Equus

and the

Gift

Calvin Luther Martin, PhD

November 2, 2024

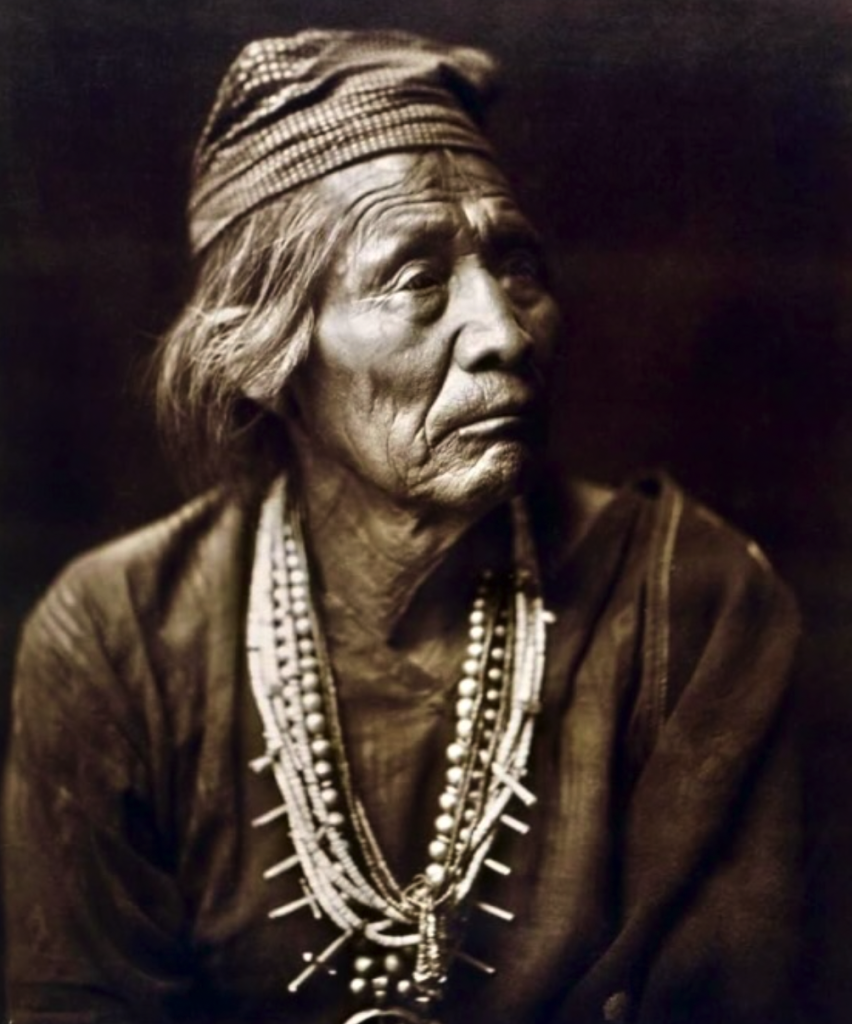

Elderly Navajo man photographed by Edward Curtis

Navajo Boy

(Re-touched photo taken by

Carl Moon, 1906)

John Keats

(posthumous)

Anthropologist voyeur

Changing Woman

(with thanks to Pistol Kitten)

“There may be no wandering from unity.”

(Ganado-Klagetoh rug)

Modern hogan

(with thanks to the People of the Fire)

The story Sapir extracted from Cháálatsoh was just this: a shell, a husk of meaning whose purpose was beyond the end the anthropologist had in mind.

Either you had no purpose

Or the purpose is beyond the end you figured

And is altered in fulfillment.[1]

Eliot’s final two lines speak to the problem of measurement I have been emphasizing throughout these lectures. B. J. Hiley, David Bohm’s colleague, illustrates the problem using a variant of the double-slit experiment. As you read, remind yourself that Hiley is giving us a glimpse into the universe as it truly is and truly works. To put this a different way, I think it’s worthwhile contemplating how the universe handles the measurement issue. There is no better way to do this than through the double-slit experiment.

We start off with a collection of subatomic particles (electrons or photons) with properties we will call color and shape. “To make things even simpler,” continues Hiley,

suppose there are only two colours, red and blue, and there are just two shapes, spheres and cubes. Furthermore, we cannot view these properties directly but need some instrument to determine the colour and another to determine the shape.

Suppose, further, that in this example our observables [color and shape] are represented by the non-commuting operators C [Color] and S [Shape], with [C, S] ≠ 0. Our objects must be described by wave functions, YR for red, YB for blue, FS for sphere and FC for cube.

Don’t worry about the math symbols. There are only two items you need to grasp. First, the order in which we do the color and shape measurements matters (this is what “non-commuting” means). Second, we are going to be dealing with wave functions, since we don’t really know what form these “particles” are in—whether they are waves or particles or, frankly, something else. (Wave functions are a mystery. No one understands what they are, just as no one understands what a quantum field is.)

“Now let us try to collect together a set of red spheres.” This is where the measurement problem originates: in the question we pose to what we perceive to be a collection of objects with a priori properties, in this instance color and shape. As I pointed out, we have no idea whether this is a “collection of objects.” Truth be told, we have no idea how this phenomenon is arranged, what form it is in, or even what it consists of, except that it appears to have energy and momentum.

When we attempt “to collect together a set of red spheres,” realize that we are proposing to divide this impalpable, untouchable, impenetrable phenomenon into separate parts. (Recall Bohm’s warning about partial questions yielding partial answers.) When we deconstruct a quantum state, as Hiley will do in a moment, we discover that we have altered the intrinsic nature of the phenomenon.

Let me put this as plainly as I can. Anything we say about the phenomenon (i.e., our “collection of objects”), or do to it in an effort to understand or know it or make it reveal itself for our purposes, changes it in ways we don’t comprehend. Remember what I said about Rasmussen and the ‟little walker,” the Bushman’s ‟rain thing,” and the San “python is an elephant” remark. In each instance the narrator refrains from controlling or forcing or otherwise bidding something to manifest itself as defined by the narrator.[2] We will see this illustrated in Navajo cosmology.

Back to Hiley, who is about to parse this quantum state. “First we measure the colour, and collect all the reds together in one group, separating them from the blues.” This color measurement is part 1. We then “take the red set and find out which of these red objects are spheres.” This is part 2, the shape measurement. Thus we have collected “a set of objects that were red according to the first measurement, and spheres according to the second measurement.” True enough.

Now for the surprise. “We might be tempted to conclude that we now have a collection of red spheres.” Nope. “When we check . . . we find half of our spheres have changed colour and are now blue!”

You see why Einstein called this stuff spooky. “This example,” interjects Hiley, “shows very clearly what we are up against in quantum theory. The central question is, how do we understand this situation?”[3]

I think the answer is: We can’t understand it. “At the deepest level, the process has neither colour nor shape,” stresses Hiley. Paleolithic societies knew this. Cháálatsoh knew this, for this is where he begins his account of horses: with nothing specified.

Cháálatsoh knew another principle perhaps even more significant: “These features arise only in relation to the process of manifestation.”[4]

Back to Sapir, who blundered upon a purpose—a quantum reality—embedded in this landscape that, in Eliot´s words, was beyond the end he figured. Sapir had no clue that the man he hired to ‟tell stories” was about to dive into the quantum reality of Dinétah and reveal a textbook quantum process. A quantum process beginning with nothing specified and proceeding through a series of non-commutative operations (namely, Turquoise Boy visiting the Diyin Dine’é: Holy Ones from whom he acquires “hard goods” and “soft goods”), where the master operator throughout is the energy of the gift. Everything in the process is done in sets and subsets of the gift. I can’t emphasize this enough. It is this fact, I believe, which makes the process work.

That´s not all. There is a second indispensable operator for the process to work: The narrator must enter the process. This explains why Cháálatsoh first sought permission from the Holy Ones and hózhó. Since the Holy Ones exist within hózhó—since they are personifications of hózhó—we can say that the narrator must enter hózhó. Which raises the question, What, exactly, does it mean to enter hózhó in the course of a narrative like the one Cháálatsoh was about to revisit? The answer to this sheds further light on my discussion of the Folding Chair Inequality.

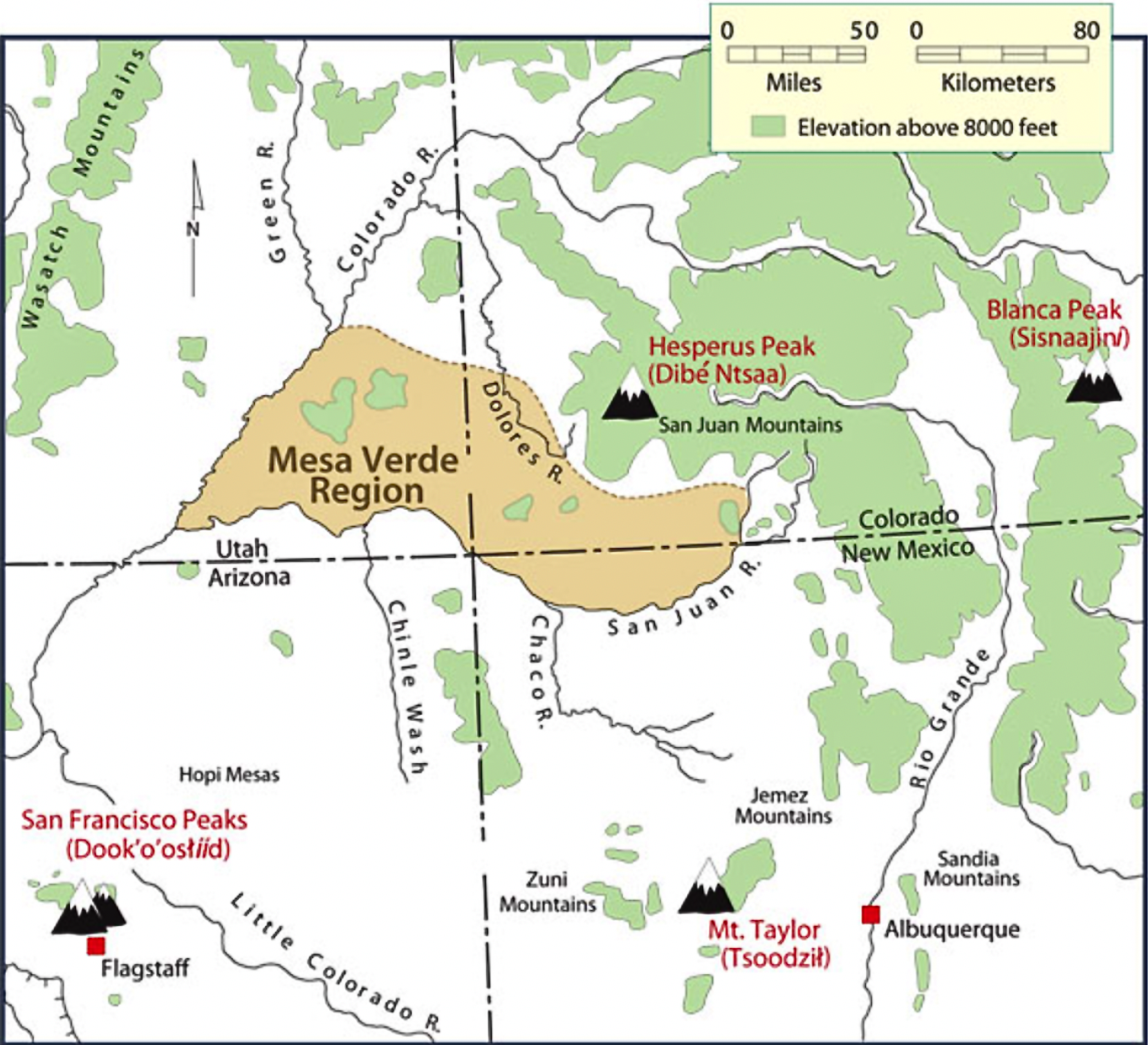

Let´s extend the question to a universal level: What, exactly, does it mean to enter hózhó regardless of specific circumstances (such as recounting a creation story)? I can´t give an exact answer. I doubt a Navajo could, either. The rock-bottom reason being that hózhó is a quantum state, a quantum phenomenon. It can´t be nailed down. John Archibald Wheeler´s phrase applies here: ‟untouchable, impenetrable, impalpable.” Besides, hózhó suffuses and embraces everything in Dinétah, which means nothing is external to it, nothing exists outside of it.

The best I can do is offer an approximate answer by examining Plato´s concept of the Idea as elaborated by his intellectual heir, Plotinus.[5] Plotinus´s exegesis on the master´s Idea bears a remarkable similarity to Navajo cosmology and hózhó in particular.

Begin with, ‟Beauty is truth, truth beauty, — that is all / Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know” — the final two lines of John Keats´s ‟Ode on a Grecian Urn.” Keats has captured the essence of Neoplatonism, certainly as Plotinus taught it. His lines likewise express Navajo cosmology perfectly. According to both cosmologies, everything is an unfolding and enfolding of Beauty. I will say categorically that in the matter of Neoplatonism and Navajo cosmology, keep in mind one word — Beauty — and you have grasped both. In both, Beauty is the beginning and end of everything. Joined inextricably and absolutely to Beauty is the Good, in Plotinus´s system of the universe. I would say the same holds true for the Navajo.

Hozho is Beauty in Dinétah. These lines from The Enneads are entirely congruent with Navajo thought:

Therefore, first let each become beautiful who cares to see God and Beauty [i.e., hozho]. So, mounting, the [individual] Soul will come first to the Intellectual-Principle and survey all the beautiful Ideas in the Supreme [hozho] and will avow that this is Beauty, that the Ideas are Beauty. For by their efficacy comes all Beauty else, by the offspring and essence of the Intellectual-Being.

What is beyond the Intellectual-Principle we affirm to be the nature of Good [hozho] radiating Beauty before it. So that, treating the Intellectual-Cosmos as one, the first is the Beautiful: if we make distinction there, the Realm of Ideas constitutes the Beauty of the Intellectual Sphere; and The Good, which lies beyond, is the Fountain at once and Principle of Beauty: the Primal Good and the Primal Beauty have the one dwelling-place and, thus, always, Beauty’s seat is There.

I also see hozho expressed in Plotinus´s notion of the Soul, as in the Soul ‟has knowledge of its own content, and this is not perception but intellection: if it is also to know things outside itself it can grasp them only in one of two ways: either it must assimilate itself to the external objects, or it must enter into relations with something that has been so assimilated.” As we shall see, this dovetails with the mechanism of assimilating the horse into the reality of hozho.

Before we get too far into this, I must draw attention to the sine qua non of ‟participation.” Cháálatsoh, I repeat, knew that participation in the narrative—engagement with it—was imperative. Absolutely unavoidable, since it was axiomatic to him that ‟the earth has perceptions and sensations and is a living being”—as Plotinus phrased it. Boas did not know the necessity of ‟participation.” The man was a bystander. A voyeur. Like his student Sapir, Boas was at best a connoisseur and at worst a plunderer. I would make the same argument about Robert Bringhurst and the vast majority of anthropologists, folklorists, literary scholars, and literary critics who purposefully or inadvertently enter the presence of this phenomenon called hozho. Barre Toelken, discussed earlier and whom I knew slightly yet significantly, was an exception. Gary Witherspoon and Noel Bennett may have been exceptions, as well.[6] I am sure there have been others, though relatively few.

I refer to ‟participation” in the manner described by Bohm and Hiley: participation in a quantum event. ‟Against doubters we cite the fact of participation,” stresses Plotinus. ‟The greatness and beauty of the Intellectual-Principle [Mind at Large] we know by the Soul’s longing towards it.” This includes the longing of the individual human soul. Elsewhere, ‟the Soul heightened to the Intellectual-Principle is beautiful to all its power. For Intellection and all that proceeds from Intellection are the Soul´s beauty.” Thus, ‟participation” as longing.

One may also call this ‟presence.” Cháálatsoh invokes it in his prayer. Neoplatonism similarly acknowledges it:

But since there is no far and near there must be, if presence at all, presence entire. And presence there indubitably is; this highest is present to every being of those that, free of far and near, are of power to receive.

Cháálatsoh had the wherewithal, indeed the longing, to receive this ‟presence entire.” I suspect it is the same presence and participation Bohm had in mind with the implicate order and nonlocality.

There was, of course, the risk of Cháálatsoh triggering the process all over again—or does it ever end?—by narrating the story. As I said in the last lecture, he didn’t seem concerned over this, since the wave function of the story had already collapsed.

With all of the above in mind, we are ready to consider the quantum process, insofar as we can analyze it from Sapir’s field notes. As I proceed, I will juxtapose the Neoplatonic explanation of certain key features of the process.

It all begins with Turquoise Boy asking his mother, Changing Woman, “How will things be created whereby [people] will live?”[7] He can’t name a specific object, because there is none. His wording is reminiscent of “the little walker”: something undifferentiated in the implicate order. In like manner, “things to be created” will be clarified and progressively manifested by the landscape’s powers, the Diyin Dine’é, although only if these powers will it. Changing Woman knows this, which is why she doesn’t answer the question.

Neoplatonism offers some interesting commentary on this first step. ‟When we speak of this First [hozho] as Cause, we are affirming something happening not to it but to us, the fact that we take from this Self-Enclosed: strictly we should put neither a This nor a That to it; we hover, as it were, about it, seeking the statement of an experience of our own, sometimes nearing this Reality, sometimes baffled by the enigma in which it dwells.” Thus, Turquoise Boy ‟hovers” about hozho, ‟seeking the statement of an experience” of his own, but not quite there, as yet.

Plotinus would insert this process, this unfolding and enfolding of Equus, within Plato´s principle of the Idea:

Yet what was that There [within hozho] to present the idea of the horse it was desired to produce? Obviously the idea of horse must exist before there was any planning to make a horse; it could not be thought of in order to be made; there must have been horse unproduced before that which was later to come into being.

If then the thing existed before it was produced—if it cannot have been thought of in order to its production—the Being that held the horse as There held it in presence without any looking to this sphere; it was not with intent to set horse and the rest in being here that they were contained There; it is that, the universal existing, the reproduction followed of necessity since the total of things was not to halt at the Intellectual.

Changing Woman sends Turquoise Boy to the Twelve Talking Gods at the eastern boundary of the hózhó of Dinétah. They know about such things, she assures him. (Curiously, she knows the answers, but refrains from disclosing them to her son.)

Here is what Neoplatonism has to say about the send-off to the Twelve Talking Gods:

But, with all its [Turquoise Boy´s] effort to grasp that prior as a pure unity, it [he] goes forth amassing successive impressions, so that, to it [Turquoise Boy], the object becomes multiple: thus in its [his] outgoing to its [his] object, it [the object] is not (fully realized) Intellectual-Principle; it [Turquoise Boy] is an eye that has not yet seen; in its [his] return, it [he] is an eye possessed of the multiplicity which it [he] has itself [himself] conferred: it [Turquoise Boy] sought something of which it [he] found the vague presentment within itself [himself]; it [Turquoise Boy] returned with something else, the manifold quality with which it [Turquoise Boy] has of its [his] own act invested the simplex.

If it [Turquoise Boy] had not possessed a previous impression of the Transcendent, it [he] could never have grasped it [the process], but this impression, originally of unity, becomes an impression of multiplicity; and the Intellectual-Principle in taking cognizance of that multiplicity knows the Transcendent and so is realized as an eye possessed of its vision.

I realize this sounds convoluted and complex, and it may require several readings to appreciate what is being said. The Neoplatonic process of discovery and realization of something unknown and unnamable — in this case, Equus — and yet, somehow, omnipresent and perhaps in a kind of superposition, is remarkably similar to the process followed by Turquoise Boy. It is significant that the Western cultural tradition, at one time, had a philosophy remarkably congruent with Navajo cosmology.

“For what reason are you traveling about, my grandchild?” ask the Diyin Dine’é upon Turquoise Boy’s arrival. Once again, his response is vague, yet interesting. “In order that by means of which [blank] live will be created, I am traveling about, my great-uncle.”[8] Notice the focus is on “traveling about” for something to be created. Whatever this nebulous thing is, it’s linked to traveling. The gods show him hard goods (turquoise, whiteshell, abalone, jetstone) and soft goods (skins from “he who lies at the water’s edge”[9] and “that which is not arrow-marked,”[10] and woven “those which are designed,”[11] etc.). Alas, “this is not what I am traveling about for, my great-uncle.”[12]

Having seen the hard goods and soft goods, Turquoise Boy can participate in the further unfolding of whatever it is he’s looking for. “I am traveling about . . . in order that we may have a means of travel.”[13] Ah, respond the gods, “that is not in existence here.” If you had asked for hard goods and soft goods—these we have. “That for which you travel about is lacking here. The rainbow is our only means of travel. The sun’s rays are our only means of travel.”[14]

They bid him visit the Twelve Hogan Gods of the southern summit. They may have whatever it is he’s looking for—or is looking for him. And so it goes, from east to south to west to north. This is more than an archetypal journey; it is the physics of the quantum potential.

From the east, hózhó has been restored.

From the south, hózhó has been restored.

From the west, hózhó has been restored.

From the north, hózhó has been restored.

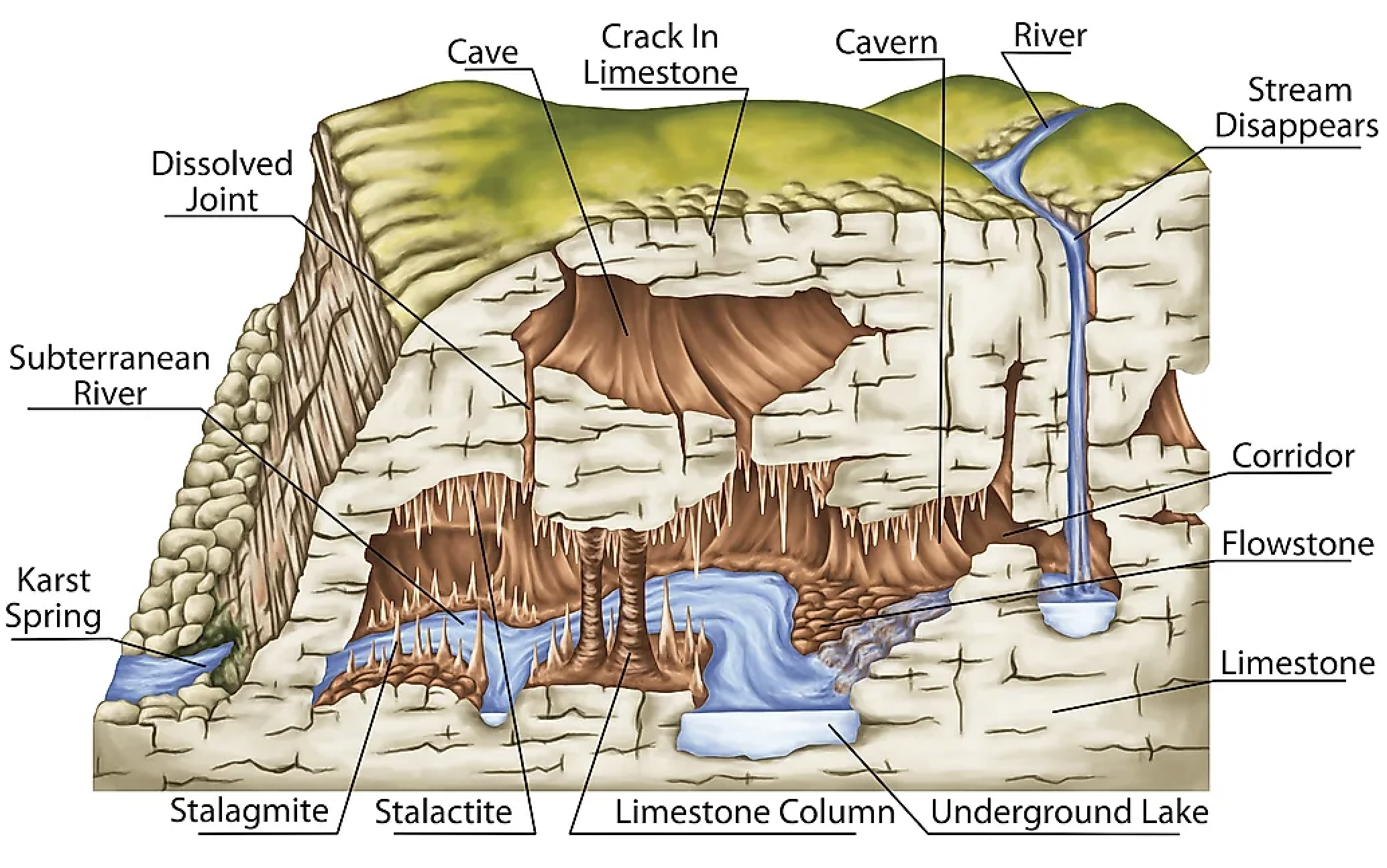

There are two dimensions of hózhó yet to be unfolded and enfolded: “With hózhó above me, I walk.” In this case it is Turquoise Boy’s dramatic encounter with the Sun and his entourage (Moon, Mist, and Mirage gods)—all on horseback.

This is followed by “With hózhó below me, I walk.” In this case, descent into a cave where Turquoise Boy encounters Mirage Man, who has heard news of the boy’s errand. Somehow, events in hózhó are nonlocal and not time-bound. “My grandchild,” begins Mirage Man, the means of travel you seek “really exists here. . . . Here they are, those with which in time to come [blank] will live.”[15] (Did Turquoise Boy go back to the beginning of creation? The question is of course wrongly put. When nonlocality is in play, time and space are annihilated.)

He opened a door toward the east, they say. The place was so large that it extended as far as one could see, they say. At the entrance, whiteshell was prancing about, they say, whiteshell in the likeness of a horse. Even its rope was of whiteshell, they say. Gracefully doing like this, lifting its foot continually, it was prancing about, they say. All of different kinds, whiteshell horses extended off in great numbers, they say. A great amount of mist-like rain falling on them continuously, they extended off in great numbers, they say. Blue birds fluttered over their heads, they say.[16]

The old god opens door after door into a universe within a universe, where whiteshell (east), turquoise (south), abalone (west), and jetstone (north) are incarnated “in the likeness of a horse.”[17]

“This now, of that which is like this, what is it that you who are Earth People can keep holy, my grandchild?” Equus Man’s question is troubling. “You who are Earth People keep nothing holy.”[18] Nevertheless, the old man dusts pollen from each of the four horses, then moves a whiteshell, turquoise, abalone, and jetstone bead in and out of the mouth of its respective creature. He places the pollen and beads in a bag and hands it to the boy. “Now that is all, my grandchild. . . . Now you may start back to your mother.”[19]

Arriving home, Turquoise Boy recounts the pilgrimage to his mother. “That for which you have been traveling,” she says, “now it has indeed been acquired, my son.”[20]

Manifestation is nearly complete. The final process is the nightlong convocation attended by the Holy Ones. Neoplatonism would call it the consummation of awareness. ‟Awareness … comes neither by knowing nor by the Intellection that discovers the Intellectual Beings [the Holy Ones of Dinétah], but by a presence overpassing all knowledge.

In knowing, soul or mind abandons its unity; it cannot remain a simplex: knowing is taking account of things; that accounting is multiple; the mind thus plunging into number and multiplicity departs from unity.

There may be no wandering from unity; knowing and knowable must all be left aside; every object of thought, even the highest, we must pass by.

In this spirit—awareness of the unity of hózhó—the gods spread the whiteshell, turquoise, abalone, and jetstone beads and pollen between skins of “that which is not arrow-marked” on the floor of a hogan, Whereupon everyone sings hogan songs, followed by horse songs. For song is wind and wind is holy.

At daybreak the bundle “moved and became alive,” Pliny Earle Goddard was told by another source, years earlier.[21] Soon “horses, their voices” are heard high up in the air.[22]

While the songs of every one of these had been sung, the dawn broke all around, they say. On the horses’ side, they kicked the covering off themselves, they say. They began to get up, they say. Just as the singing was finished, they stood up, they say. These, the turquoise horse and the whiteshell horse, they called to each other, they say. On this side, the abalone shell horse and the black jewel horse, they called to each other, they say.

This having happened, horses [Łíí’] were created [blank] the naming took place.[23]

What about the horses, one might ask, the Diné encountered from Spanish and, later, Mexican sources? Some feral, some traded or ridden north into what we call the Southwest—creatures from the conquistador space-time manifold. Apparently they had to be re-created within the pre-space plane of hózhó as I, myself, was compelled to do.

From hózhó comes Łíí’ (horse). The name connotes unfolding and enfolding. Energy. Momentum. Holy wind. The same wind you and I breathe as we stand on the rim of Canyon de Chelly.

So it must have been after the birth of the simple light

In the first, spinning place, the spellbound horses walking warm

On to the fields of praise.[24]

Before Equus walked warm onto the fields of praise, it existed somewhere else. In the Genesis story, invented by farmers for farmers, it was altogether nonexistent until it appeared full-blown out of the soil at Jehovah’s command—like a seed sown in the earth and coming up as grain. In Neoplatonic teaching, Equus existed as a Platonic Idea, emerging therefrom as an effulgent, irrepressible outpouring of Beauty. In Diné cosmology, it existed in a Neoplatonic timeless Beauty (Hozho), emerging therefrom in a labyrinthine, acoustically rich, watery, windy cave we must now visit.

_____________

Footnotes

[1] Eliot, “Little Gidding,” in Four Quartets, 50.

[2] There is a large ethnological literature on so-called hunting magic, including scapulimancy and other forms of so-called divination and conjuring. The vital thing to remember is that the hunter first joins the spirit of the game in a variety of ways: through kinship, friendship, and the medium of his spouse, who, among some tribes, behaves as the submissive game animal. In all these processes there is the understanding that game animals give themselves to the hunter. Eskimo hunters repeatedly affirmed this to me. When the gift relationship breaks down, as it did in the classic North American fur trade, the results for wild creatures such as beaver can be catastrophic.

Marshall D. Sahlins and Richard B. Lee scratch the surface of the human-animal relationship in their work. Frank G. Speck does so in detail in his classic ethnography Naskapi. I have written at length on the matter in Keepers of the Game. See Sahlins, Stone Age Economics, 1–39; Culture and Practical Reason; “Notes on the Original Affluent Society,” in Man the Hunter, ed. Richard B. Lee and Irven DeVore, 85–89 (Chicago: Aldine, 1968); and Lee, “What Hunters Do for a Living, or, How to Make Out on Scarce Resources,” in Man the Hunter, 30–48.

[3] Hiley, “Non-Commutative Geometry,” 7–8.

[4] Hiley, “Non-Commutative Geometry,” 8.

[5] See Cornford, pp. xlv, lxxiii-lxxiv.

[6] See Witherspoon, Language and Art in the Navajo Universe (1977); Bennett, Halo of the Sun. (1987).

[7] Sapir, Navaho Texts, 110–11.

[8] Sapir, Navaho Texts, 111.

[9] Sapir, Navaho Texts, 114, 462n7 (otter skins).

[10] Sapir, Navaho Texts, 122, 125; 463n23 (deerskins without an arrow mark).

[11] Sapir, Navaho Texts, 111, 495n7 (woven blankets).

[12] Sapir, Navaho Texts, 111.

[13] Sapir, Navaho Texts, 111.

[14] Sapir, Navaho Texts, 111–13.

[15] Sapir, Navaho Texts, 119.

[16] Sapir, Navaho Texts, 120–21.

[17] Sapir, Navaho Texts, 121.

[18] Sapir, Navaho Texts, 121–23.

[19] Sapir, Navaho Texts, 123.

[20] Sapir, Navaho Texts, 123.

[21] Pliny Earle Goddard, Navajo Texts, Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History 34, part 1 (New York: American Museum of Natural History, 1933), 164.

[22] Sapir, Navaho Texts, 124, 463n27.

[23] Sapir, Navaho Texts, 127.

[24] Dylan Thomas, “Fern Hill,” in Modern Poetry, ed. Maynard Mack, Leonard Dean, and William Frost, 2nd. ed. (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1950), 352.