The

Island of Language

Part 1

Calvin Luther Martin, PhD

November 2, 2024

Postage stamp commemorating the Serbian poet, Vasko Popa

Contrary to what Einstein thought, non-locality (what he called “spooky action at a distance”) is real.

Prof. Reneé Weber

“Somehow you will need a picture in which the distant regions of space are coupled to one another.” Perhaps like the concept above or below.

The runaway train—again!

Praxis and its offspring:

The Machine

Goethe’s “Faust” is all about prediction and control — all about the will to power. Consider Part 1, Scene 1: “Night.” Faust, alone in his study, chastising himself for his paltry, insipid academic career. Enough of this folly, he declares. “I’ve given myself to Magic art, / To see if, through Spirit powers and lips, / I might have all secrets at my fingertips. . . . That I may understand whatever / Binds the world’s innermost core together, / See all its workings, and its seeds, / Deal no more in words’ empty reeds” (“Faust,” trans. A. S. Kline, 2003). The superman that Dr. Faust is turning into is, in fact, Sir Isaac Newton, whom Goethe despised as a charlatan and evil—the man who made a pact with the devil.

Nietzsche

“A kind of placental attachment.”

(As I imagine him)

Carlyle, like the biblical David, hurls “universal wonder” and “mystery” at science’s Goliath of “mensuration and numeration”

Goethe

Jesus

St. Paul

Greenland (in red)

What Descartes meant was, “I am a thing that speaks.”

Samuel Beckett

Nobel Prize in literature (1969)

Solipism: Self-focused.

(With thanks to BillyD.)

A Cartesian “brute”: “Nature acts in them according to the disposition of their organs, just as a clock is composed of wheels and weights.”

The Island of Language, where dwelled Europe’s intelligentsia, would claim dominion over all humanity’s Globe of Thought.

“Once upon a time there was a mistake,” begins a poem by Vasko Popa. “A mistake / So silly so small / That no one would even have noticed it.

It couldn’t bear

To see itself to hear of itself

It invented all manner of things

Just to prove

That it didn’t really exist

It invented space

To put its proofs in

And time to keep its proofs

And the world to see its proofs

All it invented

Was not so silly

Nor so small

But was of course mistaken

Could it have been otherwise[1]

The invention of the subject-object dichotomy was such a mistake. Unlike the mistake in Popa’s poem, which was ashamed of itself, this mistake invented all manner of proofs to demonstrate that the subject-object separation really, truly existed. One proof was to awaken the physics of space-time and put it to work “counterfeiting . . . the world by means of numbers.”[2]

Another was to invent a fantastical struggle between good and evil culminating, in Christian dogma, in a cataclysmic final judgment: “the last favor and the last hate.” “Such is their belief,” lamented Rilke: “great and without grace.”[3]

A third was an endless confection of ideas said to carry profound meaning; indeed, ideas that were thought to be real. Deism, theism, logical positivism, empiricism, pragmatism, rationalism, utilitarianism, nihilism, environmentalism, and so on. All are counterfeits of the real. All are ideas and nothing more. Ideas are not redwood trees, North Atlantic right whales, gannets, or spring peepers. “Ideas are men,” wrote Stevens. “The mass of meaning and / The mass of men are one.”[4] (Stevens’s insight is devastating. Paul John, the Eskimo who corrected the Alaska state biologists, pointed this out—that tuntuvak are not ideas. When he did, the entire philosophical and scientific pack of cards underpinning “civilization” collapsed within that room.)

Another was the invention of something called “history,” a solipsistic narrative of humanity on a divinely or providentially-ordained trajectory toward moral perfection and universal enlightenment, while leaving everything else, including “prehistory,” out of the picture except as backdrop.

I could go on. Altogether, the proofs invented by the subject-object blunder were not silly or small. Taken together, they amount to a runaway freight train with no brakes. (The problem is that the proofs work only in a human-centered reality-box. They collapse or are outright antagonistic to the larger-than-human sphere of reality, which, after all, is the only domain of reality that matters.)

Could it have been otherwise? Absolutely yes, if thousands of years ago, in their thirst to be masters and possessors of the earth, our ancestors had not made the fatal mistake of turning their back on nonlocality, nonseparability, and participation—the strange powers of a strange physics practiced by their Paleolithic forebears and contemporaries—and, we are increasingly forced to admit, the only sphere of reality that matters.

Nonlocality, in a sentence: two subatomic particles which have been in contact (entangled) with one another at some point in their past maintain a mysterious connection even when they are separated by vast, even cosmically vast, distances. A perturbation of one instantly affects the other, regardless of how far apart they are. “Such a tight correlation, [John] Bell proved, could only mean that the separated particles were coordinating their behavior in some way not yet understood—that each ‘knew’ not only which question its distant twin was being asked, but also how the twin answered.” So writes Jim Holt in the New York Review of Books. “By the early 1970s physicists had begun to test Bell’s idea in the lab. In experiments measuring properties of pairs of entangled photons, the pattern of statistical correlation Bell identified has invariably been observed. The verdict: spooky action is real.”[5]

A year before he died of a cerebral hemorrhage, John Bell (who is said to have been nominated for a Nobel Prize the year of his death) was interviewed by my Rutgers colleague Renée Weber, a philosopher of science. “There is good pragmatic justification for ignoring Bell’s theorem [on nonlocality],” Bell unexpectedly begins. “It may have implications, but it is about things that we don’t need to know of—about some picture of what is real at the smallest level, and we can get along without such a picture.”[6]

Weber, taken aback, is not about to let this tantalizing revelation slide by. Yes, of course we can get along “in the pragmatic sense. . . . But suppose,” she persists, “we want to understand nature as much as is humanly possible. How does Bell’s theorem change our present interpretation of quantum mechanics?”[7]

“Well,” replies Bell evasively, “if you . . . need a deeper understanding than is given by the rules for applying the theory, then I think the so-called Bell theorem is important because it tells you that the picture that you will make is very different from the traditional picture.”[8]

Fair enough. Assuming one indeed seeks a deeper understanding of nature—nature consciously witnessed and experienced by mortals—what would be very different about the new picture? “Somehow,” he vaguely enlarges, “you will need a picture in which . . . the distant regions of space are coupled to one another.”[9]

Weber already knows this. Bell is avoiding her question, which is: How does Bell’s theorem revise physicists’ understanding of quantum mechanics and, by extension, compel all of us mortals to revise our understanding of Mother Nature, yes, here on earth? (Philosophers, Dr. Bell, don’t give a damn about deep space weirdness.)

His answer was basically, “I can’t answer the second part of your question.” The fact of the matter is that John Bell had no clue how nonlocality behaves in a human-experienced world, the one Weber referred to as nature. Isn’t nonlocality, after all, supposed to be irrelevant to people, including philosophers, since it’s all about subatomic matter? I pose the question sarcastically. Doubtless Bell would have had the same opinion about the quantum potential and pre-space within which nonlocality exists. “Move on, folks. There’s nothing of interest here for Paul John and the Alaska state biologists.”

No! It’s time to put on the brakes—the brakes of this runaway train. This is the screamingly obvious lesson of the exchange between Paul John and Randy Kacyon: the spectacular collision of two kinds of physics. For 10,000 years, Paleolithic physics had no name in the lexicon of ’Ādām’s (Adam) Neolithic offspring. Ever since the birth of Enlightened Adam (see Michelangelo’s imagery on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel), the Yup’ik Eskimo way of physics was called superstition.

That era of calumny is now over; done with! It has a real name and it wasn’t fake or fantasy, after all. It’s called the quantum potential. And John Bell’s theorem fits it perfectly. So does the new field of mirror symmetry, stumbled upon by quantum string theorists and soon taken up and explored by mathematicians. It turns out that two apparently unrelated and even distant geometric shapes—or even worlds or universes—have some mysterious, non-trivial link between them. They “appear somehow to reflect each other exactly” in traits and behavior, writes physics journalist, Kevin Hartnett. It’s as if “the moment an astronaut jumps on the moon, some hidden connection causes his sister to jump back on earth.” As mathematicians and physicists learn more about this uncanny symmetry, it looks like, “not only do the astronaut and his sister jump together; they wave their hands and dream in unison, too.”[10]

None of this would have surprised Paul John and the other Yup’ik elders in the room.

It is axiomatic to science that praxis—being a shorthand for measuring something in a manner that allows the subject to predict and thereby control the behavior of a conjectured object—is what matters, especially in the world that presents itself to humans: the phenomenon we call nature. At the subatomic level, quantum mechanics and Schrödinger’s equation work fine if measurement, prediction, and control are the goal. At a human scale, classical physics (Newton’s and Maxwell’s equations) likewise work just fine, once again with the caveat that measurement, prediction, and control are the intended outcome.

What happens, however, if one’s mind is not wired for praxis? Bear with me: this is vital. What happens if one’s outlook on the earth and all that dwell therein, so-called nature, is not predisposed to measurement, prediction, and control?

The question is preposterous and risible to the modern mind, the mind molded by the Enlightenment and, above all, by Francis Bacon. There is nothing in the great books and canonical teachings of the whole of western thought that caters to its implications, with the exception of the teachings of Jesus, Plotinus, Goethe, Thomas Carlyle, and numerous other sages, mystics, literary figures, and philosophers with whom I am not familiar—all of them outliers easily dispensed with by mainstream scholars and intelligentsia, who judge Jesus et al. to be matters of theological or literary interest, which in turn is a matter of faith or literary taste. A life of full-bore, bona fide faith has little to no role in the affairs of empiricism and praxis. Piety, yes. Genuine faith, no.

“Faith” has had a stormy history in western civilization, as illustrated in the career of my namesake, Martin Luther, who built his case against the papacy on the apostle Paul’s doctrine of salvation by faith. We need to step back and clarify the matter of faith as I am using it. Francis Bacon is a good place to start. Bacon is emphatic about separating faith from praxis. “God, the creator of the universe and of you, . . . reserved for himself your faith, but gave the world over to your senses.”[11] And, “Give to faith that which is faith’s.”[12] Likewise, Nietzsche: “‘Faith’ as an imperative is a veto against science; in praxi it means ‘lies’ at any price.”[13] For Nietzsche, faith is “a form of illness. . . . ‘Faith’ simply means the refusal to know what is true.”[14]

Bacon and Nietzsche are referring of course to Christian faith. Bacon allows for Christian (ecclesiastical) faith so long as it stays in its lane, as it were, and does not interfere with the practical pursuits of science. Nietzsche damns all spiritual and religious faith, Christian or otherwise.

The problem (and irony) with Bacon and Nietzsche and countless other critics of faith is that they are referring to faith in an artifact of the agrarian imperative: faith in the biblical God. God is an invention of the Neolithic, an imposter waiting to be unmasked. While Bacon performed the inevitable and necessary task politely and surgically, Nietzsche, ever the brawler, used a hammer. In the centuries between the two men, science and secularism (the anti-faith movement) eclipsed religious piety and imperialism. The God of the ecclesiastical and political sphere died, as Zarathustra announced. Nietzsche gleefully wrote the old man’s obituary.a

Now for the important part. With the end of the reign of the Church’s God—the Renaissance God reaching out to Adam on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel—one perforce collapses the paradigm of faith, as crazy and sordid as it had become at the ecclesiastical level—which is what the Protestant Reformation was (partly) about. (Interestingly, classical Greece went through spasms of the same process many centuries earlier, well before Socrates, as the Oxford scholar E. R. Dodds explains in “The Greeks and the Irrational,” 1951.)

Exactly what people like Copernicus, Galileo, Giordano Bruno, Francis Bacon, Descartes, the French philosophes and so forth, up to and beyond Nietzsche, have meant in their quarrel with ecclesiastical faith is a question outside the scope of these lectures. Whatever these individuals meant by the word “faith,” it bears no relation to what I refer to as faith among Paleolithic societies, for whom the word is misleading and probably best set aside—except, I intend to keep using it because it’s a handy short-hand, although keep in mind its limitations. For them, what we call “faith” is more of an umbilical cord—we might even say a kind of placental attachment—with “place”: the place they live, the place they embody, the place that is sentient and conscious and takes care of them through the manifold of the gift.

Thanks to Bohm et al. we see a whole new dimension to Paleolithic consciousness—the umbilicus, as it were. We can equate this umbilicus with the presence, participation, and non-separation described by Bohm et al. in the implicate order—the “undivided wholeness in flowing movement” he ascribed in Neoplatonic fashion to the entire universe.

Which brings us to Plotinus. One might think of the umbilicus as the One (Primal Good, Primal Beauty) of Neoplatonism.

Seeking nothing, possessing nothing, lacking nothing, the One is perfect and, in our metaphor, has overflowed, and its exuberance has produced the new: this product has turned again to its begetter and been filled and has become its contemplator and so an Intellectual-Principle.[15]

We are now in a position to see Neoplatonism’s Intellectual-Principle (hand-in-hand with the Reason-Principle aka the Logos) as the Pangaea of consciousness I refer to in earlier lectures: Huxley’s “unowned awareness,”[16] Wallace Stevens’s “amassing harmony.”

It’s starting to become apparent that the ecclesiastical doctrine of faith is an absurd non sequitur, a cosmological distraction.

To David Bohm and Plotinus we can add Carlyle, who likewise tacitly speaks for the mind-not-wired-for-praxis when, like the biblical David, he hurls “universal wonder” and “mystery” at science’s Goliath of “mensuration and numeration” (singling out Bacon’s “attorney-logic”). Carlyle, a flinty Scot, refuses to surrender to science’s “huge, dead, immeasurable steam-engine” universe, “rolling on in its dead indifference to grind me limb from limb.”[17]

Goethe would be another champion of the mind-not-wired-for-praxis. Note these lines from his celebrated lecture on Nature:

She has placed me in this world; she will also lead me out of it. I trust myself to her. She may do with me as she pleases. She will not hate her work. It was not I that spoke of her. No! What is true and what is false, she has spoken it all herself. Everything is her fault, everything is her merit.[18]

I claimed the same of Jesus of Nazareth, with his Gospel—that humans are cosmically taken care of—foremost in my mind. Although it’s difficult to separate the authentic, one might say, essential, Jesus from the paper mâché Savior of the Gospels and St. Paul, it’s undeniable that the essence of the Gospel is remarkably congruent with the Paleolithic umbilicus.

To which I add this footnote. It is one of the supreme tragedies of history that the Jesus of the Paleolithic, Neoplatonic, Goethean, Implicate Order “Gospel” was ideologically abducted and forced to perform in the service of a Neolithic, sky-god religion by his feckless disciples (they never grasped what he was talking about) and above all St. Paul (who never laid eyes on the man, and, it’s been said, was suspected by some contemporaries as being the Anti-Christ). Ironically, he was executed for publicly trashing the sky-god religion that the “Gospellers” and “Paulists,” by a theological sleight-of-hand, would shortly make him head of: a resurrected Judaism masquerading as the Church of Christ. (Nietzsche had lots to say about this swindle, including, “There never was more than one Christian, and he died on the cross. The ‘gospel’ died on the cross.” And, “The Christian, this ultima ratio of falsehood, is the Jew over again—he is even three times a Jew.”[19])

Faith, whether Neolithic (ecclesiastical) or Paleolithic (umbilical), and its corollary the gift have no place in the pursuit and exercise of the “will to power,” except insofar as faith and the gift can be faked and used as a decoy or trap (Trojan horse) or other ruse in matters of state or personal advantage—in the pursuit of the will to power, in other words.[20]

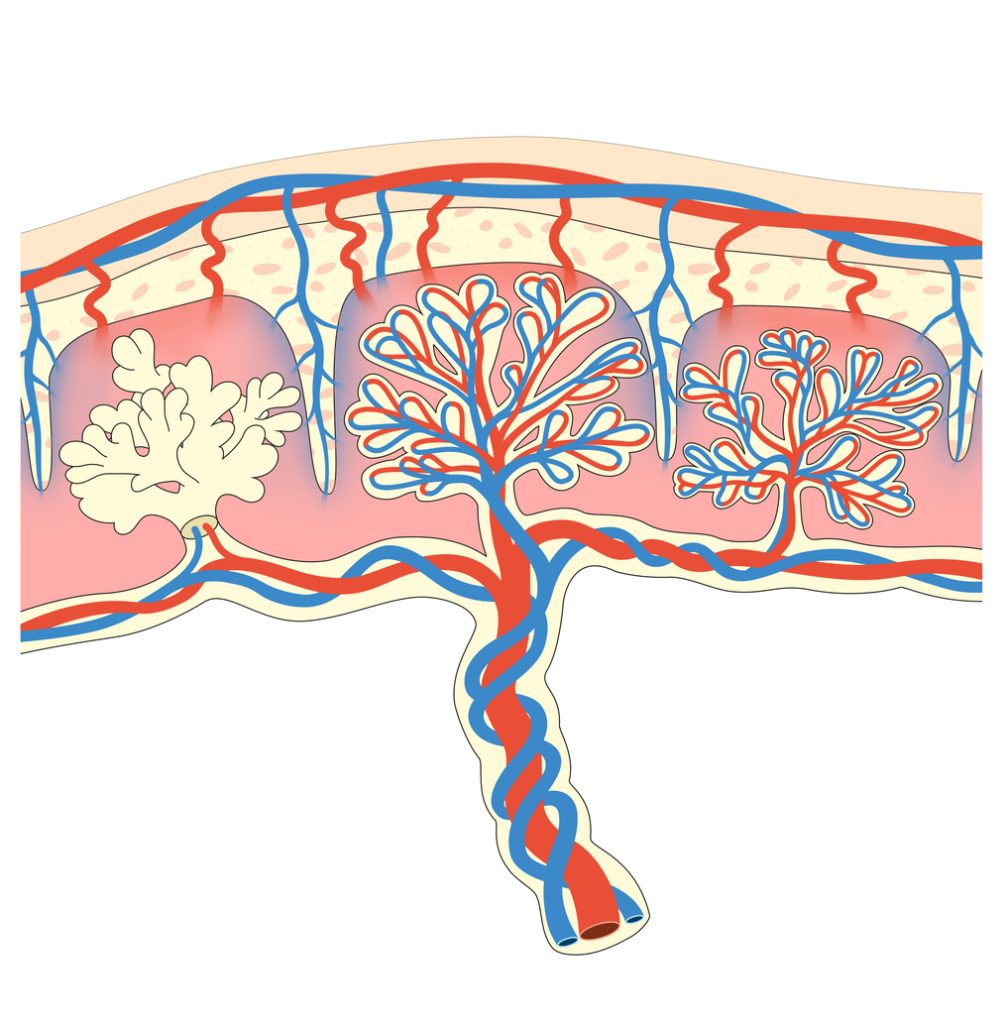

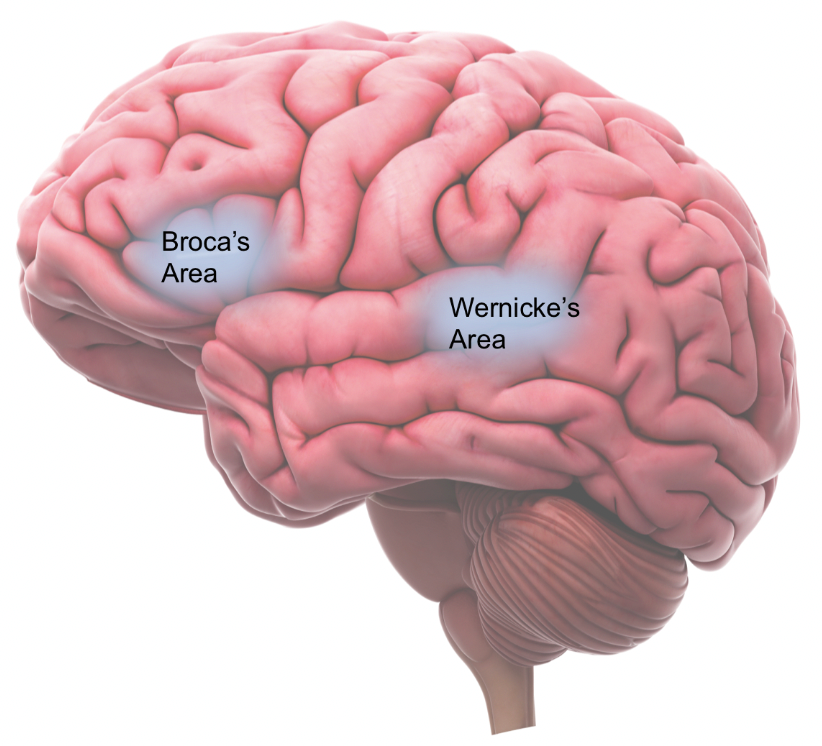

Before answering the question—‟What if one’s mind isn’t programmed to praxis?”—we need to delve into the neuroanatomy of the human mind, for the answer is more complex than one might think. The answer begins to take shape in the language comprehension and speaking centers of the human brain. By the end of this detour I will answer the question (“What if one’s mind isn’t programmed to praxis?), but it will require us first to come to terms with several issues of language and its corollary, consciousness. For this I will use Descartes and Samuel Beckett as case studies.

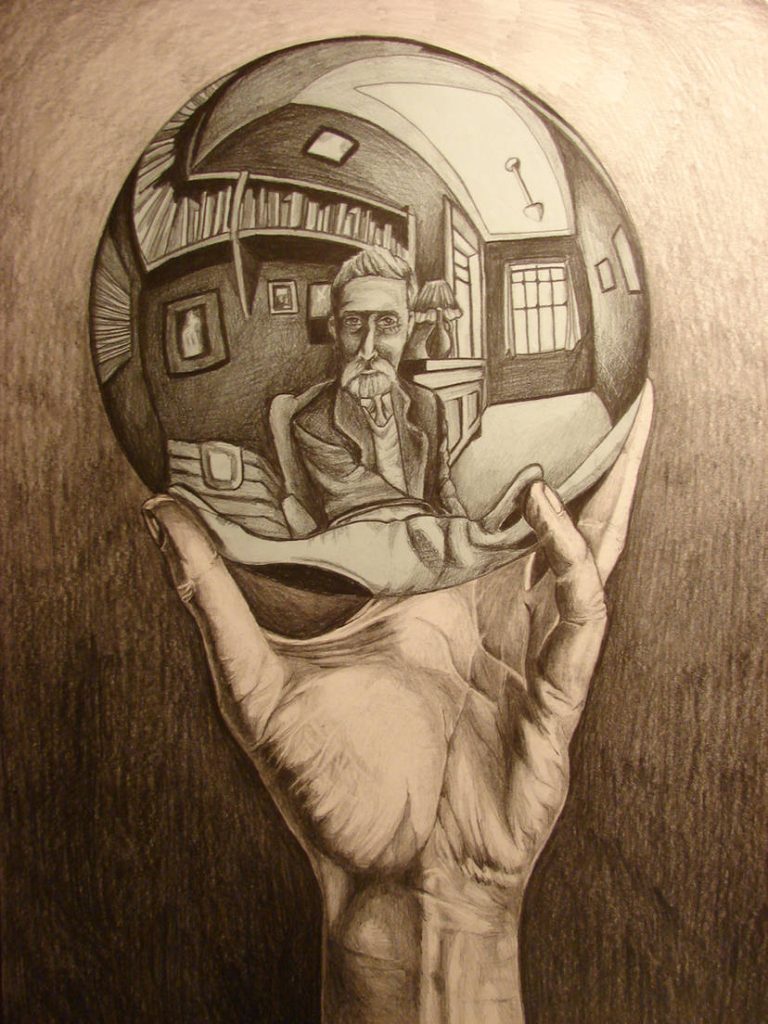

Start with your brain. Start by imagining that all your thinking is like the globe, with language being no more than a large island comparable, say, to Greenland. An island, mind you, that performs just one superficial part of the global thinking process, which, neurologists now know is rich, colorful, multidimensional, strongly visual-spatial, and emotional.

Now think of the process of putting thoughts into words, into language, as a form of translation from the Globe of Thought to the Island of Language. (A translation? Notice how we struggle to express certain things—that it takes much longer to say some things than to think them. We can visualize them in our thinking, we can know them in an instant, and yet take minutes or more to put them into words.)

Focus on the Island of Language—Greenland, as it were. Anatomically, language is comprehended by Wernicke’s area, a part of the surface of the cortex at the end of the lateral sulcus (deep fold) that separates the temporal lobe from the parietal lobe, adjacent to the hearing centers. The hearing centers process sound, and if it is language, Wernicke’s area assigns meaning to it.

Speech is a separate part of the Island of Language, formed in Broca’s area in the frontal lobe, close to the motor strip. Broca’s area finds words and syntax for the meaning you wish to convey, and passes these phrases and sentences to the motor strip for physical production. Broca’s area also assists with language comprehension, primarily, as I say, the syntactic part, and, interestingly, with the assignment of meaning to hand movements.

Both language areas are in the left cortex in right-handed people. In left-handed people, they can be on the left or right.[21]

Okay. Take a break. Go outside and have a cigarette.

It was this rich, colorful, multidimensional, strongly visual-spatial, emotional Globe of Thought that famously kept Descartes awake at night, feeling tossed like a cork on its chaotic, comedic (he phrased it) seas, a kaleidoscopic Alice in Wonderland realm of other people’s ideas and beliefs.[22] Till—Eureka!—on the Island of Language he hit upon the power he craved to tame the Globe of Thought: “I am a thing that thinks.”[23]

What he meant was, “I am a thing that speaks!” I am the man made of words, to borrow a phrase from N. Scott Momaday, who borrowed it from Wallace Stevens.[24] “After having reflected well and carefully examined all things, we must come to the definite conclusion that this proposition, I am, I exist, is necessarily true each time that I pronounce it or that I mentally conceive it.”[25]

Descartes’s existentially terrifying question “How do I know anything at all?” resurfaces as an interminable nihilistic soliloquy by the narrator in Samuel Beckett’s The Unnamable, about a wretch who is “undone by a corollary which sooner or later must attach itself to the Cartesian dualism” of res cogitans and res extensa, “namely, the incommensurability of words and things.”[26]

In lines echoing Descartes, Beckett’s narrator confides, “What I speak of, what I speak with, all comes from them”—“them” being “a whole college of tyrants” who, he imagines, conspire against him. “It’s all the same to me,” he concedes, “but it’s no good, there’s no end to it. It’s of me now I must speak, even if I have to do it with their language, it will be a start, a step towards silence and the end of madness, the madness of having to speak and not being able to, except of things that don’t concern me, that don’t count, that I don’t believe, that they have crammed me full of to prevent me from saying who I am, where I am, and from doing what I have to do in the only way that can put an end to it, from doing what I have to do.”[27]

The speaker craves silence. He begs the universe to let him be mute. Speechless. “There is nothing to express,” explains Beckett to an incredulous interviewer, “nothing with which to express, nothing from which to express, no power to express, no desire to express—together with the obligation to express.”[28] The disconnection between words and things has killed meaningful literature. “I speak of an art,” continues Beckett, that is turning from “the plane of the feasible . . . in disgust, weary of its puny exploits, weary of pretending to be able, of being able, of doing a little better the same old thing, of going a little further along a dreary road.”[29] Language and with it, consciousness, is dead, yet we must press on, for there is no other discourse for the artist who is driven to speak.

“Perhaps they have carried me to the threshold of my story,” scribbles the deranged narrator in his closing lines, mirroring Beckett’s interview. “Carried me . . . before the door that opens on my story, that would surprise me, if it opens, it will be I, it will be the silence, where I am, I don’t know, I’ll never know, in the silence you don’t know, you must go on, I can’t go on, I’ll go on.”[30]

These lectures refute the nightmarish void Beckett inherited from Descartes—the nihilism and solipsism Beckett, unlike Descartes, refused to pretend doesn’t exist. The way out—our salvation—lies in the phrase “plane of the feasible,” which is Bohm’s implicate order by another name. Against the backdrop of the implicate order—against the backdrop of the manifold of the feasible—The Unnamable’s obsession with “my story” becomes as illusory, puny, self-serving, pitiful, and meaningless as the story mechanistic physicists obsessively try to wring from the universe. Unless, that is, they allow themselves to be defeated by the double-slit experiment, as Bohm did. Defeated like the man wrestling with the Angel in Rilke’s, “The Man Watching”:

when the wrestler’s sinews

grew long like metal strings,

he felt them under his fingers

like chords of deep music.[31]

This is something physicists, novelists, philosophers, and scientists in general refuse to do: plunge headlong through the doorway we all knew as children. Witness Max in Sendak’s “Where the Wild Things Are.” Rilke revisits the doorway in many of his poems, most notably in “The Eighth Elegy.” So does Stevens in many of his poems, including “The Idea of Order at Key West,” “The Man with the Blue Guitar,” and “Anecdote of the Jar.” The doorway, in each case, to the implicate order.

If only we would let ourselves be dominated

as things do by some immense storm,

we would become strong too, and not need names.[32]

“Cogito, ergo sum”—reminiscent of Jehovah’s “I am that I am” in the Hebrew Bible[33] and Augustine’s “for we [God and I] both are, and I know that we are, and delight in our being, and our knowledge of it”b—is the new Logos, foreshadowed by Michelangelo’s Adam. Descartes’s “Cogito” is a hijacking of the Logos invoked in the Gospel according to John, which itself was a hijacking of the Neoplatonic Logos (what Plotinus would call the Reason-Principle) probably via Gnosticism (see Dean Inge):

In the beginning was the Word and the Word was with God and the Word was God. The same was in the beginning with God. All things were made by him, and without him was not any thing made that was made.

In him was life, and the life was the light of men. And the light shineth in darkness, and the darkness comprehended it not.

And the Word was made flesh and dwelt among us, and we beheld his glory, the glory as of the only begotten of the Father, full of grace and truth.[34] c

Intoxicated by the new, counterfeit Cartesian Logos, we, the people of praxis, have imagined ourselves master and possessor of our holistic thought and that of creation around us—Mind at Large, Aldous Huxley called it.[35] Master and possessor of all mind, indeed, since “brutes,” mendaciously claims Descartes, “have no reason at all. It is nature which acts in them according to the disposition of their organs, just as a clock, which is only composed of wheels and weights, is able to tell the hours and measure the time more correctly than we can do with all our wisdom.”[36]

In a gesture reminiscent of Pope Alexander VI (who donated the entire New World to Spain and Portugal), the Island of Language, where dwelled Europe’s intelligentsia, would claim dominion over all humanity’s Globe of Thought. That this conquest coincided with the physical conquest of the New World was no accident.

Once upon a time, there was a mistake—“Cogito, ergo sum”—conjured up by powerful sorcerers from the Island of Language. Could it have been otherwise?

______________________

Footnotes

[1] Vasko Popa, “A Conceited Mistake,” in Complete Poems, 119.

[2] Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil, 9.

[3] Rilke, “The Last Judgment,” The Book of Images, 127, 129.

[4] Stevens, “Extracts from Addresses to the Academy of Fine Ideas,” Collected Poems, 272.

[5] Holt, “Something Faster Than Light.”

[6] John Bell, interview by Renée Weber, 1989, transcript at https://sites.math.rutgers.edu/~oldstein/bell-weber.html#E. I have corrected punctuation.

[7] Bell, interview.

[8] Bell, interview.

[9] Bell, interview.

[10] Kevin Hartnett, “Mathematicians Explore Mirror Link Between Two Geometric Worlds,” Quanta Magazine, April 9, 2018. See also Robbert Dijkgraaf, “The Power of Mirror Symmetry,” Ideas: Institute for Advanced Study (Princeton NJ), November 17, 2017.

[11] Farrington, ‟Bacon,” p. 106.

[12] Ibid, give pagination.

[13] Nietzsche, ‟The Antichrist,” p. 140, emphasis his.

[14] Ibid., pp. 146, 100.

[15] Plotinus, give pagination.

[16] Huxley, ‟Island,” p. 329.

[17] Carlyle, ‟Sartor,” pp. 84-, 86, 196.

[18] Saunders, trans., ‟Maxims and Reflections of Goethe,” p. 213.

[19] Nietzsche, ‟The Antichrist,” pp. 128, 135, emphasis his.

[20] This is amply documented in Wilbur R. Jacobs, Wilderness Politics and Indian Gifts: The Northern Colonial Frontier, 1748-1763 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1950). In fact, the entire European exploration and colonial enterprise from the 16th into the 20th centuries functioned in large measure through the counterfeit gift.

The cargo cult phenomenon among Pacific islanders in the 19th and 20th centuries is part of the subterfuge. One sees it deployed to advantage by James Cook in the Hawaiian islands. Cook’s earnest expressions of friendship were interpreted by the Hawiians to mean the sharing of material and non-material goods. When this resulted in a the ship’s boat being carried off by his new friends, the incensed Cook arrested the head chief—a response that cost him his life. See Marshall Sahlins, Historical Metaphors and Mythical Realities: Structure in the Early History of the Sandwich Islands Kingdom (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1981). “‘They have doors in the sides of their bodies [trouser pockets]. . . . Into these openings they thrust their hands and take thence many valuable things—their bodies are full of treasure'” (Sahlins, Historical Metaphors, 18).

The point is, the counterfeit gift worked spectacularly in subverting the cosmology of aboriginal societies that operated according to the genuine gift, starting with the gift of animal flesh. Illustrations of Europeans perverting the gift among aboriginals—it’s more appropriate to call it the physics of the gift—are endless.

I recommend Herman Melville’s little-read satire, The Confidence Man: His Masquerade (New York: Dix, Edwards & Co., 1857). Melville derisively conjures up a boatload of hucksters on a Mississipi steamer named Fidèle, with each passenger swindling the other with (fake) goodwill, beneficence, honor, integrity, and trustworthiness. As in, “Possibly some lady, here present, has a dear friend at home, a bed-ridden sufferer from spinal complaint. If so, what gift more appropriate to that sufferer than this tasteful little bottle of Pain Dissuader?” (Melville, Confidence Man, 129) And, “I present you with this box; my venerable friend here has a similar one; but to you, a free gift, sir. Through her regularly authorized agents, of whom I happen to be one, Nature delights in benefiting those who most abuse her. Pray, take it” (Melville, Confidence Man, 169-170).It is Melville’s bitter comment on the rampant deceit—the absence of faith and its corollary, the gift—in mid-century America, neatly summed up in the barber’s makeshift, ad hoc sign, “No trust!” (Melville, Confidence Man, 5, 353, 367).

[21] My thanks to Nina Pierpont, MD, PhD, for this review of the neuroanatomy of language and speech.

[22] Descartes, Discourse, 19, 21–22, 58–59, 63.

[23] Descartes, Discourse, 70.

[24] N. Scott Momaday, “The Man Made of Words,” in Indian Voices: The First Convocation of American Indian Scholars, Princeton University, 1970 (San Francisco: Indian Historian, 1970), 49–62, and discussion on 62–84; Wallace Stevens, “Men Made Out of Words,” 90.

[25] Descartes, Discourse, 64, emphasis mine.

[26] Bruns, Modern Poetry, 164–65.

[27] Samuel Beckett, The Unnamable, in Three Novels: Molloy, Malone Dies, The Unnamable (New York: Grove, 1958), 304, 318.

[28] Bruns, Modern Poetry, 165.

[29] Bruns, Modern Poetry, 165.

[30] Beckett, Unnamable, 407.

[31] Rilke, “Man Watching,” 121.

[32] Rilke, “Man Watching” 121.

[33] Descartes, Discourse, 21; Exodus 3:14 (KJV).

[34] John 1:1-5, 14 (KJV). This needs a robust discussion of Neoplatonism and Christianity.

[35] Huxley, Doors of Perception, 23–24.

[36] Descartes, Discourse, 36.

- See Giordano Bruno’s scandalous description of doddering God (aka Jove) in “The Expulsion of the Triumphant Beast,” and Mephistopheles’s smart-aleck aside on the “Old Man” in Goethe’s “Faust.”[↩]

- St. Augustine, “City of God,” trans. Dods, (NY: Modern Library, 2000), p. 460.[↩]

- Interestingly, Sanskrit philosophy has a remarkably similar teaching on the “Word”: “The transformations, that is, the Universe proceeds out of Brahman, which is the Word, devoid of all inner sequence; from that involution (samvarta), in which all diversity has merged and is undifferentiated and is inexpressible, all transformations being in a latent stage. . . . This Brahman creates everything as having the nature of the Word; it is the source of the illumination power of the Word. This universe emerges out of the Word aspect of Brahman and merges into it” (Iyer, “Bhartrihari’s Vakyapadiya”). Elsewhere, “It is the word which became the worlds; the word became all that is immortal and mortal. It is the word which enjoys, which speaks in many ways. There is nothing beyond the word. . . . The Creator, mentioned in the Scripture, after dividing Himself in many ways, into manifestations of Himself, entered into Himself with all the manifestations” (Iyer, “The Vakyapadiya of Bhartrhari with the Vritti”). And elsewhere, “That beginningless and endless One, the imperishable Brahman of which the essential nature is the Word, which manifests itself into objects and from which is the creation of the Universe” (Pillai, “The Vakyapadiya”).[↩]