"Naming":

The

Black Hole

of Consciousness

Calvin Luther Martin, PhD

October 23, 2024

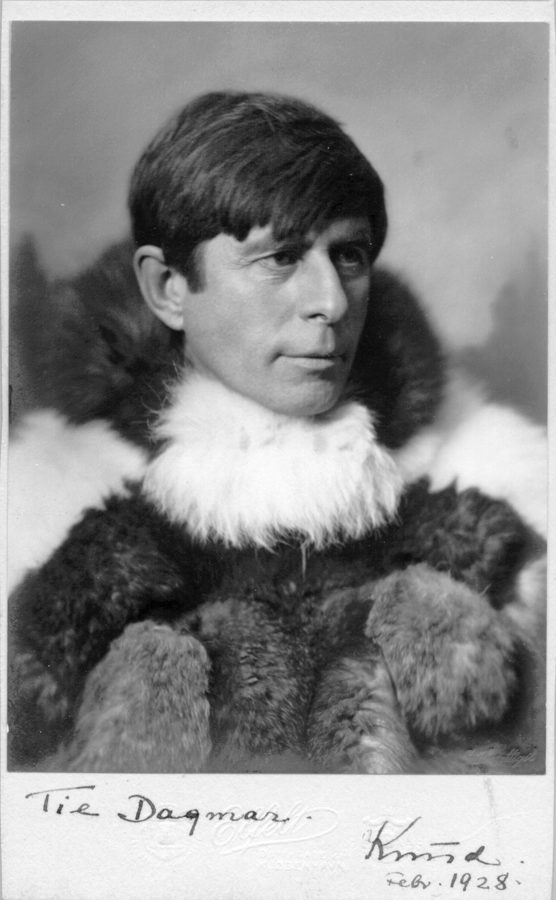

Knud Rasmussen, whose mother was Inuit

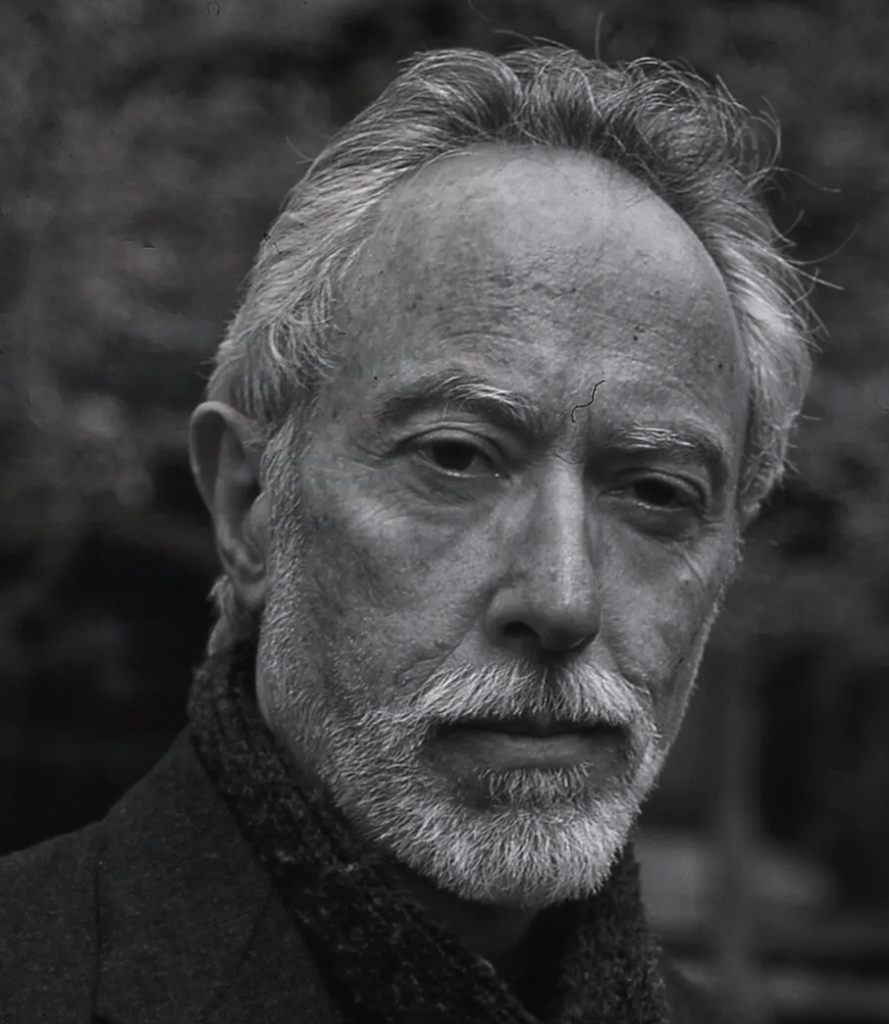

John Coetzee, Nobel laureate in literature

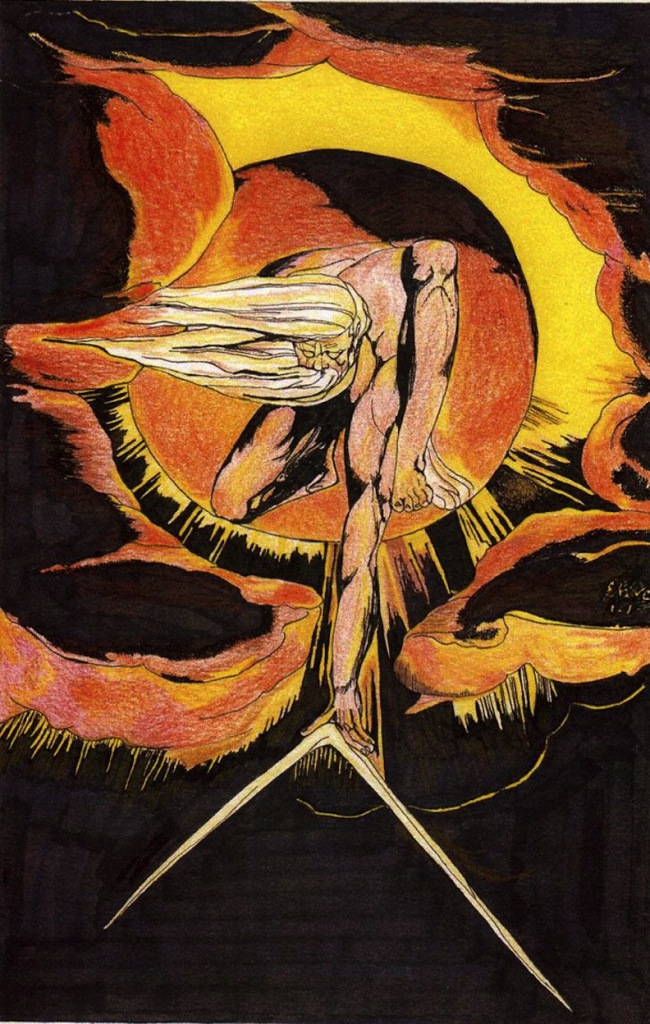

“Only let the human race recover the right over Nature which belongs to it by divine bequest.” (Image is Wm. Blake’s “Ancient of Days”)

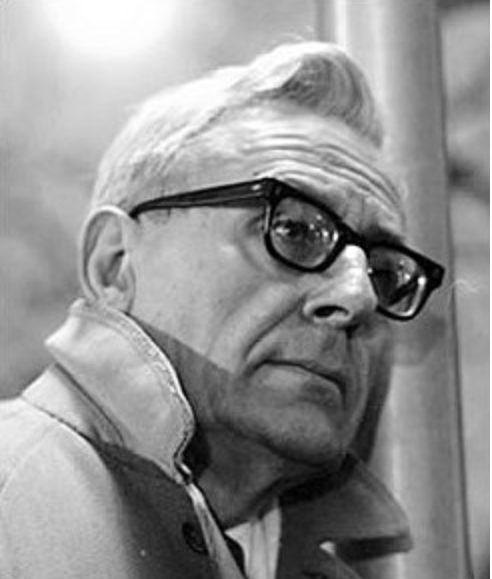

Loren Eiseley, Benjamin Franklin Prof. of Anthro., Univ. of Pennsylvania

W. H. Auden

Rainer Maria Rilke

Ludwig Wittgenstein

Plastic chairs. Fluorescent lights. Linoleum floor. The meeting is being held in what looks like a classroom. Alaska state biologist Randy Kacyon is up front, explaining that the state and feds are concerned about the diminishing moose resource up toward the Kilbuck range. It’s October 1994. Bethel, Alaska. I’m sitting in on the biannual meeting of the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta Subsistence Regional Advisory Council.

There are maybe a dozen men in the room, most of them in green shirts—fish and game personnel. They look official. The rest, dressed in faded flannel shirts and jeans, arms folded across the chest, look inscrutable and frankly out of place. As if they know they are party to a charade. They look like they belong in the pages of a National Geographic article. They are Yup’ik Eskimos.[1] Four of them—Harry Wilde, Paul John, Steven White, Antone Anvil—are members of the council, appointed by the US Secretary of the Interior. Their role is spelled out in one of the handouts:

The objective of the Council is to provide an administrative structure that enables rural residents who have personal knowledge of local conditions and requirements to have a meaningful role in the management of fish and wildlife and of subsistence uses of those resources on public lands in the region.[2]

Kacyon has just explained an elaborate plan, illustrated by charts and graphs, whereby state and federal wildlife managers propose to regulate the annual moose hunt to restore the population to sustainable levels. The men in the flannel shirts have been listening intently. Kacyon invites their comments.

I lean forward, every neuron in my brain on high alert. Kacyon has been speaking English; he neither speaks nor understands Yup’ik. Neither do I. Thankfully, there is a native interpreter, Sophie Evan. Like all Yup’iks, Evan speaks quietly. (Yup’ik is notably glottal and guttural, as if one is choking on one’s tongue. Imagine seal, walrus, and caribou vocalizations mixed together into a mucilaginous mishmash: seaweed with syntax.)

Paul John, Yup’ik elder from Toksook Bay, stirs as if awaking from reverie. His hand floats up into the air. This man lives fifty thousand years deep into time. He refuses to speak English because it’s the wrong language for this sentient place and its animal beings. After this meeting he will likely go out and buy bootlegged vodka and get drunk to deaden the pain and the memories. This man easily shape-shifts into seal, moose, caribou, or walrus when he dances to the singing and the drums. This man calls himself a Real Human Being, rooted within the mind and spirit and soul of this place. His name as a Real Human Being—his Yup’ik name—is Kangrilnguq.[3] This man is about to participate in the “decision-making process affecting the taking of fish and wildlife on the public lands within the region for subsistence uses.”[4]

Listen carefully. You are about to make contact with a consciousness that is nearly extinct. Let me rephrase this: you are about to experience the oldest language known to mankind. “We should be talking about this quietly,” Paul John warns softly, yet earnestly, “since, as we all know, tuntuvak [moose] hear us when we talk about them.” He pauses. “They might take offense at what we’re saying and not cooperate, or disappear altogether. We know this from experience.” (I took notes.)

He’s done. I count the seconds of silence. One. Two. Three. Up to ten or so. The biologist is grinning. He knows this is moonshine. More charitably, it’s anthropology. It’s not biology. He offers no response. Ten seconds tick by, and Randy Kacyon continues as if nothing—nothing at all—was said.[5]

This is what these lectures are about: contact with a language and consciousness that to Western ears is moonshine. It is the language of full presence. It is neither moonshine nor anthropology, nor is it dead. Polar explorer and anthropologist Knud Rasmussen witnessed its still-glowing embers among the Netsilik in the early 1920s, as did Frank Speck among subarctic Naskapi. Megan Biesele encountered it among Kalahari Bushmen in the 1970s. I have experienced it among the Navajo I lived with for the better part of a summer and during two years of living with Yup’ik Eskimos, Raven’s Children, by the Bering Sea.

I believe I know what was going through the biologist’s mind. It’s the dogma of all scientists schooled in the Aristotelian, Baconian, and Cartesian traditions reinforced by the biblical doctrine of human exceptionalism.[6] “We, the managers of the ecology . . . understand the greater dance, therefore we can decide how many trout may be fished or how many jaguar may be trapped before the stability of the dance is upset.”[7] (The words are Elizabeth Costello’s, the animal rights champion in J. M. Coetzee’s fictional Lives of Animals.) “The only organism over which we do not claim this power of life and death,” adds Costello sardonically, “is man. Why? Because man is different. Man understands the dance as the other dancers do not. Man is an intellectual being.”[8]

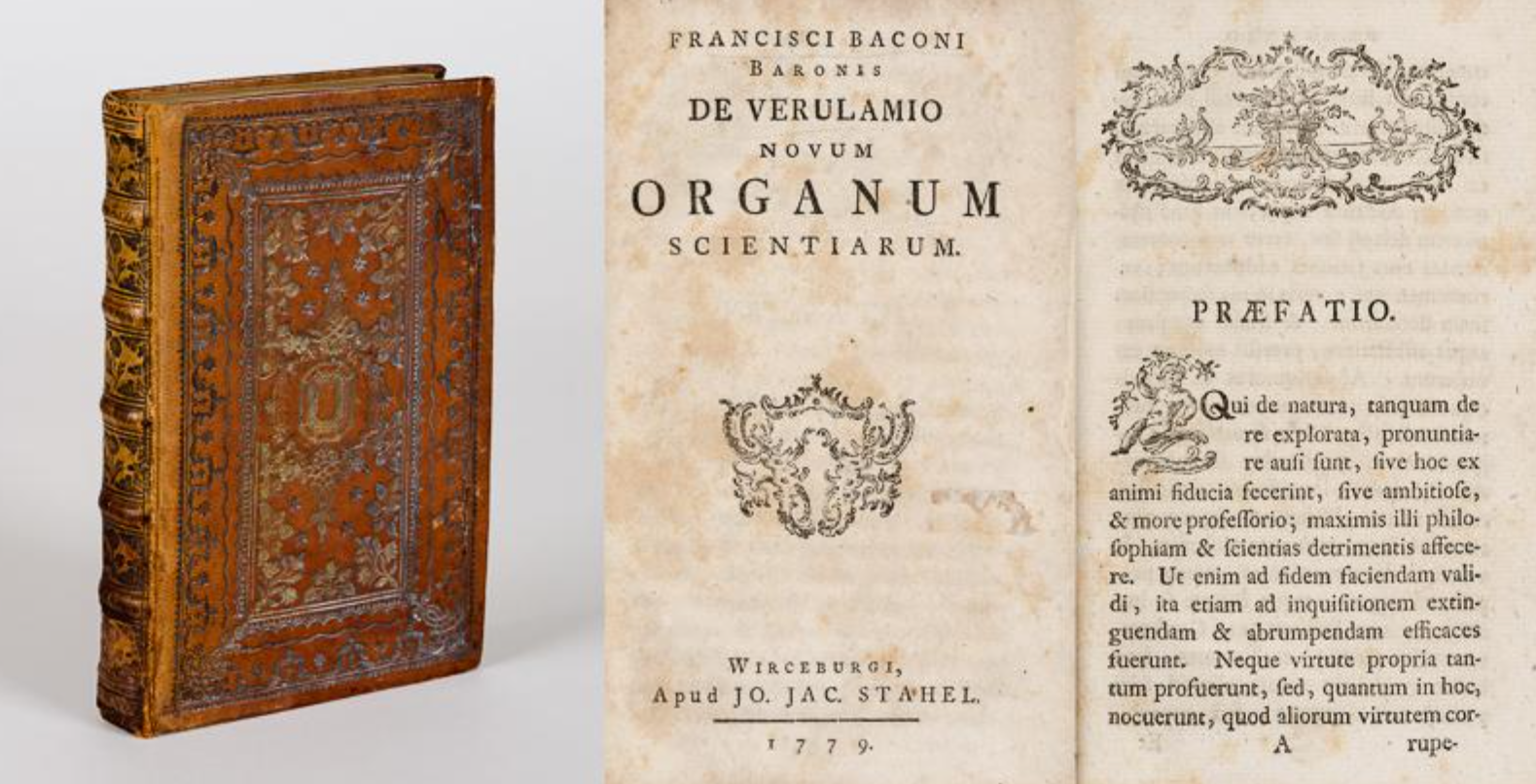

Costello, with her razor-edged charm, was trying to soften the blow. For the historical record can hardly be described as a dance, as Costello´s creator, John Coetzee, with a PhD in mathematics, knew well. The ‟managers of the ecology,” like the ones in the room in Bethel, understand the dance through inductive reasoning, an innocent-sounding proposition which turned into an epistemological and ontological trap indelibly written into the charter of science, thanks to the Elizabethan jurist Francis Bacon. In lines reminiscent of Jesus, Bacon declares, ‟I am come in very truth leading to you Nature with all her children, to bind her to your service and make her your slave.”[9] This is hardly the way one starts a dance with a partner, in this case Nature and all her children. Lest there be any doubt about Bacon´s intention as a dance partner: ‟Nature betrays her secrets more fully when in the grip and under the pressure of art than when in enjoyment of her natural liberty.”[10] ‟Only let the human race recover the right over Nature which belongs to it by divine bequest, and let power be given it; the exercise thereof will be governed by sound reason and true religion.”[11] That is, the sound, inductive reason of the scientific method.

A syllogism consists of propositions, a proposition of words, and words are the counters or symbols of notions or mental concepts. If then the notions themselves, which are the life of the words, are vague, ignorant, ill-defined (and this is true of the vast majority of notions concerning nature), down the whole edifice tumbles.

The syllogism being disposed of, what have we left? Induction. This is the one last refuge and support. On it are centred all hopes. This is the method which by slow and faithful toil gathers information from things and brings it to the understanding.[12]

‟Knowledge and human power are synonymous,” he continues, ‟since the ignorance of the cause frustrates the effect; for nature is only subdued by submission,” with the caveat that ‟Nature cannot be conquered but by obeying her.”[13] (Note Bacon´s use of the word ‟power.” We will revisit this ominous word in the writings of Friedrich Nietzsche.)

Albert Schweitzer called Bacon ‟´the man who drafts the program of the modern world view.´”[14] Fair enough, but it turns out there is a fatal flaw in Lord Bacon´s formula for the conduct of science, which, by the way, is as much theology as it is philosophy. Namely, Nature is to be conquered by obeying her. Conquered by obeying is an inherent contradiction, an oxymoron which these lectures will explore as we contemplate the nature of Nature and, by extension, the nature of reality.

Let us . . . in a spirit of responsibility concern ourselves with the task of promoting utility and greatness. Let us establish a chaste and lawful marriage between Mind and Nature, with the divine mercy as bride-woman. And let us pray God, the Father of man and nature as well as of lights and consolations, by Whose power and will these things are done, that from that marriage may issue, not monsters of the imagination, but a race of heroes to subdue and extinguish such monsters, that is to say, wholesome and useful inventions to war against our human necessities and, so far as may be, to bring relief therefrom. [15]

Thus saith the manifesto of modern science. Mankind, declared Bacon, by gift of the Almighty in the Book of Genesis, finally and decisively reclaiming ‟the power to conquer and subdue her [Nature], to shake her to her foundations.”[16] It is his Novum Organum, his Great Instauration. It is the ‟Masculine Birth of Time”: the manly, virile, courageous dawn of a new era. ‟My dear, dear boy, what I propose is to unite you with things themselves [Mother Nature] in a chaste, holy, and legal wedlock” —the blitzkrieg of science upon the earth. ‟And from this association you will secure an increase beyond all the hopes and prayers of ordinary marriages, to wit, a blessed race of Heroes or Supermen who will overcome the immeasurable helplessness and poverty of the human race, which cause it more destruction than all giants, monsters, or tyrants, and will make you peaceful, happy, prosperous, and secure.”[17]

Supermen who will overcome the helplessness and poverty of the human race. That would be scientists. Nietzsche´s Uber Mensch. ‟The kind of man,” explains Nietzsche, ‟who sees reality as it is; he is strong enough for this—he is not estranged or far removed from it, he is that reality himself, in his own nature can be found all the terrible and questionable character of reality: only thus can man have greatness.”[18] ‟´All Gods are dead: now we want the Superman to live´—let this be our last will one day at the great noontide! Thus spoke Zarathustra.”[19]

Bacon begat Nietzsche.[20] We will meet this prophesied Superman later on in these pages. The physicist.

But I get ahead of myself.

Bacon´s gospel is a catastrophe. It is a declaration of war against the earth and cosmos. This is not a dance, Ms. Costello. Let us call it for what it is. The Yup´iks at that phony meeting were well aware of this. Loren Eiseley wrestles, unsuccessfully in my view, with militant science in Francis Bacon and the Modern Dilemma.[21] Fortunately, there have been people like Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Thomas Carlyle, the poets Rainer Maria Rilke and Wallace Stevens, and Eiseley himself, who have denounced science-as-combat and endeavored to heal the wounds it has created and make mankind ‟less of an outlaw to himself, civilize him … back into that titanic otherness…from which he had arisen.”[22]

This is the mighty clash I witnessed that morning. Two profoundly different cosmologies smashing into one another.

‟We should be talking about this quietly, since, as we all know, tuntuvak hear us when we talk about them. They might take offense at what we’re saying and not cooperate, or disappear altogether. We know this from experience.” Kangrilnguq (Paul John), as spokesman for Raven´s Children, has countered the Interior Department´s Baconian belligerence with a demonstrative syllogism. Remember Bacon´s contempt for syllogisms: ‟A syllogism consists of propositions, a proposition of words; and words,” he continues, ‟are the counters or symbols of notions or mental concepts. If … the notions themselves, which are the life of the words, are vague, ignorant, ill-defined (and this is true of the vast majority of notions concerning Nature), down the whole edifice tumbles.”[23]

Words, when improperly referenced and devoid of reality, can bring down the whole house. He´s right. But, whose edifice and whose reality are we talking about? As I witnessed that day, words and symbols (mathematics) are unavoidable in any conversation about reality—and this is the point of these lectures. Except, we need to appreciate something right off: there was more going on in that room than a theoretical, semantic and cultural arm´s-length dispute about reality. For the Eskimo contingent, words are by definition a force of nature. For Paul John, Harry Wilde, Steven White, and Antone Anvil, language is physics. Randy Kacyon thought he was talking about moose—an object ‟out there.” Paul John responded with an epistemological and ontological bombshell, ‟No,” the man from Toksook Bay was saying, ‟this is impossible. There is no object `out there.´”

To give you a sense of what´s coming up in further lectures, consider Costello´s trout and jaguar, and Kacyon’s moose. For Raven´s Children, there is no “thing” (res extensa) existing outside us that is “trout,” “jaguar,” or “moose.” (Those of you familiar with Descartes will see that he´s going to be one of my targets later on in these lectures. Descartes is the philosophical high priest of res extensa.) Hence, the biologist’s moose made no sense to them. Same with bear, salmon, caribou. What exists, the old man was saying, is something perhaps best called presence—presence being the condition in which language and consciousness participate in what I will provisionally call Mind at Large.[24]

Plotinus likewise uses the word “presence” when talking about our awareness of this vast state of being—an awarness that “comes neither by knowing nor by the intellection that discovers the Intellectual Beings, but by a presence overpassing all knowledge. In knowing, soul or mind abandons its unity; it cannot remain a simplex. Knowing is taking account of things; that accounting is multiple. The mind thus plunging into number and multiplicity departs from unity” a

Let me simply say at this juncture that I am referring to the presence which farming man (’ādām, “the farmer”[25]) renounced and buried in his subconscious when, in an act of breathtaking betrayal, he named the animals and “annihilated them as beings,” observed Hegel.[26] Thus did ’ādām ominously collapse the conversation of grace (the gift) between man and his animal kinsmen, transferring it to a conversation on good and evil (to be explored further on with Nietzsche), cosmos and chaos (see Mircea Eliade), between man and his sky gods—the last nothing more than narcissistic human projections, about which W. H. Auden had this to say.

Since Adam, being free to choose,

Chose to imagine he was free

To choose his own necessity,

Lost in his freedom, Man pursues

The shadow of his images.

—W. H. Auden.[27]

Trout, jaguar, moose, bear, salmon, caribou: shadows of our imagination, their conscious presence erased. As I say, two dramatically different cosmologies in a head-on collision in that room in Bethel. A smash-up that began when the first Bible-toting Christian waded ashore in Terra Nova. Nor has it ended.

My goal is to flesh out this vaporous presence as much as possible in language. Immediately there is a problem: What to call this thing? Can it have a name?[28] How does one engage it with consciousness and speech? Sanskrit philosophy and Neoplatonism are helpful here. Poets strive to enter this realm. Rainer Maria Rilke, Wallace Stevens, Ted Hughes, Mary Oliver, and Randall Jarrell come to my mind. Doubtless poets around the world have for ages searched for this epiphany. Writing to his Polish translator, Rilke recounted such an experience. (Notice that he refers to himself in the third person.)

He remembered the hour in that other southern garden [Capri], when, both outside and within him, the cry of a bird was correspondingly present, did not, so to speak, break upon the barriers of his body, but gathered inner and outer together into one uninterrupted space, in which, mysteriously protected, only one single spot of purest, deepest consciousness remained. That time he had shut his eyes, so as not to be confused in so generous an experience by the contour of his body, and the infinite passed into him so intimately from every side, that he could believe he felt the light reposing of the already appearing stars within his breast.[29]

It turns out that physicists—some of them—likewise strive to come to terms with this realm. In physics it is called the quantum potential. David Bohm called it the holomovement or implicate order.[30]

My aim is to demonstrate that the convergent consciousness Rilke experienced and the theoretical physicist David Bohm tapped into is ancient and hardwired in us, and that it speaks a universal language. I witnessed this consciousness and language at the biannual meeting of the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta Subsistence Regional Advisory Council. I call it the language of wildness; the uncanny, participatory conversation of grace that is the birthright of all humanity.

I want it back. In fact, I am demanding it back from the arrogance and totalitarianism of humanism and, above all, science. “The limits of my language mean the limits of my world,” writes Wittgenstein in Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus.[31] (Logico derives from logos, Greek for word, speech, discourse, or reason. In Christian doctrine, borrowed from the Neoplatonic Word, Logos is Jesus. Logos as Word even turns up in Sanskrit philosophy/linguistics.[32]) I seek to smash those limits to restore the original and only legitimate and sane Logos, whose name is neither God nor Jesus nor Reason nor Brahman. If it had a name, it would be the Presence Where the Wild Things Are—where grace dwells.

Anticipating Wittgenstein by nearly a century, the German linguist Wilhelm von Humboldt famously observed that “man lives primarily with objects, indeed . . . exclusively, as language presents them to him. By the same act whereby he spins language out of himself, he spins himself into it, and every language draws about the people that possess it a circle whence it is possible to exit only by stepping over at once into the circle of another one.”[33]

Sanskrit philosophy takes von Humboldt´s observation even further. ‟Reality is understood only through speech (language) and it is understood only in the form in which it is presented by speech (word or language). But language cannot describe the intrinsic nature of things, although we know things only in the form in which words describe them.”[34] I will address the role of mathematics (as a symbol of logic) and physics (as applied logic) and their attempt to explain reality; both, however, being inherently crippled, Nietzsche pointed out, by ‟the lie of unity, the lie of matter, of substance and of permanence.”[35] Reason—what Carlyle, a mathematician by training, derided as ‟mensuration” and ‟numeration”[36]—‟is the cause of our falsifying the evidence of the senses. In so far as the senses show us a state of becoming, of transiency, and of change, they do not lie.”[37]

Such were the senses of Harry Wilde, Paul John, Steven White, Antone Anvil, whose fruitless message to the Department of the Interior invoked the oldest reality of all, accessed through the oldest language of all.

Join me as we step into this language.

________________

Footnotes

[1] Eskimo is a “colonial and derogatory word,” pointed out a former colleague to whom I showed this manuscript. I responded that in Alaska this is what they call themselves when dealing with kass’aqs (pronounced “guss-suck”; from Cossack, the word for the first whites they encountered in the nineteenth century).

While living with them, I referred to myself as a kass’aq, despite not being a Cossack, and they referred to themselves as Eskimos, despite not being whatever that word actually means, and regardless of whether or not it was derogatory. For the most part, they referred to themselves as Yup’ik or Yup’ik Eskimo. When speaking among themselves in Yup’ik, I believe they referred to themselves only as Yup’ik: “the real people of this place.”

Since they readily referred to themselves as Eskimos, I shall do so here.

[2] United States Dept. of the Interior Charter: Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta Subsistence Regional Advisory Council, 1994, 1.

[3] Even this name, Kangrilnguq, is not his real Yup’ik identity. His real identity was (he is now dead) kangilngaq, a phrase I explain in a later lecture.

[4] Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta Subsistence Council, 1.

[5] I recount this story in The Way of the Human Being (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1999). It forms the cornerstone of this lecture series, which is an elaboration on The Way of the Human Being.

[6] See G. Lloyd, ‟Aristotle on the natural sociability,” p. 277. For human exceptionalism, consider this from Bacon´s ‟Refutation of Philosophies”: ‟We are agreed, my sons, that you are men. That means, as I think, that you are not animals on their hind legs, but mortal gods. God, the creator of the universe and of you, gave you souls capable of understanding the world but not to be satisfied with it alone. He reserved for himself your faith, but gave the world over to your senses” (Bacon, Farrington, 106). I will take up Descartes in a later lecture.

[7] J. M. Coetzee, The Lives of Animals, ed. Amy Gutmann (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999), 54. Coetzee presented this story in the Tanner Lectures on Human Values at Princeton University, October 15–16, 1997.

[8] Coetzee, Lives of Animals, 54.

[9] Farrington 62

[10] Farrington 99

[11] Bacon, Great Instauration, Aphorism 129.

[12] Farrington, pp. 89, 115.

[13] Bacon, Aphorisms Book 1, #3; Farrington, p. 93.

[14] Farrington p. 29

[15] Farrington pp. 130-31

[16] Farrington p. 93

[17] Farrington p. 72

[18] Nietzsche, Why I Am a Fatality p. 257

[19] Nietzsche, Zarathustra, last page

[20] Bacon may well have been influenced by the apostate Dominican monk, Giordano Bruno, who in 1600 was burned at the stake by Pope Clement VIII for advocating Christian pantheism, among other heresies. Compare the following passage to Bacon´s ‟Great Instauration” (Great Restoration) of mankind´s dominion over Nature:

‟And he added that the gods had given intellect and hands to man and had made him similar to them, giving him power over the other animals. This consists in his being able not only to operate according to his nature and to what is usual, but also to operate outside the laws of that nature, in order that by forming or being able to form other natures, other paths, other categories, with his intelligence, by means of that liberty without which he would not have the above-mentioned similarity, he would succeed in preserving himself as god of the earth. That nature certainly when it becomes idle will be frustrative and vain, just as are useless the eye that does not see and the hand that does not grasp. And for this reason Providence has determined that he be occupied in action by means of his hands, and in contemplation by means of his intellect, so that he will not contemplate without action and will not act without contemplation.

‟In the Golden Age then, men were not because of Leisure more virtuous than beasts have hitherto been, but they were perhaps more stupid than many of the beasts. Now that difficulties have been born and needs have arisen among them, because of their emulation of divine acts and their adaptation to inspired affects, their minds have become sharpened, industries have been invented, skills have been discovered, and always, through necessity, from day to day new and marvelous inventions are summoned forth from the depths of the human intellect. Whence, always removing themselves more and more from their bestial being by means of their solicitous and urgent occupations, they more closely approach divine being.” Bruno, The Expulsion of the Triumphant Beast, 205–206.

[21] Give reference

[22] Eiseley, Star Thrower, pp. 237-38

[23] Farrington, ‟on the necessity of inductive reasoning”

[24] The term Mind at Large is from Aldous Huxley, The Doors of Perception and Heaven and Hell (New York: Harper & Row, 1954), 23–24.

[25] See Theodore Hiebert, The Yahwist’s Landscape: Nature and Religion in Early Israel (New York: Oxford University Press, 1966), 33–35, 38–40, 45–47, 59, 67–68, 70, 141. Note that ’ādām and hā’ādām both mean “farmer.”

[26] Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Jenenser Realphilosophie I: Die Vorlesungen von 1803–4, ed. Johannes Hoffmeister (Leipzig; F. Meiner, 1932), 211. See note 19, lecture x. Translation from Gerald Bruns, Modern Poetry and the Idea of Language: A Critical and Historical Study (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1974), 191.

[27] W. H. Auden, “For the Time Being: A Christmas Oratorio,” in Modern Poetry, ed. Maynard Mack, Leonard Dean, and William Frost, 2nd ed. (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1950), 222.

[28] See Kazantzakis, Greco, p. 152

[29] Rainer Maria Rilke, Duino Elegies, trans. J. B. Leishman and Stephen Spender (New York: Norton, 1939), 126.

[30] David Bohm, Wholeness and the Implicate Order (London: Routledge, 1980).

[31] Ludwig Wittgenstein, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1922), 149, statement 5.6, emphasis his.

[32] See Iyer, Complete p. 2

[33] Wilhelm von Humboldt, On Language: On the Diversity of Human Language Construction and Its Influence on the Mental Development of the Human Species, ed. Michael Losonsky (1836; reprint, New York: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 60.

[34] Pillai, Reality is understood . . .

[35] Nietzsche, Twilight, p. 18.

[36] Carlyle, Sartor p. 84

[37] Nietzsche, Twilight, p. 18

- Plotinus, The Enneads, trans. MacKenna, p. 617.[↩]