850 to June 1851. (I spent two winters near this spot in the mid-1990s, occasionally spending a week in Yup’ik villages on the frigid Bering coast.) Adams had signed on the HMS Enterprise, commanded by Sir Richard Collinson, to search for the ill-fated Franklin expedition. “Ardently fond of natural history,” recalled a contemporary, Dr. Adams “devoted his leisure hours to its study; and his talents in this respect had an important bearing upon his subsequent [exploratory] appointments.”[63]

By current standards Adams would be considered a professional ornithologist. This makes his field notes especially instructive. What they reveal is that the creature he called a “brown crane” (sandhill crane), for instance, was túds-le-uk. That is, it didn’t have a name; it had language. Running our eye down Adam’s bird list, we discover this is true of virtually all the birds he mentions. They were known to Yup’ik Eskimos by their speech.

In the list below, I present the Eskimo phrase for each bird just as Adams recorded it. There are dozens of these. I have chosen the following pretty much at random. In parentheses I have added Adams’s translation.

chik-a-ki-perc (black-cap titmouse)

jo-lu-kar-nár-uk (American barn-swallow)

pig-git-tig-wuk (Lapland bunting)

e-már-o-slik (snow bunting)

luk-luk (white-fronted goose)

luk-loó-nuk (brant)

ting-a-zó-me-ár (American widgeon)

lub-e-lub-e-lúk-uk, cloo-me-ár (sandpiper)

pe-pé-pe-uk (godwit)

too-oó-slik (northern diver/common loon)

tun-oó-slik (black-throated diver/arctic loon)[64]

Listen to high quality recordings of these bird calls, such as are available online from the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, and it’s immediately apparent the Eskimo phrases were, as I say, the speech of each creature. (Nowadays, we refer to this as the bird call. Since all creatures were thought by Eskimos to be sentient, conscious, intelligent, and able to speak in one or more of their manifestations, I shall use the words speech and language.)

The Yup’ik Eskimo Dictionary calls these Eskimo phrases “imitative.”[65] To invoke mimesis is to miss the point. The phrases recorded by Adams and the host of other European and American travelers to these polar regions, beginning with James Cook in 1778, reveal wildness carving the mind of man. They reveal the river of language flowing in its proper direction. There were no names in the landscape where Edward Adams wandered about with his shotgun and bird list. Like Prof. Wheeler in the game of Twenty Questions, Adams entered a realm where specificity, what Wallace Stevens called “the crust of shape,” was meaningless.[66] There were no cranes, loons, brant, snipe, plovers, dunlin, sandpipers, godwit, terns, kittiwakes, or phalaropes here; just a landscape engaged in full-throated consciousness.

Similarly there were no lions in the Kalahari witnessed by the ethnologist Megan Biesele; just “night,” ” “moonless night,” “night medicine,” “cries in the night,” “calf muscles of nightfall” (or just “calf muscles”), and “jealousy”—each a metaphor for lion, she concluded.[67]

In this she was wrong. “The friendly and flowing savage”—Walt Whitman’s inimitable way of putting it—was not speaking in metaphor as we moderns understand it.[68] The San were invoking the participatory consciousness that suffused the landscape and all that dwelled therein; where the linguistic operators for metaphor, analog, and mimesis are nonexistent, since there is no mind-space separate from Mind at Large, where “everything is everything else, / one long muscle.”[69] In the First World of mankind, contrary to Claude Lévi-Strauss and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, symbols were out of the question and names were pointless.[70]

“When the world first began,” say the Ju/’hoansi, “animals were people, with people’s names,” meaning that animals existed as kudu-people, steenbok-people, eland-people, lion-people, zebra-people, etc., no different from human-people. “The animals had undifferentiated bodies, and in fact were indistinguishable from people.”[71] Recall Nâlungiaq (Netsilik) repeating this nearly verbatim to Knud Rasmussen: “Sometimes they [the animals] were people and other times animals, and there was no difference.”[72]

Then something cataclysmic happened. The linguist Andrea Moro calls it the Big Bang in human consciousness.[73] Listen as a San named Tci!xo N!a’an explains. “Long ago, they [the animal-people noted above] were all sitting around talking together,” he begins. “They talked and discussed things, and they said, ‘Today we’re going to n=om ka n/om [create n/om, inserts Biesele]. Then we’ll write the name of all the animals on their hides. Today we’ll n=om ka n/om, and we’ll use it to give a different design to each animal.’” (Writing the name on the hide involved painting a species-specific pattern on the hide of each creature, as we will see in a moment.) Then comes the bombshell: “‘From today people [animal-people] will no longer be people [animal-people], but will have markings [names] and be [solely, strictly, exclusively] animals.’ So they . . . gave names to all the animals; they told each animal his name. ‘Today we’re going to brand [name] you all, so that you will be [nothing but] animals from this day.’”[74]

All this sounds familiar: the San version of Adam naming the animals. I’ll wager the San re-tooled the biblical story, which their 19th and 20th-century ancestors undoubtedly had drilled into them by missionaries and schoolteachers (who were generally one and the same).[75] Biesele’s version, from which I am quoting, was translated by an unnamed source from a narrative credited to a man named Tci!xo N!a’an from G!oce, Botswana, in 1972.[76] Unfortunately, Biesele does not include a literal, unedited translation. (Perhaps it was unavailable to her.) Be that as it may, the English translator clearly bowdlerized Tci!xo N!a’an’s text, “fixing” ambiguities and incomprehensible phrases, reminiscent of Rasmussen bowdlerizing the phrase pisuk·a·ciaq to mean “fox.” How many corrections—how much undoing—should be made to Tci!xo N!a’an’s text? Corrections like: “the little walker” is not the same as “fox” (pisuk·a·ciaq ≠ fox)? If Rasmussen is a guide, the answer becomes obvious.

In short, the English translation presented by Biesele has almost certainly lost much of its shapeshifting (plenipotential) properties.

Next, we must address the phenomenon of n/om, which is the phenomenological operator in the transformation from animal-people to animals-who-are-not-people. What is n/om? There is no simple answer. It’s like asking what is pisuk·a·ciaq? The best one can say about pisuk·a·ciaq is that speaking the phrase initiated a quantum event that simultaneously changed the speaker and conjured up a presence we erroneously call “fox.” The vital word being “event.” A presence, by the way, which may have been seen or not; the point is that it was summoned out of the implicate order and was now present as the gift—not “fox,” but “gift.”

N/om is likewise inaccessible to language, measurement, and specificity. Biesele calls it “a special kind of energy or spiritual power”—“invisible, dwelling in the n/om songs and in the bodies of the trancers, where it was placed by the great god,” here lying dormant “until it is activated by the singing and dancing.” The god is the creator Kaoxa, “a kind of Lord of the Animals” and source of all n/om.”[77]

To be in the presence of n/om is inevitably to be changed by it. That is, one enters its limitless domain of power where any number of transactions can occur, including healing of the sick, influencing the weather, influencing the game animals, and seeing through time and space. (N/om is the kind of experience Carl Jung would have fled. Recall his memoir where he reprises the chilling question, “What is going to happen to Jung the psychologist in the wilds of Africa?”[78])

“They drew and wrote upon the animals so they all had designs,” continues Tci!xo N!a’an. “Some of them walked away with lovely spotted hides. Some were one way and some were another. There was this one, and that one, and that one.”[79]

Recall Hegel. “The first act whereby Adam constituted his rule over the animals was that he gave them names; that is, he annihilated them as beings.”[80] Recall Heidegger. “Language alone brings beings as beings into the open for the first time. . . . Language, by naming beings for the first time, first brings beings to word and to appearance. Only this naming nominates beings to their Being from out of their Being . . . , in which announcement is made of what it is that beings come into the open as.” Naming, he says, is a “projective announcement”—projection, as in the speaker throwing a ball—“by which unconcealment infuses itself into beings as such. This projective announcement forthwith becomes a renunciation of all the dim confusion in which a being veils and withdraws itself.”[81]

Biesele interprets Tci!xo N!a’an’s story “as a fall from grace.” She calls the story “Branding of the Animals.” She should have called it, “The Naming of the Animals.”[82] “Before the time of this story”—“when the world first began”—let me reiterate that “the animals had undifferentiated bodies, and in fact were indistinguishable from people.” “The animals were people, with people’s names.” After this story, “they had marks to show which animals they were, and [had] species names.”[83]

“From this day,” writes Biesele, “animals are just animals and no longer have human characteristics.”[84] “And whatsoever Adam called every living creature,” echoes the Hebrew bible, “that was the name thereof.”[85] Collectively, their name is now animals-who-are-not-people; that is, “brutes . . . that . . . have no reason at all,” interjects Descartes, who can’t imagine any intelligent person thinking otherwise. “It is nature ,” he insists, “which acts in them according to the disposition of their organs, just as a clock, which is only composed of wheels and weights is able to tell the hours and measure the time.”[86]

Hegel and Heidegger rest their case.

“Right from the start,” muses the linguist Andrea Moro in I Speak, Therefore I Am, “we see that thinking about language is a complicated, stormy, and mysterious business. For now, however, one certainty is clearly striking: however much veiled in mystery, the ability to name things is . . . the real big bang that pertains to us.”[87]

It wasn’t a big bang. A forensic analysis of the Paleolithic reveals the birth of a black hole triggered by the treacherous act of naming within a universal mind-space of mirrored, symmetrical consciousness. A black hole of betrayal and infidelity. A black hole wherein animal-people are banished to the state of animals-who-are-not-people and eventually brutes having no reason at all. A cosmic blackout with repercussions for physics, as I shall explain in the following lectures. Nor was this event a matter of mankind’s ability, Professor Moro; it was a choice, like the biblical Eve choosing to eat the fruit named good and evil.

Witness the catastrophe of Eve’s choice, memorialized in Paradise Lost.

Th’ Almighty thus pronounced his sovran Will

………………………………………………….

To remove him [Adam] I decree,

And send him from the Garden forth to Till

The Ground whence he was taken. . . .

Michael, this my behest have thou in charge

……………………………………………..

Without remorse drive out the sinful Pair [Adam and Eve],

From hallowed ground th’ unholie, and denounce [announce]

To them and to their Progenie from thence

Perpetual banishment.[88]

—John Milton, Paradise Lost

Milton got it wrong. The truth is agrarian man drove the animal-people out of a paradise of shared meaning into a state of domesticated property (livestock) or fugitive wildness (wild beast). Suddenly within the firmament of universal consciousness a chasm appeared, the unthinkable abyss of mankind apart and, with it, the curse of the “long loneliness.”[89]

This is more than loneliness; it is destitution. The man-who-names builds walls within which “only what he hears, one meaning alone,” is heard, “as if the paradise of meaning ceased / To be paradise.” Implacable existential destitution is the new testament.[90] The new hymns are “hero-hymns, . . . hymns of the struggle of the idea of god / And the idea of man.” [91]

It is the greatest propaganda swindle ever confected by mankind.

__________________

Footnotes

[1] Genesis 2:19 (KJV).

[2] Chesterton, ‟Science knows nothing”

[3] See Bacon, The Great Instauration, Aphorism 129, ‟Let the human race recover the right over nature which belongs to it by divine bequest and let power be given it; the exercise thereof will be governed by sound reason and true religion.” See also Farrington, Bacon, p. 22. See ‟The Masculine Birth of Time, or The Great Instauration [Restoration] of the Dominion of Man over the Universe: To God the Father.” ‟My only earthly wish, namely to stretch the deplorably narrow limits of man´s dominion over the universe to their promised bounds” (Farrington, Bacon, p. 62). ‟My dear, dear boy, what I purpose is to unite you with things themselves in a chaste, holy, and legal wedlock; and from this association you will secure an increase beyond all the hopes and prayers of ordinary marriages, to wit, a blessed race of Heroes or Supermen who will overcome the immeasurable helplessness and poverty of the human race” (Farrington, Bacon, p. 72).

[4] Sartor, p. 84. ‟That progress of Science, which is to destroy Wonder, and in its stead substitute Mensuration and Numeration, finds small favour with Teufelsdröckh, much as he otherwise venerates these two latter processes.

‘Shall your Science,’ exclaims he, ‘proceed in the small chink-lighted, or even oil-lighted, underground workshop of Logic alone; and man’s mind become an Arithmetical Mill, whereof Memory is the Hopper, and mere Tables of Sines and Tangents, Codification, and Treatises of what you call Political Economy, are the Meal?” (Sartor, p. 84).

‘The man who cannot wonder, who does not habitually wonder (and worship), were he President of innumerable Royal Societies, and carried the whole Mécanique Céleste and Hegel’s Philosophy, and the epitome of all Laboratories and Observatories with their results, in his single head, is but a Pair of Spectacles behind which there is no Eye. Let those who have Eyes look through him, then he may be useful.

‘Thou wilt have no Mystery and Mysticism; wilt walk through thy world by the sunshine of what thou callest Truth, or even by the Hand-lamp of what I call Attorney-Logic; and “explain” all, “account” for all, or believe nothing of it?” (Sartor, p. 86). Note Carlyle´s reference to Bacon´s ‟attorney-logic.”

[5] ‟Someday someone will write a pathology of experimental physics and bring to light all those swindles which subvert our reason, beguile our judgment and, what is worse, stand in the way of any practical progress. The phenomena must be freed once and for all from their grim torture chamber of empiricism, mechanism, and dogmatism; they must be brought before the jury of man´s common sense” (Goethe, The swindles of physics).

‟The mathematician refines his language of formula so highly; as far as possible he wants to incorporate the incalculable world into the realm of measure and number. Everything will then seem graspable, comprehensible, and mechanical, and he may be accused of an underlying atheism, for supposedly he has included the most incalculable element of all (which we call God), and thus has eliminated its special, overriding presence” (Goethe, Math turns the incalculable into . . . ).

‟A living thing cannot be measured by something external to itself; if it must be measured, it must provide its own gauge. This gauge, however, is highly spiritual, and cannot be found through the senses. The things we call the parts in every living being are so inseparable from the whole that they may be understood only in and with the whole” (Goethe, A living thing can´t be measured).

[6] ‟The battle with Newton is actually being conducted at a very low level. It is directed against a phenomenon which was poorly observed, poorly developed, poorly applied, and poorly explained in theory. He stands accused of sloppiness in his earlier experiments, prejudice in his later ones, haste in forming theories, obstinacy in defending them, and generally of a half-unconscious, half-conscious dishonesty” (Goethe, Battle with Newton).

[7] Egypt: Nun, Ra, ma´at, isfet, the opposite of ma´at, Apep (Apophis). Mesopotamia: Apsu, Tiamat, Marduk. Vedic India: Indra, Vritra. Zoroastrian Persia: Ahura Mazda, Ahriman. Canaanite: Baal, Yam, Mot. Hebrew: Yahweh, Leviathan, Rahab, Sheol. To which could be added a variety of New World agrarian deities (see Tedlock, Popol Vuh).

[8] See Martin, ‟In the Spirit of the Earth: Rethinking History and Time.” See Carlyle: ‟But deepest of all illusory Appearances, for hiding Wonder, as for many other ends, are your two grand fundamental world-enveloping Appearances, SPACE and TIME. These, as spun and woven for us from before Birth itself, to clothe our celestial ME for dwelling here, and yet to blind it–lie all-embracing, as the universal canvass, or warp and woof, whereby all minor Illusions, in this Phantasm Existence, weave and paint themselves. In vain, while here on Earth, shall you endeavour to strip them off; you can, at best, but rend them asunder for moments, and look through.”

[9] See Tedlock, Popol Vuh, pp. 145-148. Note that the Quiche Mayan creation story is obviously heavily influenced by the biblical Genesis story.

[10] Plato, Cratylus

[11] Farrington, p. 72. Elsewhere Bacon bashes the philosophy of the ancients for not having ‟yielded one achievement tending to enrich and relieve man´s estate” (Farrington, Bacon, page 125) and calls for ‟wholesome and useful inventions to war against our human necessities and, so far as may be, to bring relief therefrom” (Farrington, Bacon pp. 130-131).

Nietzsche expands much ink destroying God and Christianity, singling out St. Paul as a power mongering scoundrel. Curiously, he leaves Jesus unscathed. Nietzsche actually admired him. Be that as it may, Nietzsche denounces the Christian agenda of cleansing mankind of so-called sin as a ‟holy pretext … a ruse for draining life of its energy and of its blood” (Nietzsche, Why I Am a Fatality, p. 259).

[12] ‟terraqueous globe”: Carlyle, Sartor, p. 266.

[13] Carlyle, Sartor, p. 300. It is noteworthy that the so-called science of so-called Climate Change is nothing more than

[14] See Farrington, Bacon, page 20, 63-64, 84, 103, 106-107, 109, 110-113, 115, 118, 124, 130.

[15] See Nietzsche, The Antichrist, pp. 132-133, 139, 158-159. See Akenson, Saint Saul.

[16] Plato, Cratylus

[17] Rasmussen, Netsilik Eskimos, 208.

[18] Rasmussen, Netsilik Eskimos, 208.

[19] Basso, Wisdom, 121–22.

[20] Basso, Wisdom, 122, 127. “Once in his life a man ought to concentrate his mind upon the remembered earth,” mused the Kiowa poet N. Scott Momaday. “He ought to give himself up to a particular landscape in his experience, to look at it from as many angles as he can, to wonder about it, to dwell upon it. He ought to imagine that he touches it with his hands at every season and listens to the sounds that are made upon it. He ought to imagine the creatures there and all the faintest motions of the wind. He ought to recollect the glare of noon and all the colors of the dawn and dusk.” N. Scott Momaday, The Way to Rainy Mountain (Albuquerque NM: University of New Mexico Press, 1969), 83.

[21] Basso, Wisdom, 38, 88, 86, 46.

[22] Basso, Wisdom, 59.

[23] Basso, Wisdom, 128.

[24] Basso, Wisdom, 38.

[25] Basso, Wisdom, 39.

[26] Megan Biesele, Women Like Meat: The Folklore and Foraging Ideology of the Kalahari Ju/’hoan (Bloomington IN: Indiana University Press, 1993), 149.

[27] Biesele, Women Like Meat, p. 149.

[28] Biesele, Women Like Meat, p. 149.

[29] Bleek and Lloyd, Specimens, XV.

[30] Genesis 2:19 (KJV).

[31] Gerald Bruns, Modern Poetry, 190. “The concern of this book,” writes Bruns, “is with two extremes of speech—the speech of language and the speech of the world.” The “speech of the world” is “the language of Orpheus,” where language is numinous and creative. In the Orphic tradition, “the world is brought into being and upheld there by the energy of words.”

Bruns considers poetry a special language, as I do, which is why I have built these lectures with it. Poetry, alone, breaks the death spell that language has cast upon modern man and woman. “It is by means of poetry that the world finds itself present before man,” writes Bruns, drawing on Heidegger. “Indeed, the world is by this means able to speak to man, and this speech of the world, its appearance before man by means of words, is the Orphic poem.” A little further on, “our concern will be with the word conceived not as an object but as a presence, in the creation of which the poet is able to restore that primitive identity of word and world that the classical tradition of linguistic thought had brought progressively under attack” (2–4, 101, 206–7), emphasis mine.

I salute Bruns for this masterpiece, which has informed and stimulated my own thinking.

[32] Epic of Gilgamesh, 10.

[33] Rilke, Uncollected Poems: Rainer Maria Rilke, trans. Snow (New York: North Point, 1996), 159.

[34] The phrase “deep and magical,” as indicated above, is from Rilke, “Singer Sings before Child of Princes,” 169.

[35] “The first act whereby Adam constituted his rule over the animals was that he gave them names; that is, he annihilated them as beings.” (Die erste Akt, wodurch Adam seine Herrschaft über die Tiere konstitutiert hat, ist, dass er ihnen Namen gab, d.h. sie als Seiende vernichtete.) Hegel, Jenenser Realphilosophie, 211.

[36] Eiseley, “The Invisible Island,” in Unexpected Universe, 165.

[37] Rainer Maria Rilke, “The Panther,” in News of the Universe, 246. I prefer Bly’s translation to Edward Snow’s in New Poems, 1907, 73. I give these references for Rilke’s “Panther” because they are the two best translations, in my estimation. Hughes’s two poems, on the other hand, are readily available and are not filtered through a translator; hence I have not given a source.

[38] Coetzee, Lives of Animals, 51.

[39] Stevens, “A Primitive Like an Orb,” in Collected Poems, 465.

[40] By parenthetically inserting their real identities after their artificial English names, I am beginning to insist we come to terms with Paul John and Charlie Kilangak as Yup’iks. That is, as real people living in superposition in this place—real people who, by virtue of the sovereign physics of superposition, are this place. As these lectures unfold, their real persona, kangilngaq and qilangaq, will shift from a parenthetical, ethnographic dead-end to front and center in the text. For those unfamiliar with the term superposition, it will be explained in the next several pages.

[41] Stevens, “A Primitive Like an Orb,” 467.

[42] Stevens, “Ordinary Evening in New Haven,” 133–34.

[43] Rasmussen, Netsilik Eskimos, 307–14.

[44] Rasmussen, Netsilik Eskimos, 13–14. He adds, “Nevertheless, Orpingalik’s magic words were easier to understand than they usually are” (14).

[45] Rasmussen, Netsilik Eskimos, 13.

[46] Stevens, “Ordinary Evening in New Haven,” 134.

[47] Martin Heidegger, “The Origin of the Work of Art,” in Basic Writings, ed. David Farrell Krell (San Francisco: HarperCollins, 1993), 198, emphasis his.

[48] David Z. Albert, Quantum Mechanics and Experience (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1992), 7–15, 38.

[49] Wheeler, “Bohr, Einstein, and the Quantum,” 19–20.

[50] Wheeler, “Bohr, Einstein, and the Quantum,” 20.

[51] See Albert, Quantum Mechanics and Experience, 73-79.

[52] Note that tuntuvak is a variation of tuntu, which means “caribou,” according to the Alaska Native Language Center’s Yup’ik Eskimo Dictionary. Both words were almost certainly at one time phrases, acknowledging some kind of relationship between these two beings. See the Yup’ik Eskimo Dictionary, comp. Steven A. Jacobson, 2nd ed., 2 vols. (Fairbanks, AK: Alaska Native Language Center, University of Alaska, 2012), 1:646.

[53] Yup’ik Eskimo Dictionary (2012), 1:326.

[54] Yup’ik Eskimo Dictionary (2012), 1:567.

[55] Rilke, Uncollected Poems, 49.

[56] Biesele, Women Like Meat, 148.

[57] Wheeler, “Bohr, Einstein, and the Quantum,” 29.

[58] Rilke, “Gong,” in Uncollected Poems, 231.

[59] Eiseley, “The Cosmic Prison,” in Invisible Pyramid, 31.

[60] Biesele, Women Like Meat, 24.

[61] Frank G. Speck, Naskapi: The Savage Hunters of the Labrador Peninsula (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1935), 247–50, 96–97.

[62] Yup’ik Eskimo Dictionary, comp. Steven A. Jacobson (Fairbanks, AK: Alaska Native Language Center, University of Alaska, 1984), 630.

[63] Edward Adams, “Notes on the Birds of Michalaski, Norton Sound,” in The Ibis: A Quarterly Journal of Ornithology, ed. Osbert Salvin and Philip Lutley Sclater, 4th series, vol. 2 (London 1878), 420-21.

[64] Adams, “Notes on the Birds of Michalaski,” 422-42. The above list is just a sampling of the numerous Eskimo phrases (names) collected by Adams.

[65] Yup’ik Eskimo Dictionary (2012), 1:20.

[66] Stevens, “The Man with the Blue Guitar,” in Collected Poems, 194.

[67] Biesele, Women Like Meat.

[68] Walt Whitman, “Leaves of Grass, 1891–2,” in Complete Poetry and Collected Prose (New York: The Library of America, 1982), p. 231.

[69] Oliver, “Pink Moon—The Pond,” in Twelve Moons, 8.

[70] Claude Lévi-Strauss, Totemism, trans. Rodney Needham (Boston: Beacon Press, 1963), 101–4.

In the chapter “Totemism from Within,” Lévi-Strauss credits Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Discours sur l’origine et les fondements de l’inégalité parmi les hommes (London, 1776) with positing “an extraordinarily modern view of the passage from nature to culture” in early band and tribal societies, a view “based . . . on the emergence of a logic . . . of binary oppositions,” where man distinguished “himself” from “them” (animals), “coinciding with the first manifestations of symbolism” (101). Symbolism presumably in art, as in cave paintings, and symbolism in language: the symbolism of metaphor.

Building on Rousseau, Lévi-Strauss declares that mankind’s “original identification with all other creatures . . . as sentient beings . . . both governs and precedes the consciousness of oppositions . . . between ‘human’ and ‘non-human’ ” (101–2). Thus, with a nod to Rousseau’s ethnological speculations, Lévi-Strauss takes us back to Descartes and the subject-object dichotomy. Res cogitans and res extensa. “For Rousseau,” he elaborates, “this [dichotomy between human and non-human] is the very development of language, the origin of which lies not in needs but in emotions,” leading Lévi-Strauss to grandly conclude: “So that the first language must have been figurative” (102). He bolsters his claim with a passage from Rousseau’s 1783 “Essay on the Origin of Languages”: “As emotions were the first motives which induced men to speak, his first utterances were tropes. Figurative language was the first to be born, proper meanings were the last to be found. Things were called by their true name only when they were seen in their true form. The first speech was all in poetry; reasoning was thought of only long afterwards” (102, emphasis mine). See Jean-Jacques Rousseau, “Essay on the Origin of Languages,” in On the Origin of Language, trans. John H. Moran and Alexander Gode (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1966), 12.

Commenting on the above passage, Lévi-Strauss adds: “All-enveloping terms, which confounded objects of perception and the emotions which they aroused in a kind of surreality, thus preceded analytical reduction in the strict sense” (Totemism, 102). This would include all-enveloping, surreal terms like “the little walker” preceding analytical reduction to “fox.” “Metaphor, the role of which in totemism we have repeatedly underlined,” he concludes, “is not a later embellishment of language, but is one of its fundamental modes. Placed by Rousseau on the same plane as opposition, it constitutes, on the same ground, a primary form of discursive thought” (102, emphasis mine).

Note the primacy of metaphor and subject-object thinking in Lévi-Strauss’s proposed—albeit erroneous—origin of language and totemism. I see language and, for that matter, totemism as originating within the primordially accessible implicate order described by David Bohm and others—as a force of physics; in other words, within a firmament of reality that neither Rousseau, Lévi-Strauss, nor I can readily, if at all, access.

[71] Biesele, Women Like Meat, 122, 123, 138

[72] Rasmussen, Netsilik Eskimos, 208.

[73] Andrea Moro, I Speak, Therefore I Am: Seventeen Thoughts about Language (New York: Columbia University Press, 2016), 4.

[74] Biesele, Women Like Meat, 116, 138.

[75] Biesele, Women Like Meat, 88.

[76] Biesele, Women Like Meat, 116-121.

[77] Biesele, Women Like Meat, 74, 94.

[78] Jung, Memories, 273.

[79] Biesele, Women Like Meat,” 117.

[80] Hegel, Jenenser Realphilosophie, 211.

[81] Heidegger, “The Origin of the Work of Art,” 198, emphasis his.

[82] Biesele, Women Like Meat,” 116.

[83] Biesele, Women Like Meat,” 122, 123.

[84] Biesele, Women Like Meat, 116, 138.

[85] Genesis 2:19 (KJV)

[86] Descartes, Discourse, 36.

[87] Moro, I Speak, Therefore I Am, 4.

[88] Milton, Paradise Lost, ed. Barbara K. Lewalski (Oxford UK: Blackwell Publishing, 2007), 288 (lines 83-108).

[89] Eiseley, “The Long Loneliness,” in Star Thrower, 43–44.

[90] Stevens, “Esthétique du Mal,” in Collected Poems, 337, emphasis mine.

[91] Stevens, “A Thought Revolved,” in Collected Poems, 196.