The

Island of Language

Part 2

Calvin Luther Martin, PhD

November 2, 2024

Wheeler’s colleagues erased the subject-object boundary

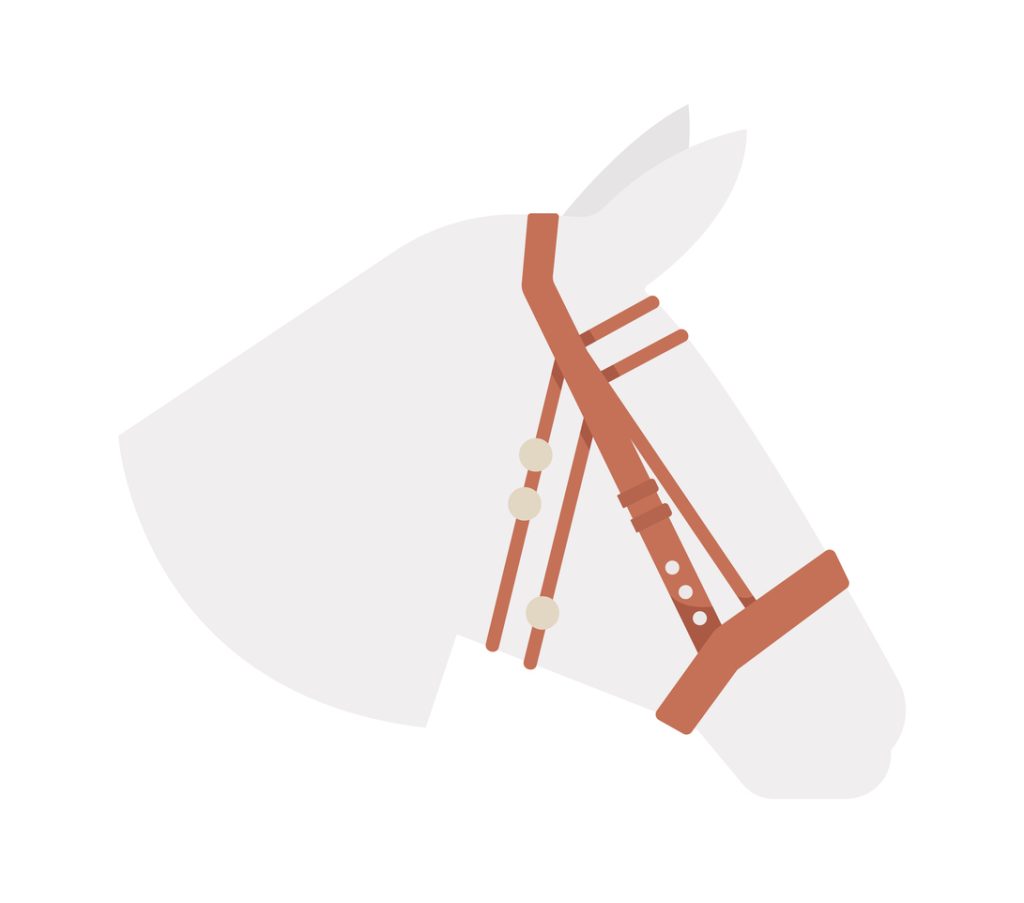

To name something is to control it—as in, put a bridle on it.

The wizard, Mr. Underhill

As long as the villagers “measure” this creature as “he-lives-under-a-hill,” the wave function of the gift remains intact and functioning.

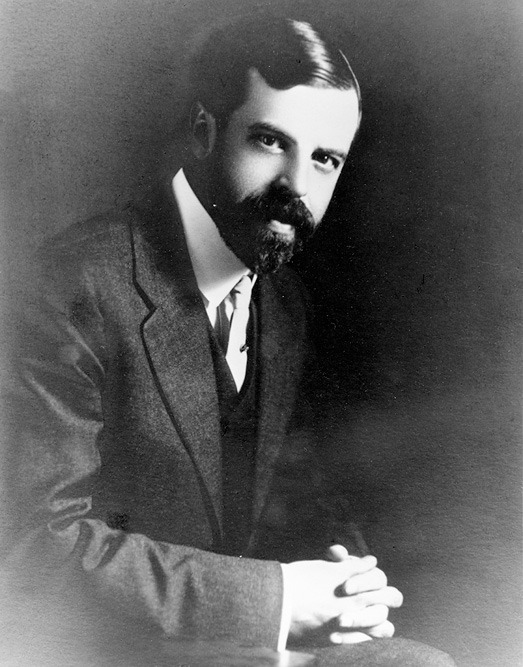

Prof. Alfred L. Kroeber

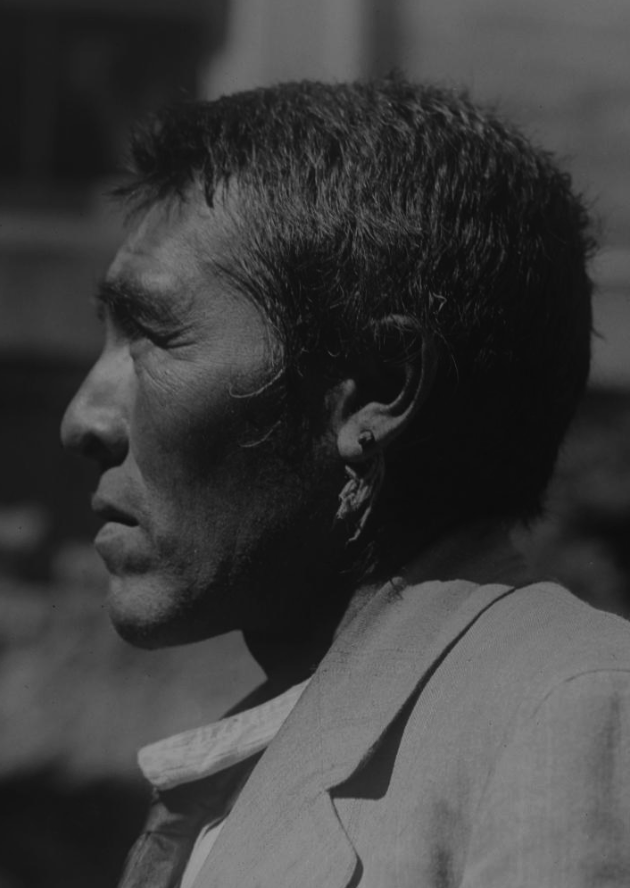

Ishi

For these people, Messieurs Rousseau and Lévi-Strauss, there is only the massive superposition of “l’endroit que je suis,” the place that I am. When this quantum state of limitless, undifferentiated awareness crashes, as it did for Ishi, there is nothing left.

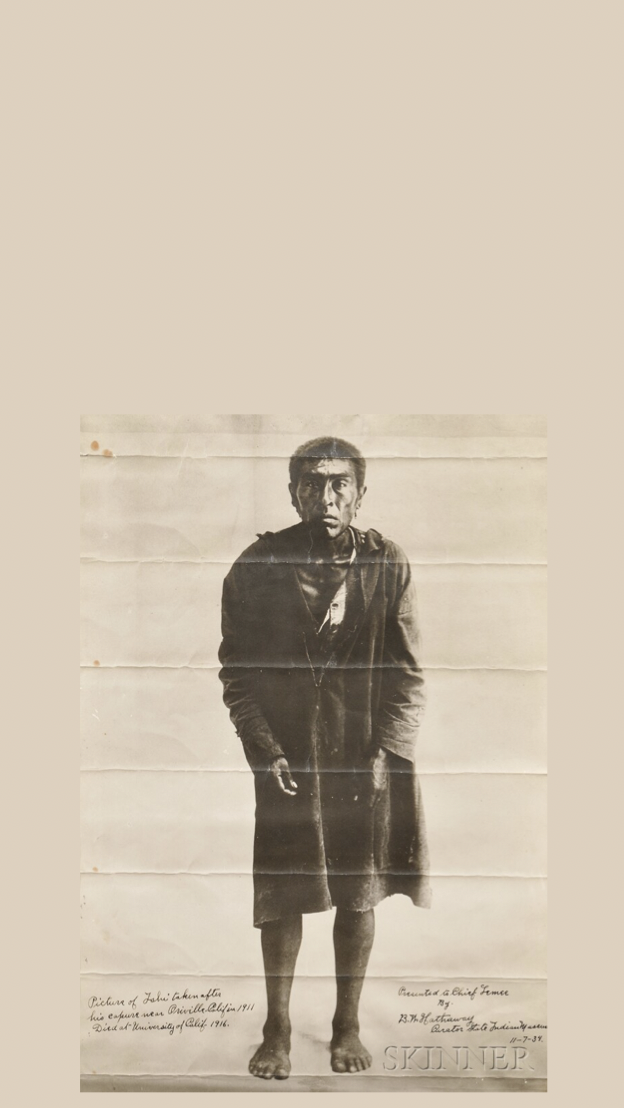

Photo taken of Ishi within hours of his surrendering to the cultural system that had collapsed the quantum reality of his “place that I am.”

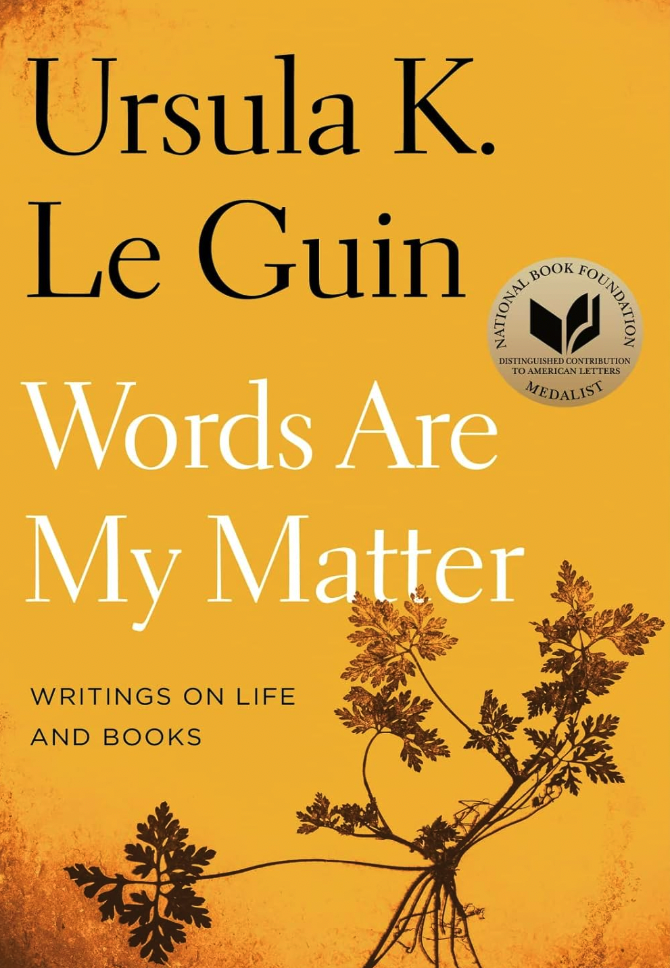

Ursula K. Le Guin,

who should have been awarded a Nobel Prize in liteerature

(I realize the handgun is anachronistic, but it makes the point.)

“The singers had to avert themselves / Or else avert the object.” (Avert, as when one looks slightly away from a planet or star in the night sky, the better to see it.)

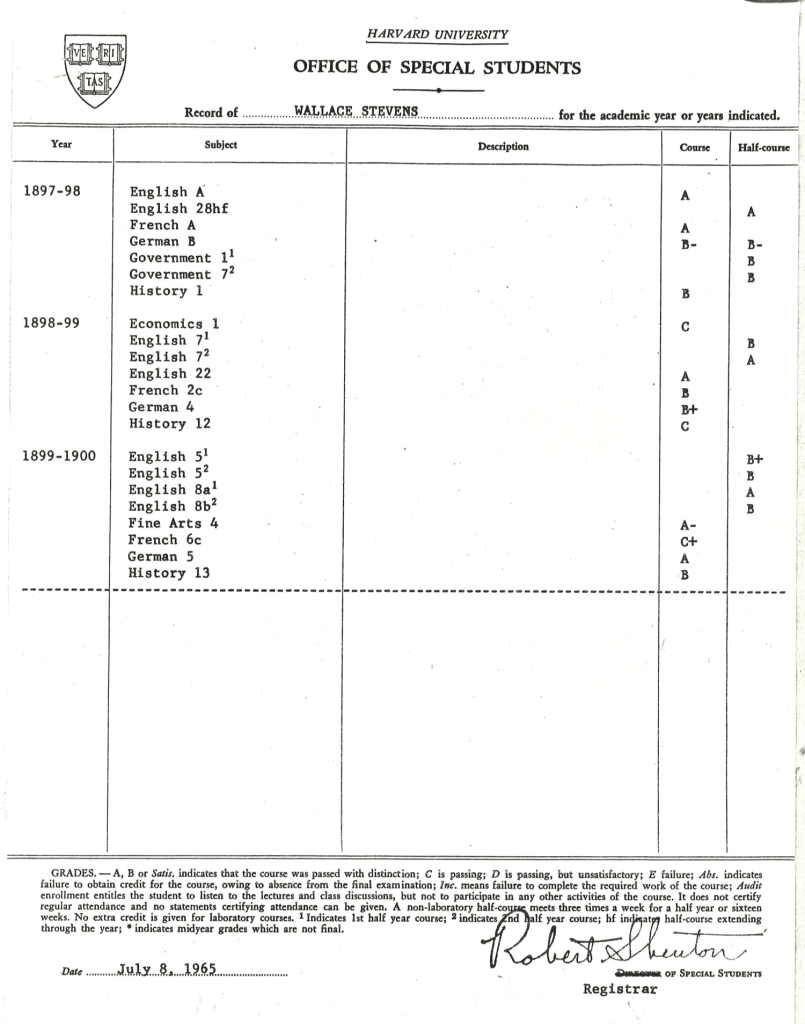

Wallace Stevens’s Harvard transcript. Click on the image, above, for a PDF of the Registrar’s entire file on young Mr. Stevens. Fascinating reading!

This pervasive structure—subject, verb, object—divides the totality of existence into separate entities (as in boxes or compartments), which are considered fixed and static in their nature.

Bohm went so far as to experiment with “new language forms in which a series of actions flow and merge into each other, without sharp separations or breaks.”

Nietzsche

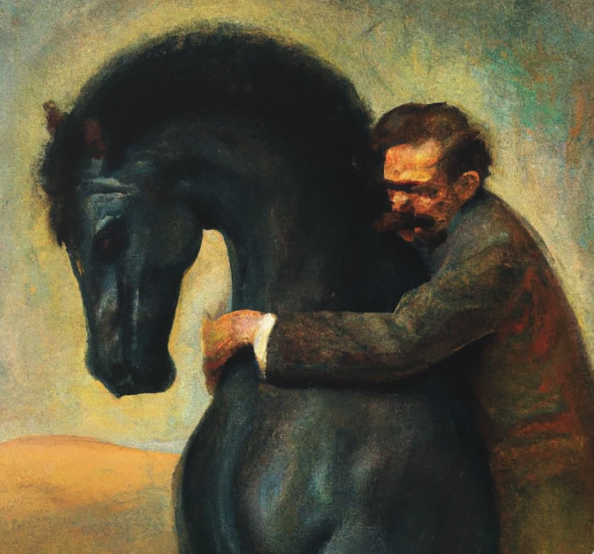

Nietzsche and the horse (Turin)

St. Paul’s breakdown on the road to Damascus (detail from painting by Caravaggio).

Prof. Franz Overbeck

T. S. Eliot

Nobel laureate in literature

“It is not that we can never separate objects from the observing process; we can once the interaction has ceased. But during the interaction the individual becomes an intrinsic part of the whole process and becomes transformed in the process.”

What if the “interaction”—a cloddish and unsatisfactory word—somehow never ceases between bee and flower?

There has been all sorts of speculation through the ages on the origins of language, from the utilitarian to the sublime.[37] My interest is in the use of language to grasp and manipulate, or contemplate, or deploy or harness the powers of the earth surrounding us, in particular the wild things. Thus, rephrasing my question above, how does pre- or nonagrarian Homo apprehend and engage the wild things essential for food and raiment or that are simply “good to think,” as Claude Lévi-Strauss famously put it.[38]

This is where naming takes center stage. As we have seen in the Hebrew Bible, the works of Beckett, Lévi-Strauss, Rousseau, Descartes, and the poets Rilke and Stevens and the host of native sources discussed earlier: to name or not to name is a vexing existential issue.

Recall the linguist Andrea Moro pronouncing, “One certainty is . . . striking: however much veiled in mystery, the ability to name things is, as far as we are concerned, the real big bang that pertains to us.”[39] I took issue with Moro. In the pages since, I have gone to considerable lengths to make the point that the true nature of reality is weird. It’s not Newtonian or even quantum mechanical; it’s spookier than either theory can explain. Bohm, Hiley, and Bell unveiled a universe where space-time is not primary and the subject-object boundary is illusory, a universe with an implicate order characterized by (a) nonseparation between the observing apparatus and what is observed or measured, (b) nonlocality in the spatial repercussions of observation or measurement, and (c) unavoidable mutual participation between the observer and what is being observed or measured. Newton’s universe and the quantum mechanical universe turn out to be special cases of a cosmic state of quantum potential.

In the truly real universe of quantum potential, naming things is indeed a big bang, though not for reasons the professor imagines. Witness the game of Twenty Questions described by John Archibald Wheeler. Wheeler entered the room believing that there was a specific word he had to guess by posing up to twenty questions to fellow players, who responded with either yes or no. He didn’t know they had changed the rules while he was outside. In fact, there was no word; the word would become manifest according to the questions Wheeler posed.

Wheeler’s companions changed the axis of reality from a Cartesian, Newtonian process (res cogitans, res extensa, which assume there is something “there” to be identified) to quantum potentiality, which transformed the unfolding of the word into a participatory process. The word came into being “only in relation to the process of manifestation.”[40] Wheeler’s colleagues erased the subject-object boundary; Wheeler (as subject) became entangled with his fellow players (as object).

Yes, I am saying there is a physics intrinsic to language, at the very least the naming powers of language applied to wild things. (Keep in mind that everything was perceived as wild by our Paleolithic ancestors.) Heidegger and Hegel both recognized this: to name something is to control it.

Loren Eiseley confronts this physics in “The Cosmic Prison”: “Language implies boundaries. A word spoken creates a dog, a rabbit, a man. It fixes their nature before our eyes; henceforth their shapes are, in a sense, our own creation.” One could say that the word that creates a dog or rabbit collapses the quantum potential into a classical physics state where these beings “are no longer part of the unnamed shifting architecture of the universe. They have been transfixed as if by sorcery, frozen into a concept, a word. Powerful though the spell of human language has proven itself to be, it has laid boundaries upon the cosmos.”[41] Boundaries that imprison us and the (no longer) wild things we name. “Because of speech, drawn from an infinitesimal spark along a nerve end,” mankind has managed “to lay a small immobilizing spell upon the nearer portions of his universe.”[42]

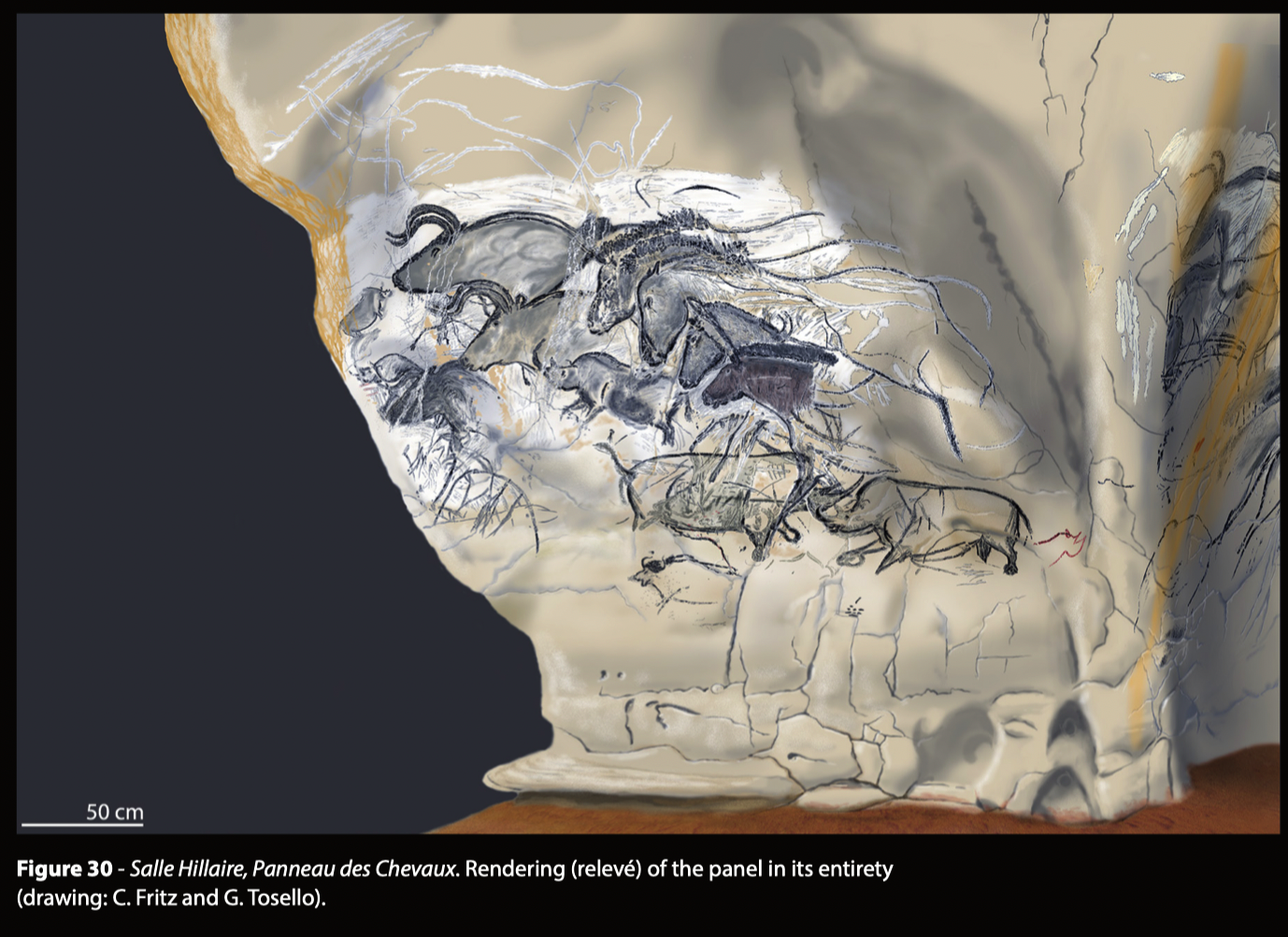

Part of the unnamed shifting architecture of the universe. Eiseley nails it! Now, immobilized.

The novelist Ursula K. Le Guin gives a thought-provoking illustration of the principle of control in her short story “The Rule of Names,” a tale of a far-off island in a world of wizards and magicians.[43] It’s worth pondering, for this is no ordinary writer, especially considering her parents, Alfred L. and Theodora Kroeber.

On this particular day the island’s wizard, as socially awkward as he is magically inept, has paused on his way home from grocery shopping to eavesdrop on a class being taught to a group of schoolchildren. The class is held outdoors in a sheep pasture—outdoors because the island has no classrooms. Palani, the young teacher, is “teaching an important item on the curriculum: the Rules of Names.” The wizard, Mr. Underhill, stops to listen and watch.

“Now you know the Rules of Names already, children. There are two, and they’re the same on every island in the world. What’s one of them?”

“It ain’t polite to ask anybody what his name is,” shouted a fat, quick boy, interrupted by a little girl shrieking, “You can’t never tell your own name to nobody my ma says!”

“Yes, Suba. Yes, Popi dear, don’t screech. That’s right. You never ask anybody his name. You never tell your own. Now think about that a minute and then tell me why we call our wizard Mr. Underhill.” She smiled across the curly heads and the woolly backs at Mr. Underhill, who beamed, and nervously clutched his sack of eggs.

“ ‘Cause he lives under a hill!” said half the children.

“But is it his truename?”

“No!” said the fat boy, echoed by little Popi shrieking, “No!”

“How do you know it’s not?”

“ ‘Cause he came here all alone and so there wasn’t anybody knew his truename so they couldn’t tell us, and he couldn’t—”

“Very good, Suba. Popi, don’t shout. That’s right. Even a wizard can’t tell his truename. When you children are through school and go through the Passage, you’ll leave your childnames behind and keep only your truenames, which you must never ask for and never give away. Why is that the rule?”

The children were silent. The sheep bleated gently. Mr. Underhill answered the question: “Because the name is the thing,” he said in his shy, soft, husky voice, “and the truename is the true thing. To speak the name is to control the thing. Am I right, Schoolmistress?”

She smiled and curtseyed, evidently a little embarrassed by his participation. And he trotted off towards his hill, clutching his eggs to his bosom. Somehow the minute spent watching Palani and the children had made him very hungry.[44]

No one knew the powerful wizard’s name. Hence, no one could control him. His relationship with the islanders is best characterized as a gift: the gift of his medicinal spells and awkward friendship, and their gift to him of homespun friendship and food.

Until the day a swashbuckling young wizard sails into the harbor and begins making indiscreet inquiries about Mr. Underhill’s background, about which no one knows anything. It turns out Underhill is a horrid dragon—who stole a treasure trove of jewels from the ancestors of the newly arrived wizard—masquerading as a bungling mage.

There is a showdown between the two, climaxing in the newcomer hurling Mr. Underhill’s truename at him, thinking thereby to force his foe into his true form. It works, but backfires, since Underhill’s true form, conforming to his truename, is the vicious dragon who stole the loot. The next instant, the horrified young wizard is reduced to a “reddish-blackish trampled spot, and a few talon-marks in the grass.”[45]

Now that he’s under the control of his truename, Yevaud the dragon begins preying on the villagers. With this the story ends.

Think of the name Mr. Underhill as the equivalent of “the little walker” in Rasmussen’s conversation with the Netsilik shaman, Orpingalik. Or “a rain’s thing” in Bushman epistemology. As long as “he-lives-under-a-hill” is able to exist in this undifferentiated state, this wild thing can have a gift relationship with the community: the gift of its medicinal skills and friendship, and their reciprocal gift of cracker-barrel companionship and food. In the language of the quantum potential, as long as the villagers “measure” this creature as “he-lives-under-a-hill,” the wave function of the gift remains intact and functioning.

Then comes disaster. The stranger instantly collapses the wave function of the gift when he confronts “he-lives-under-a-hill” with the “truename” Yevaud, the dragon. Against its will, wildness has been forced to manifest as a hideous dragon, with catastrophic results for everyone. The gift has given way to prediction and control; a transformation, in this instance, something like transforming natural uranium into an atom bomb.

Underhill can no longer function within the gift. I don’t want to call it the economy of the gift. It’s more fundamental than economics; it’s physics.

To call “The Rule of Names” fiction is as shallow as calling Monet’s paintings impressions of his gardens. Monet was getting at something outside space-time and the subject-object dichotomy, what the painter Fairfield Porter called “first timeness—the world starts in this picture.”[46] Le Guin accomplishes this with language, with a story about a mage without a name, who, as a result, can perform, exist, and communicate within the boundless, timeless gift.

She got her story from a childhood story, I believe, told by her parents. The story of a mysterious man without a name, a “wild man” who materialized out of California’s Mount Lassen wilderness in August 1911.

Here it is, in brief. Le Guin’s father, the Berkeley anthropologist Alfred L. Kroeber, sent his assistant T. T. Waterman on the train to fetch the Wild Man of Oroville, as locals called him, who was then ensconced in the Lowie Museum of Anthropology (today the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology) as a specimen of the Stone Age.[47]

Professor Kroeber had no idea what the man’s name was, and no way of finding out. “Reporters demanded to know his name, refusing to accept Kroeber’s word that the question was in the circumstances unmannerly and futile.” At this point a boorish acculturated Yana named Batwi “intervened, engaging to persuade the wild man to tell his name—a shocking gaucherie on Batwi’s part. The wild man, saving his brother Yana’s face, said that he had been alone so long that he had had no one to give him a name—a polite fiction, of course. A California Indian almost never speaks his own name, using it but rarely with those who already know it, and he would never give it in reply to a direct question.”[48] Which is exactly what Palani reminds the class in “The Rule of Names”: “There are two, and they’re the same on every island in the world. . . . You never ask anybody his name. You never tell your own.”

Le Guin’s father, aware of the rules, finessed the problem by settling on Ishi, the Yana word for “man.” “He never revealed his own, private, Yahi name,” recalls Le Guin’s mother, Theodora. “It was as though,” she muses, “it had been consumed in the funeral pyre of the last of his loved ones. He accepted the new name, answering to it unreluctantly. But once it was bestowed it took on enough of his true name’s mystic identification with himself, his soul, whatever inner essence of a man it is which a name shares, that he was never again heard to pronounce it.”[49]

Recall this line from Rousseau’s “Essay on the Origin of Languages”: “Things were called by their true name only when they were seen in their true form.”[50] I quoted it in my critique of Lévi-Strauss’s silly Rousseauvian theory on the origin of language.[51] My response to M. Rousseau and le grand professeur Lévi-Strauss: “Réveillez-vous, mes amis! Ce n’est pas vrai! Dans l’ordre implicite connu de vos sauvages, il n’y a pas de véritable forme. Par conséquent, il n’y a pas de véritable nom.” Wake up, my friends! This is not true! In the implicate order known to your savages, there is no true form. Hence, there is no true name.

Ishi, like all the aboriginal people I have invited to this seminar on language, knew this. For these people, Messieurs Rousseau and Lévi-Strauss, there is only the massive superposition of “l’endroit que je suis,” the place that I am. When this quantum state of limitless, undifferentiated awareness crashes, as it did for Ishi, there is nothing left.[52]

Ishi died several years after arriving in San Francisco and acquiring a name, an address, gainful employment as assistant janitor at the UC Berkeley Museum of Anthropology, and tuberculosis. Kroeber, deeply affected by this otherworldly man, was reluctant to speak of him after his death. It was Kroeber’s wife, Theodora, who wrote Ishi’s biography, a story of mystery, heartbreak, and tragedy that her daughter undoubtedly grew up with and saw mirrored, somehow, in her parents. A story she turned into one of her own.

We will come back to Ishi in the next chapter.

“The Rule of Names” and “The Word of Unbinding” (another short story by Le Guin) are explorations into a realm where words are controlling and performative[53]— as if alive, as they were for the Netsilik Eskimos Nâlungiaq and Orpingalik and for the Bushman /haṅǂkass’ō/. Note Le Guin’s boundary-smashing essays on therolinguistics, the “language of wild things,” as in this passage:

And with them, or after them, may there not come that even bolder adventurer—the first geolinguist, who, ignoring the delicate, transient lyrics of the lichen, will read beneath it the still less communicative, still more passive, wholly atemporal, cold, volcanic poetry of the rocks: each one a word spoken, how long ago, by the earth itself, in the immense solitude, the immenser community, of space.[54]

Le Guin was a language time traveler, traveling backward in “The Rule of Names” and “The Word of Unbinding” and forward in “The Author of the Acacia Seeds and Other Extracts from the Journal of the Association of Therolinguistics.”

I’m interested in her backward look—when language was performative and, most importantly, not fragmenting. David Bohm explains:

Wholeness is what is real, and . . . fragmentation is the response of this whole to man’s action, guided by illusory perception, which is shaped by fragmentary thought. In other words, it is just because reality is whole that man, with his fragmentary approach, will inevitably be answered with a correspondingly fragmentary response. . . . What is needed is for man to give attention to his habit of fragmentary thought, to be aware of it, and thus bring it to an end. Man’s approach to reality may then be whole, and so the response will be whole.[55]

Fragmentation is one of the chief reasons language is crippled. Notice the cascading process in “The Rule of Names” and, for that matter, “The Word of Unbinding.” We see it in Knud Rasmussen’s notes on Netsilik language, in Megan Biesele’s and Lucy Lloyd’s conversations with Bushmen, Keith Basso’s with the Apache, and my own with Yup’ik Eskimos. In each instance a seemingly vague word or phrase (e.g., pisuk·a·ciaq, “the little walker”) triggers the spooky physics Einstein referred to. David Bohm would say the phrase (e.g., pisuk·a·ciaq) sets up a wave function of nonlocal, participatory, nonfragmentary engagement with wholeness, that is, an engagement with the implicate order.

This engagement instantly collapses when the wholeness accessed by pisuk·a·ciaq is named fox. Pisuk·a·ciaq is ejected from wholeness into a fragmented state of being. The same happens when a rain’s thing is named and, as a result, stripped of its access to wholeness and fragmented into fungus. Same when too-oó-slik (see Edward Adams, above) is named common loon: it’s ejected from wholeness. Same, even, when he-who-lives-under-a-hill (wholeness) is forced to become Yevaud. You get the picture.

But there’s more. When we collapse the implicate order (superposition) by naming things as Adam is said to have done at Jehovah’s direction, we do more than eject these phenomena (e.g., pisuk·a·ciaq, rain’s thing, too-oó-slik) from wholeness; we eject ourselves, as well. This is the original sin. We engineered our fall out of wholeness —Professor Moro, take note—by naming things.

Think about this. It’s very strange. We have no awareness of this process in our modern use of language. That is, as adults we are oblivious to it in our speech. Little children are a different story; they seem to have an engagement with wholeness built into their earliest language. (Can language invoke a physics? Absolutely! We implicitly cast a spell of physics every time we speak.)

Wallace Stevens confronts this curious process in his “Credences of Summer.” What he’s grappling with is the physics of Descartes’s subject-object disconnection: the dichotomy that exists solely because modern man, through language, calls it into existence. Yes, it’s a choice, and yes, it’s a matter of physics.

Since the lurch into the Neolithic, mankind has assumed this is the only legitimate physics-of-language: res cogitans and res extensa. In western thought, we find it prevalent among the pre-Socratics and throughout the Bible, especially as Deus cogitor and Deus extensa. Descartes gave the ideology its most succinct analysis and justification at a perfect moment for inflicting maximum damage: when Europe needed a new and better physics-of-language to justify the usurpation of the New World.

Let me elaborate. Before the 16th century, biblical (that is, papal: sky god) and monarchical divine right (sky god) justifications for conquest had sufficed. The new mentality of science and secularism demanded something (a) more accessible than Aristotle’s ponderous teachings on abstract (“abstracted”) thinking and self-centered consciousness, and (b) more contemporary and credible than Old and New Testament imperialism derived from Deus cogitor, Deus extensa, or Christus cogitor, Christus extensa. Descartes to the rescue! Bypassing the Greeks and the Old and New Testament God, Descartes handed the second generation conquerors of the Americas (and later, South Pacific) the weaponized physics-of-language they required.

It was like handing them a loaded gun for hunting down and annihilating the implicate order. Ishi being the last survivor. I literally grew up among the burial mounds and spirits of an early 18th-century reservation (a kind of “Carlisle Indian School”) on the lower Ottawa River which was merely the mopping up—the final punctuation point—of the collapse of the implicate order through the horrifying engines of the fur trade (the subject of my first book), French brandy, missionary brainwashing and persecution, and above all appalling epidemic disease in a virgin soil population.

As a further aside, the watershed separating the Paleolithic from the Neolithic is not hunting-and-gathering versus farming and patoralism, or sky gods versus animism (or some other lame term like pantheism). For these are epiphenomena. The inflection point is a breathtaking shift in the physics-of-language and consciousness. The universe, including of course the earth and all that dwell therein, intrinsically operates by the physics described by Bohm et al. as the implicate order. So did Homo, once upon a time—Paleolithic Homo, that is. Neolithic man rejected the physics of the implicate order for a physics we imagined we could control, first through the surrogacy of fake, deputized sky gods, and, when the credibility of these celestial mannequins and their earthly vicars petered out (as Nietzsche famously observed in his “God is dead” remark), the soi-disant keepers of culture and managers of society, their thirst for power unquenched, switched allegiance to the Logos of science and a billowing narcissism they called humanism and, other times, reason. And this is why we are in the hopeless mess we’re in as I write this.[56] Hopeless in the aggregate. Not hopeless as individuals. The distinction is vital and huge.

Back to Wallace Stevens’s exposition on the implicate order. “Far in the woods,” he begins in “Credences of Summer,” “they sang their unreal songs, / Secure.” Immediately we know there’s something wrong. The singers are in a wild place (“far in the woods”) singing their beseeching yet unreal songs. It turns out they are singing something having to do with “summer in the common fields.” And yet, “deep in the woods,” “it was difficult to sing in face / Of the object,” which, as I say, is vague; again, something having to do with summer in the common fields.

Stevens is setting up a subject-object dilemma. The subject is the singers. The object—is not clear. “The singers had to avert themselves / Or else avert the object.” (Avert, as when one looks slightly away from a planet or star in the night sky, the better to see it.) I warn you: we are now entering Einstein’s spooky physics. Stevens is setting up a wave function of nonlocal, participatory, nonfragmentary engagement with wholeness—an engagement with the implicate order. Hang on tight! The next three lines are full-throttle, implicate order physics:

They sang desiring an object that was near,

In face of which desire no longer moved,

Nor made of itself that which it could not find . . .

Go ahead, read these three lines again, to truly grasp Stevens’s meaning. It’s worth puzzling over: it’s profound.

Wallace Stevens was a philosopher of the highest caliber—earning his living working as an attorney for an insurance company, which is a bit like Einstein working for the Swiss patent office, or Melville working as a New York City customs inspector. Note that in his years as an undergraduate at Harvard, one of Stevens’s closest friends was the philosopher George Santayana, famous for the quote, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” I have a copy of Stevens’s Harvard transcript (see the image to the left) and I find no evidence he took a course from Prof. Santayana. On the other hand, read Santayana’s 1900 essay, “Interpretations of Poetry and Religion,” and you understand in a flash why these two bonded.

The great function of poetry is precisely this: to repair . . . the material of experience, seizing hold of the reality of sensation and fancy beneath the surface of conventional ideas, and then out of that living but indefinite material to build new structures, richer, finer, fitter to the primary tendencies of our nature, truer to the ultimate possibilities of the soul. Our descent into the elements of our being is then justified by our subsequent freer ascent toward its goal (Santayana, p. 161).

You see why I rely heavily on poetry, especially Rilke and Stevens, both of whom fulfilled Santayana’s Great Commission of poetry.

But I digress. The root of the conundrum that Stevens and others struggle with lies in the Island of Language “bringing about the fragmentation of thought”; that is, fragmentation of the Globe of Thought. “The subject–verb–object structure of modern languages implies that all action arises in a separate subject,” continues Bohm, “and acts either on a separate object or else reflexively on itself. This pervasive structure . . . divides the totality of existence into separate entities, which are considered . . . fixed and static in their nature.”[57]

Hang onto the words “fixed” and “static”—as in “immobilized” or “frozen in time.” We will encounter them again with Socrates who, like Bohm, was troubled by what I call the “physics” of language—the physics of names and naming, in particular. Socrates called it a “battle of names”: those objects bearing a name “expressive of motion” (what he elsewhere calls “process,” “flux,” and “transition”) versus objects bearing a name “expressive of rest,” by which he meant the named object is always “in the same state.” a

Bohm went so far as to experiment with “new language forms in which . . . a series of actions . . . flow and merge into each other, without sharp separations or breaks.” He wasn’t trying to invent “a new language as such, but . . . a new mode of using the existing language . . . mainly to give insight into the fragmentary function of the common language.” He called this new mode the “flowing mode,” being essentially the quantum potential in linguistic form. “Thus, both in form and in content . . . language will be in harmony with the unbroken flowing movement of existence as a whole.”[58]

We don’t need new language forms. We need the old ones, like Dudley Patterson’s white-rocks-lie-above-in-a-compact-cluster, and the little walker, a rain’s thing, and the python-that-is-an-elephant, where there is not a whiff of prediction and control, no “small immobilizing spell” upon the “unnamed shifting architecture of the universe.”[59]

This leaves just one option for intercourse between humans and wild things: the gift. The mind not wired for praxis lives by the unfolding and enfolding of the gift, where the little walker, Paul John’s tuntuvak, a rain’s thing—even Le Guin’s “he lives under a hill”—“are not static concepts, but part of the underlying process.”[60] Only through the explicate order of the gift do we experience the implicate order of the universe.[61]

Consider Equus. Something intrinsic to Equus exploded Nietzsche’s famously analytical mind. This is more than a case of a man distraught over the mistreatment of a horse—a plausible explanation for almost anyone else, but unlikely for the man famous for smiting fellow philosophers hip and thigh with the jawbone of philology, the man who tore the mask off every orthodoxy he gazed upon, including belief in God and Satan, the man who brashly exclaimed, “The world seen from within, the world defined and designated according to its ‘intelligible character’ . . . would simply be [the] ‘Will to Power,’ and nothing else.”[62]

In a flash of identity, Nietzsche and Equus “locked in a mighty unity” that left the philosopher clinging to the neck of the manifestation before him.[63] The mental state of Nietzsche, who was already showing signs of eccentricity, some of it extreme enough to alarm his hosts, rapidly deteriorated in the days following the incident. (Following the horse encounter, when a “mental therapist” named Professor Dr. Turina was summoned to the house by his landlord, Nietzsche insisted he wasn’t deranged.[64]) One can only conjecture what Nietzsche perceived in this creature, what portal to another reality.

Compare Nietzsche’s experience to Saul’s famous breakdown on the road to Damascus, recounted in the Acts of the Apostles. Let’s include Thoreau’s crack-up on Katahdin and Jung’s flight from Africa in our analysis. Certainly there were significant differences in each episode and each individual’s mental state (Nietzsche was already going mad, it appears, almost certainly from neurosyphilis), but these differences should not obscure the fact that none of them had the intellectual equipment to process the implicate order that manifested itself in this terrible moment. Nietzsche, who insisted his readers get beyond good and evil, was granted his wish after a fashion, and couldn’t deal with the new reality given to him. (Again, it’s difficult to disentangle Nietzsche’s progressive dementia from whatever message was bestowed by Equus.) Saul’s paradigm of good and evil was likewise shattered in his moment of confrontation. (Unlike Nietzsche, Saul retooled himself in grace and became a saint.)

I sympathize with these men, all of them. I, too, had an encounter where I was—may I call it, deconstructed? Saul became blind for a brief period. Nietzsche became hopelessly unhinged. The element common to each of us, I believe, was an encounter with Mind at Large.

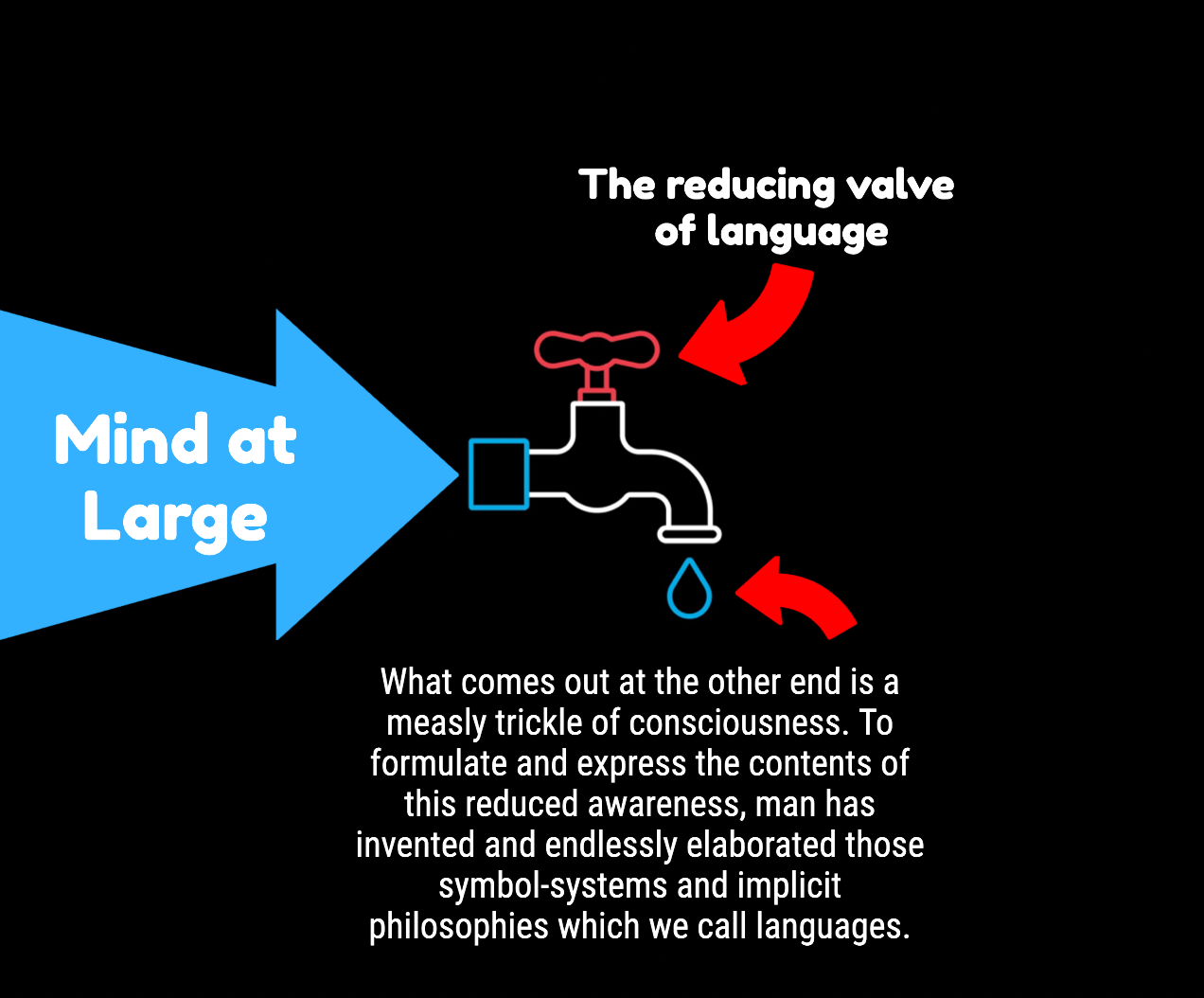

Mind at Large has to be funneled through the reducing valve of the brain and nervous system. What comes out at the other end is a measly trickle of the kind of consciousness which will help us to stay alive on the surface of this particular planet. To formulate and express the contents of this reduced awareness, man has invented and endlessly elaborated those symbol-systems and implicit philosophies which we call languages.

Every individual is at once the beneficiary and the victim of the linguistic tradition into which he has been born—the beneficiary inasmuch as language gives access to the accumulated records of other people’s experience, the victim in so far as it confirms him in the belief that reduced awareness is the only awareness and as it bedevils his sense of reality, so that he is all too apt to take his concepts for data, his words for actual things. That which, in the language of religion, is called “this world” is the universe of reduced awareness, expressed, and, as it were, petrified by language.[65]

Each of us was a “man made of words.”[66] Ironically, each of us was at a loss for words to convey what transpired. Nietzsche went back to his rented rooms and brooded while playing Wagner on the piano. He wept when his former colleague, the theologian Professor Franz Overbeck, arrived to escort him home. Jung expressed fear over the inchoate energy that compelled him to abort his research expedition to Africa. Thoreau, reduced to shouting, believed he had made contact with something vast and malevolent. Saul, it is said, was rebuked by a voice he took to be that of Jesus of Nazareth.

Each of us had a searing encounter with a presence beyond our customary phenomenological boundaries. Each of us was disarticulated by the event. What Saul called the Lord, what overwhelmed Thoreau on Katahdin, what Jung identified as something primal, demanding his attention: all of these, Rilke called the Angel.

Give his light hands nothing to hold

of your burdens. Otherwise they’ll come at night

to you, to test you with a fiercer grip,

and go like someone angry through your house

and seize you as if they’d created you

and break you out of your mold.[67]

“What we choose to fight is so tiny! / What fights with us is so great!”[68] Only someone who has gone through what these individuals experienced can appreciate Rilke’s words. I speak from firsthand knowledge. To quote Whitman, not poetically but literally, “I am the man. I suffered. I was there.”[69]

Earlier on, I invoked Rilke’s poem “The Man Watching.” Here it is, once more. Focus on the phrase “and not need names.”

If only we would let ourselves be dominated

as things do by some immense storm,

we would become strong too, and not need names.[70]

Names are the principal tool in what I call the physics of erecting or, alternatively, smashing boundaries. This has been my thesis throughout these lectures. In the next two lectures we will see a vivid example in the land of the Navajo.

Rilke’s next lines in “The Man Watching” speak to Saul and Nietzsche, and perhaps to Thoreau and Jung as well. We are often cautioned to be careful what we wish for. We must also be careful about what we wrestle with.

What is extraordinary and eternal

does not want to be bent by us.

I mean the angel, who appeared

to the wrestlers of the Old Testament:

when the wrestler’s sinews

grew long like metal strings,

he felt them under his fingers

like chords of deep music.[71]

I have remarked that Nietzsche, a pianist, went back to his lodgings and played Wagner on and off for days. When Overbeck arrived, Nietzsche performed Wagner for him. I have read that he habitually played in chords—“chords of deep music.” (Nietzsche’s relationship with Wagner was intense. It began as adoration on Nietzsche’s part, soon deteriorating into unseemly mutual public vilification. As his madness took control—ravings broken by periods of calm lucidity—Nietzsche returned to the music whose creator he had savaged.)

Whoever was beaten by this Angel,

(who often simply declined the fight),

went away proud and strengthened

and great from that harsh hand,

that kneaded him as if to change his shape.

Winning does not tempt that man.

This is how he grows: by being defeated, decisively,

by constantly greater beings.[72]

I interpreted my defeat as the gift. So did the apostle Paul. Jesus, it appears, did the same in response to the harsh hand that kneaded him in the Judaean wilderness. It is said he habitually returned to wilderness for spiritual regeneration: “When he had sent the multitudes away, he went up into a mountain apart to pray: and when the evening was come, he was there alone.”[73] Wildness was his source of power and comfort. This is indisputable. The Gospel writers who reprised the “temptation in the desert” story two or three generations later claimed he was confronted by Satan. This is moonshine; he was no more accosted by Satan than was I, in the Adirondack wilderness, or Jung in Africa, Thoreau on Katahdin, Saul on the road to Damascus, or, for that matter, Nietzsche in Turin. This son of a carpenter, this young man with an intellectual gift (recall his precocious debate with the scholars in the Jerusalem Temple)—this is the credible Jesus who emerged “proud and strengthened” from forty days in the presence of something untouchable, impenetrable, and impalpable.

This presence is also credible. David Bohm called it “wholeness and the implicate order.”[74] It is not religion; it is the way of the universe. It is physics.

And what you thought you came for

Is only a shell, a husk of meaning

From which the purpose breaks only when it is fulfilled

If at all. Either you had no purpose

Or the purpose is beyond the end you figured

And is altered in fulfilment.[75]

Eliot’s lines get to the heart of the matter—for me, Jung, Thoreau, Saul, Nietzsche. For all of us, including Jesus. “That which is only living / Can only die,” Eliot writes elsewhere.[76] Here is the credible “born again” eternal life message from the man who took seriously the unnerving, counterintuitive, yet magnificent reality of the gift. For forty days and nights, with no knap-sack granola bars or other packed-in resources, the gift of place—the gift in situ—sustained him. Which is why Jesus chose fishermen as followers. Fishermen, ipso facto, understand the gift.

And it came to pass, that, as the people pressed upon him to hear the word of God, he stood by the lake of Gennesaret, and saw two ships standing by the lake: but the fishermen were gone out of them, and were washing their nets. And he entered into one of the ships, which was Simon’s, and prayed him that he would thrust out a little from the land. And he sat down, and taught the people out of the ship.

Now when he had left speaking, he said unto Simon, Launch out into the deep, and let down your nets for a draught. And Simon answering said unto him, Master, we have toiled all the night, and have taken nothing: nevertheless at thy word I will let down the net. And when they had this done, they inclosed a great multitude of fishes: and their net brake. And they beckoned unto their partners, which were in the other ship, that they should come and help them. And they came, and filled both the ships, so that they began to sink.

When Simon Peter saw it, he fell down at Jesus’ knees, saying, Depart from me; for I am a sinful man, O Lord. For he was astonished, and all that were with him, at the draught of the fishes which they had taken: And so was also James, and John, the sons of Zebedee, which were partners with Simon. And Jesus said unto Simon, Fear not; from henceforth thou shalt catch men.

And when they had brought their ships to land, they forsook all, and followed him.[77]

The Gospel stories are obviously embellished. There is nothing surprising in this; supernatural marvels were standard fare in that time and place and are entirely consistent with hagiography. They are a distraction easily dispensed with. Our task, two thousand years later, is to move such furniture out of the room and get down to the floor joists of the Jesus narrative. Do this without prejudice, and you cannot help but arrive at the gift. I mean, the physics of the gift. The door to this inscrutable physics is language. There are others besides language, to be sure, yet language is the chief portal.

Language works both ways. It can take us into this cosmic manifold or wall us off from it. The choice is ours. Fundamentally, the choice is to name or not to name: “And whatsoever Adam called every living creature, that was the name thereof.”[78] Behold Adam’s Wall. “Adam / in Eden was the father of Descartes,” observed Wallace Stevens.[79] Descartes’s res cogitans and res extensa added brick and mortar to the wall.

Then came the double-slit experiment, reducing Adam’s Wall to rubble. Wheeler’s game of Twenty Questions affirms this. For ten thousand years our forebears have played a cosmic game of Twenty Questions in the conviction that a preexisting, manifested word (or object) was in the room. It was merely a matter of finding it with the “right” words, or other measuring apparatus. Bohr, Heisenberg, Wheeler, Bohm, Hiley, Bell, and others proved that assumption false. We are irrevocably entangled in the manifesting of whatever is in the room. There is no such thing as finding it with the “right” apparatus, because there is no it to find.

So-called primitive societies, like the ones from which Jung fled on his Africa expedition, have always known this. What’s more, they knew that the enfolding/unfolding process manifests itself only as the gift. I didn’t say as a gift; I said the gift. The gift, let me be clear, is the undifferentiated, nonsegmented Whole (David Bohm), the amassing harmony of Stevens. Notice, furthermore, that I referred to the process as both enfolding and unfolding. We are included in the enfolding and unfolding.

To put it more strongly, it is not that we as observers . . . participate in nature, but that nature participates in nature. Thus the observer is not something special. The cosmos does not need observers to function and evolve. Observation is simply a particular example of [a] general notion of transformation in which the observed and observing processes fuse in an indivisible and irreducible way. Bohr (1961) talked about it as “the indivisibility of the quantum of action.” It is not that we can never separate objects from the observing process; we can once the interaction has ceased. But during the interaction the individual becomes an intrinsic part of the whole process and becomes transformed in the process.[80]

We are not bystanders. We are sucked into the energy and momentum field of the gift (wholeness). We become something different.

______________________

[37] See my discussion of Claude Lévi-Strauss and Jean-Jacques Rousseau in note 44 [check accuracy], chapter 5.

[38] Lévi-Strauss, Totemism, 89.

[39] Andrea Moro, I Speak, Therefore I Am, 4.

[40] Hiley, “Non-Commutative Geometry,” 8.

[41] Eiseley, Invisible Pyramid, 31. As Hiley notes, “There is only one reality for both [quantum and classical] domains, and the transition occurs as the quantum potential becomes negligible. The ease with which the transition occurs in the Bohm interpretation is one of the positive advantages of this approach and thus it provides a simple way of studying the classical-quantum boundary.” B. J. Hiley, “The Conceptual Structure of the Bohm Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics,” in Foundations of Modern Physics 1994; Seventy Years of Matter Waves, proceedings of symposium in Helsinki, 1994, eds. K. V. Laurikainen, C. Montonen, and K. Sunnarborg (Gif-sur-Yvette, France: Editions Frontières, 1995), 99–118. In a 21-page offprint sent to me by Hiley, the quote appears on p. 7.

[42] Eiseley, Invisible Pyramid, 20, 32.

[43] Ursula K. Le Guin, “The Rule of Names,” in The Wind’s Twelve Quarters: Stories (New York: HarperCollins, 1975), 80–92.

[44] Le Guin, “Rule of Names,” 82–83. “The name is thus the thing so far as it exists and counts in the ideational realm.” Hegel, Philosophy of Mind, 85 (§462).

[45] Le Guin, “Rule of Names,” 91.

[46] Fairfield Porter quoted in “Fairfield Porter: Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, June 1–August 19, 1984.” The quote is taken from “Conversation with Fairfield Porter,” June 6, 1968, Archives of American Art.

[47] Theodora Kroeber, Ishi in Two Worlds: A Biography of the Last Wild Indian in North America, fiftieth-anniversary edition (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1961), 127.

[48] Kroeber, Ishi in Two Worlds, 127–28.

[49] Kroeber, Ishi in Two Worlds, 128, emphasis hers.

[50] Lévi-Strauss, Totemism, 102; Rousseau, “Essay on the Origin of Languages,” in Origin of Language, trans. Moran and Gode, 12.

[51] See note 44 [check accuracy], chapter 5.

[52] The phrase “limitless, undifferentiated awareness” is borrowed from Aldous Huxley, Island (New York: Harper & Row, 1962), 326.

[53] Le Guin, “The Word of Unbinding,” in Wind’s Twelve Quarters, 71–79.

[54] Le Guin, “The Author of the Acacia Seeds and Other Extracts from the Journal of the Association of Therolinguistics,” in Fellowship of the Stars: Nine Science Fiction Stories, ed. Terry Carr (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1974), 222.

[55] Bohm, Wholeness and the Implicate Order, 7.

[56] There is a huge literature on this current mess. Most of it, trash. The best is found in the works of the late philosopher and zoologist Paul Shepard, the anthropologist Robin Fox, and the novelist Daniel Quinn.

For a brilliant analysis of this fiasco, I recommend Andrew Saltarelli’s massive and brilliant, Leaving Home (Malone NY: K-Selected Books, 2023). “We walk down city streets assailed from every direction, every liquor store and fast-food joint, every buzzing neon letter, every billboard, big rig, and leaf-blower shrieking the same crazed question: How did this madness happen?” (Saltarelli, Leaving Home, 130, emphasis mine). “Perhaps one day we will understand what we lost,” writes Saltarelli. Frankly, I doubt it.

I remember the day Paul Shepard, Saltarelli’s spiritual mentor, confided that he considered humanity a “mistake of nature,” he put it. It was the last time I spoke to him in person. He died a year or two later. In any case, I agree with him when it comes to Neolithic man, though not Paleolithic man. Ishi was not a mistake of nature. The entire species cannot be damned for the runaway train invented by Adam and his progeny.

[57] Bohm, Wholeness and the Implicate Order, xii.

[58] Bohm, Wholeness and the Implicate Order, emphasis his.

[59] Eiseley, Invisible Pyramid, 31–32.

[60] Hiley, “Non-Commutative Geometry,” 9.

[61] In this spirit, I recommend The Great Dance: A Hunter’s Story, a film about Kalahari Bushmen hunting. The title speaks volumes. These people regard the hunt as a Great Dance. The gift suffuses the movie, despite what appears to be Christian influence when it comes to their “god” giving them wildlife to take down. The Great Dance: A Hunter’s Story, directed by Craig and Damon Foster, produced by Ellen Windemuth (Johannesberg, South Africa: Aardvark Pictures, 2000), VHS.

[62] Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil, 52. Nietzsche is often facilely labeled a nihilist, linking the claim to his ‟God is dead” idea. Here´s a crash course on Nietzsche´s thinking.

God is dead because Christianity turned him into the deity of the weak, ill, disfranchised, and poor. Christianity castrated God. He became a simpering weenie. He turned from the Old Testament God of violence and even malevolence into something wholly Good. Nietzsche dismisses this as a worthless, pitiful excuse for a deity.

Nietzsche´s chief argument is that mankind must return to the old Teutonic, Nordic virtues of strength, manliness, ruthlessness, respect for elders, family, and ancestors. Pity and humility are to be spurned and banished. The ‟will to power” is his mantra. This program is carried out by the superman. The special man, chosen by Providence, who rises to the crisis and crushes the weak and decadent. Napoleon and Cesare Borgia are among his heroes.

Nietzsche´s other idol is Dionysus. The bacchanal. The virtue of the bacchanal is disinhibition, following one´s instincts. Time and again he praises passion, instinct, and what amounts to social Darwinism, though he doesn´t use this term. The Darwinian struggle is magnificent, glorified. Decadent societies take care of the weak, poor, oppressed, sick, and dying. Christianity is the religion of the decadent mind; the religion of the low class who, frankly, deserve to be low class. Let disease and war and extermination and euthanasia carry them off! Thus Christianity is by definition nihilistic; it supports and encourages the deadbeats of the great struggle of Nature. Christianity hides behind false promises of a heaven and punishment of the oppressor.

Against this background, it is curious that his breakdown in Turin was over pity for a horse being whipped by its owner — a cart horse owned by a scumbag. Nietzsche? Pity?

[63] Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil, 51. Nietzsche used the phrase in a different context, yet it is ironically appropriate here.

Note the famous photograph (1882) of Nietzsche, the Russian-born psychoanalyst Lou Andreas-Salomé, and the poet Paul Rée, the two men yoked to a cart as horses, with Lou pretending to whip them. Both men were passionately in love with Lou. There has been considerable comment on this scene, which, by Andreas-Salomé’s account, was entirely Nietzsche’s doing. Andreas-Salomé, Looking Back: Memoirs, trans. Breon Mitchell (New York: Paragon House, 1990). I recommend Dominic Pettman, “When Lulu Met the Centaur: Photographic Traces of Creaturely Love,” NECSUS (June 12, 2015).

[64] Verrecchia, “Nietzsche’s Breakdown in Turin,” 106.

[65] Huxley, Doors of Perception, 23–24.

[66] See Stevens, “Men Made Out of Words,” 90.

[67] Rainer Maria Rilke, “The Angel.”

[68] Rilke, “Man Watching,” 121.

[69] Whitman, Leaves of Grass (1855 edition), ed. Malcolm Cowley (New York: Viking, 1959), 62.

[70] Rilke, “Man Watching,” 121.

[71] Rilke, “Man Watching,” 121, emphasis his.

[72] Rilke, “Man Watching,” 121–22.

[73] Matthew 14:23 (KJV).

[74] Bohm, Wholeness and the Implicate Order.

[75] T. S. Eliot, from “Little Gidding,” Four Quartets (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1943), 50.

[76] Eliot, from “Burnt Norton,” Four Quartets, 19.

[77] Luke 5:1–11 (KJV).

[78] Genesis 2:19 (KJV).

[79] Stevens, “Notes Toward a Supreme Fiction,” in Selected Poems, 102.

[80] Hiley, “Non-Commutative Geometry,” 10, emphasis his.

- “The Cratylus,” from The Dialogues of Plato, trans. Benjamin Jowett.[↩]