Dinétah

and the

Folding Chair Inequality

Part 2

Calvin Luther Martin, PhD

November 3, 2024

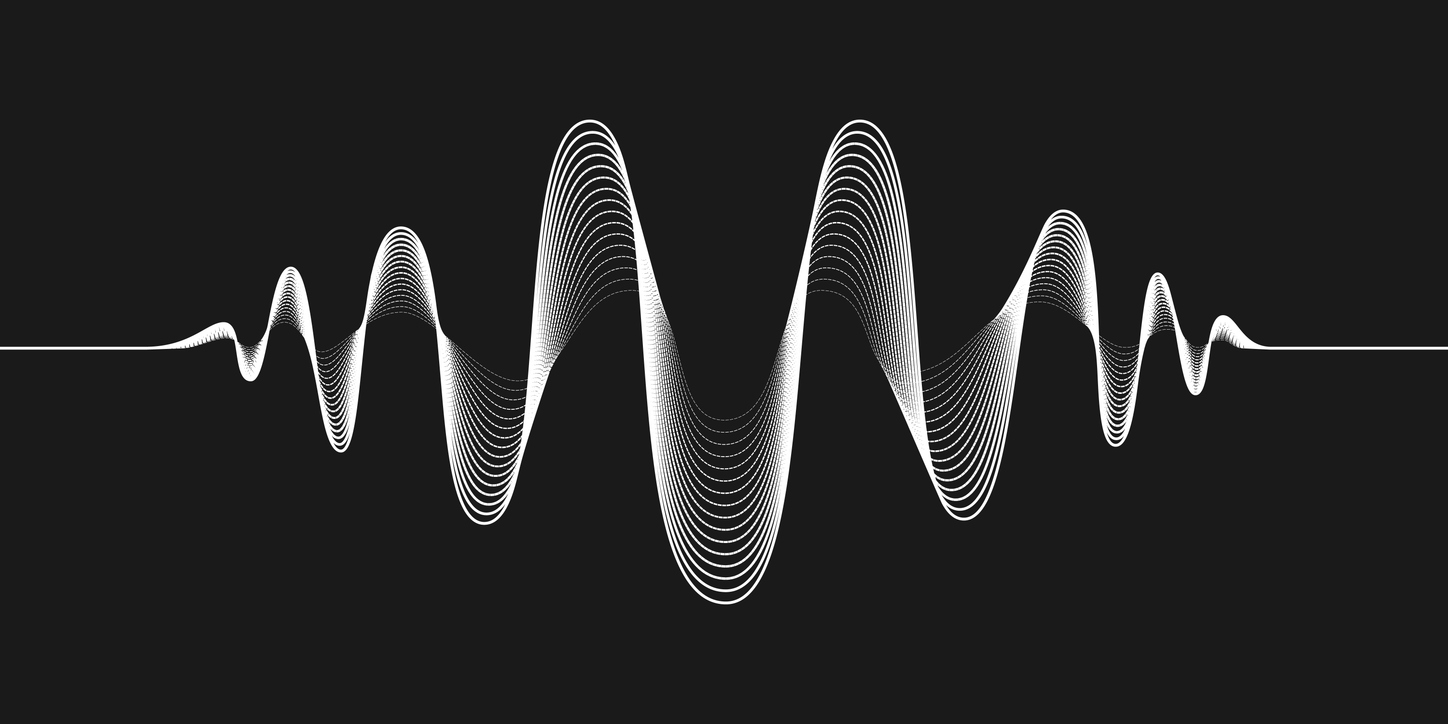

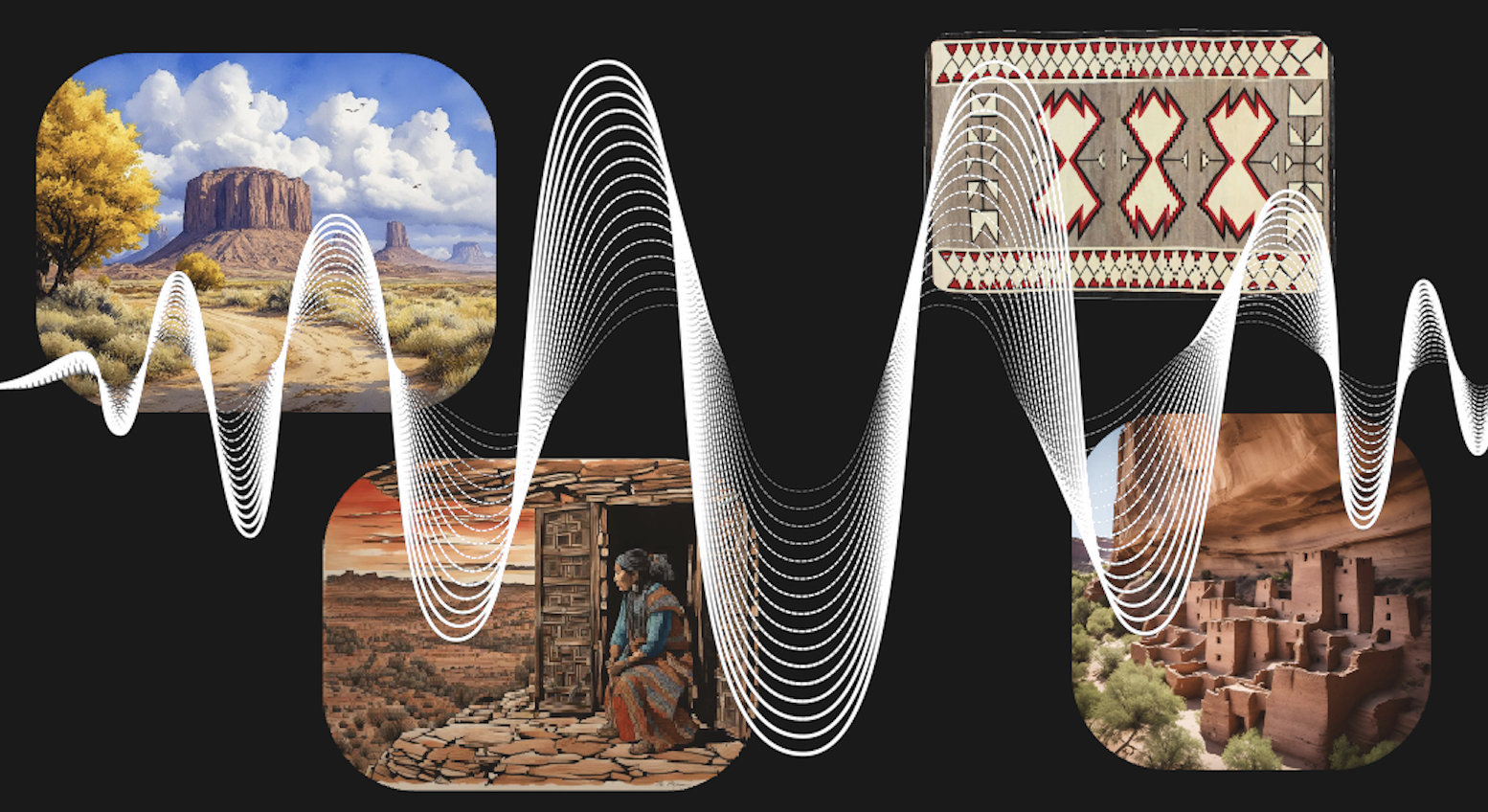

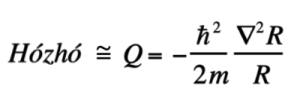

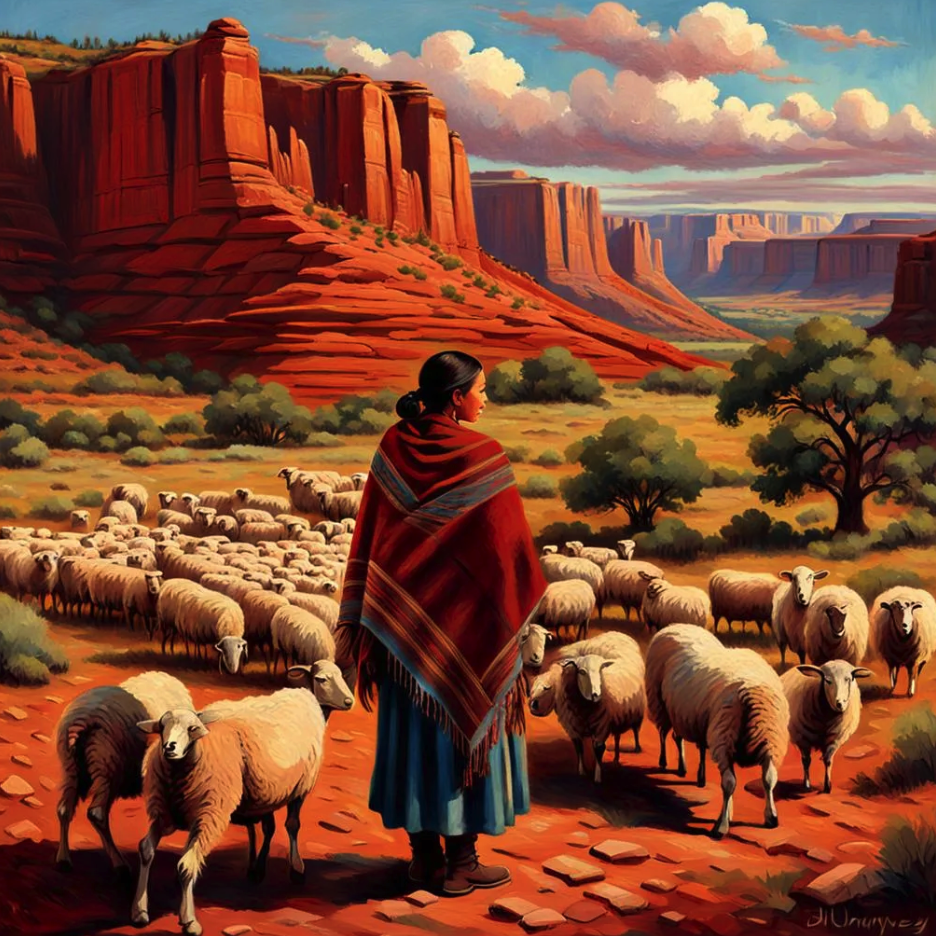

Notice the wave patterns in this Navajo rug from Chinle (pronounced “chin-lee”), the Navajo town near Canyon de Chelly. Think of these wave patterns collapsing. “Now, the stories [of] the different things that exist, all of the things by means of which [blank] live, have disappeared,” Cháálatsoh explained to Sapir.

The role of humans is to keep hózhó’s wave function intact by participating in and being transformed by it.

Prof. Barre Toelken explaining why he destroyed the “Yellowman” tapes

The folding chair fallacy of “oral literature”

Prof. Franz Boas disporting himself in Inuit clothing. He could put on these furs and skins and yet he never understood them. Basically, he whipped them out like a folding chair.

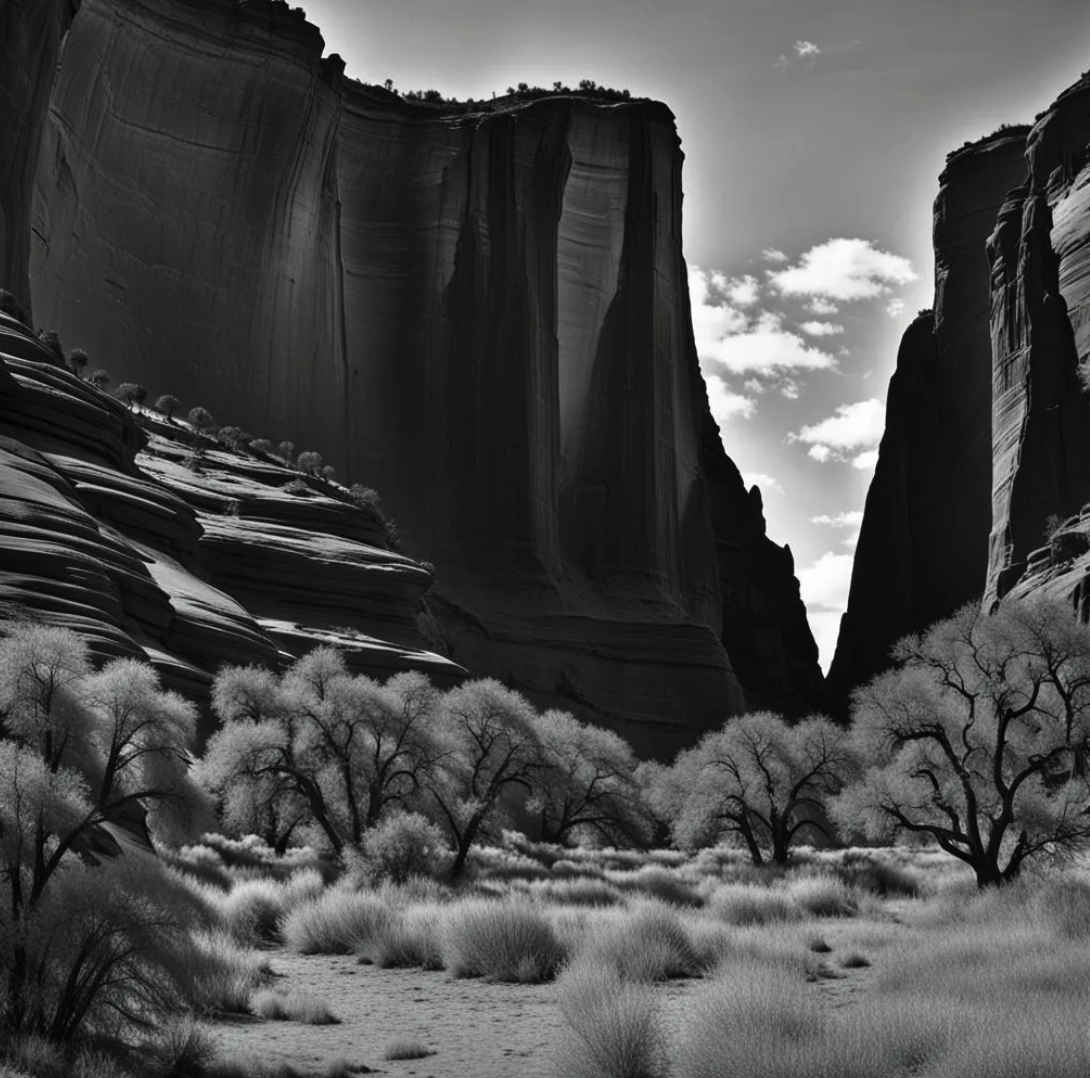

Join me again at Canyon de Chelly and think in the thought of the wind. Breathe the breath of another nature while I tell you about something that happened to me in an arroyo not far from here. What I’m about to say has nothing to do with literature, linguistics, myths, tales, legend, ethnology, or bridges, doors, or partway measures. It has everything to do with Cháálatsoh’s most important revelation: “These things,” in this case the emergence of Equus, “took place at the place called sisna·te·l. The old men’s stories began there. These [stories] have all disappeared with them,” Cháálatsoh softly explained to Sapir.[19] “Now, their stories [of] the different things that exist, all of the things by means of which [blank] live, have disappeared with them.”[20]

Bear with me; I must explain a little more before I tell you my own experience. Stories among the Navajo are beings in their own right, wet with the breath of the narrators they ordain. The stories Cháálatsoh referred to didn’t vanish so much as they collapsed. They became silent when the wave function of hózhó collapsed.[21]

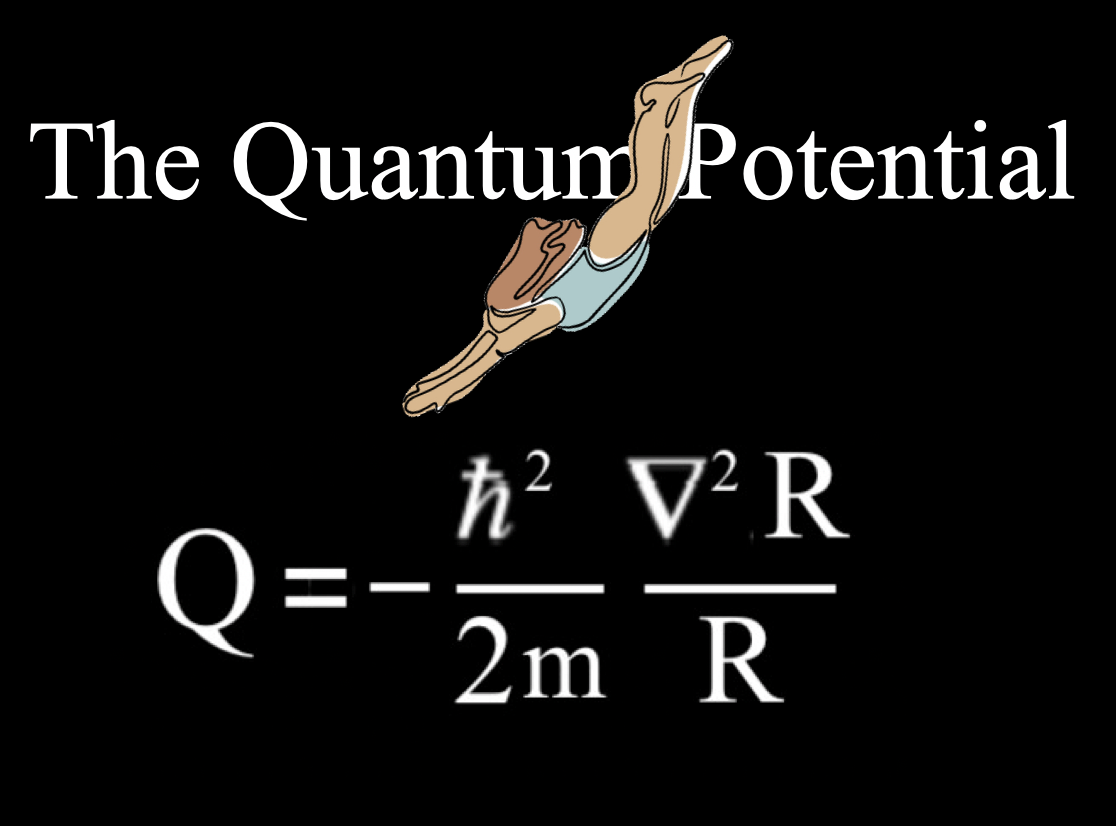

Think of the phrase są’ah naagháii bik’eh hózhó as a non-space-time physics, where the spoken-and-breathed word hózhó is the rough equivalent of Q (the quantum potential) in the Bohm-Hiley equations.

If the Navajo have a word and principle to match Bohm’s implicate order, it is hózhó. Everything that moves or breathes, and is conscious, and stands in good relation to all that is beautiful, exists by the powers of hózhó. This includes mountains and stones, plants, colors, rain, the four directions, the seasons, times of day, food, wild things, jewelry, weavings, and everything humans think and do. The role of humans is to keep hózhó’s wave function intact by participating in and being transformed by it.

In the beginning was hózhó.

And hózhó was with Dinétah, and hózhó was Dinétah.

The same was in the beginning with Dinétah.

All things were made by hózhó, and without it was not anything made that was made.In hózhó was life, beauty, perfection, goodness, balance, harmony, order—and these were the light of the Diné.[22]

In an arroyo near where we are standing, I inadvertently became part of this wave. I now know it was hózhó.

hó: “this place.”

zhó: “perfection, similar to a flower opening its petals.”[23]

What I tell you, below, is from a longer version I published years ago.[24]

It was a place given over to winds; winds seemed in control of what transpired here now. Before winds, it had been water, tumultuous rivers of silt that over the eons had sandpapered this slit into the high plateau, sculpting it into fantastic shapes and eddies. Moving always deeper into the earth, as though to lay bare its powers. Here humans had journeyed and set down over the millennia, during the age of water; the Anasazi, Ancient Ones, had built their eerie cliff dwellings farther up the canyon, downstream, as it were, from where I entered it. Upstream—although the bed was bone-dry when I visited—the canyon stopped in a box. Dead end: the sandy, pebbly riverbed was strewn with empty bottles—of Garden Deluxe, mostly, the cheap California wine popular among those contemporary Navajo who can no longer be a part of it.

Chiseled into a transverse ridge on the arroyo floor was a row of figures. Petroglyphs: a hope, a dream. A communication: rabbit tracks, hooves, and a horned serpent. Humanity beseeching the powers of place for rain (for the river to come again), for game. The sacred game etched into the land at just the correct spot. I knew it for the place of power and illumination that it was. And so I walked softly, even while realizing that I was bereft of effective communication with it. My deepest impression was that I was intruding; lacking conversation in these matters, I sensed I was out of category. I had noticed the carefully piled stones and other signs of recent human meditation under a cliff overhang a short way off from the glyphs. Some contemporary of mine, Navajo no doubt, was still fluent in these powers.

On the reservation, it was a place that had not yielded to the denaturing forces of my civilization’s speech. I knew I was being observed. The words of the magician snaked in and out of my consciousness: “It has become clear to me that perception has to be understood and recognized as a reciprocal exchange. When we see things we are also being seen by them. When we hear things we are also being heard. Perception is a type of communication that precedes language.” I liked that; I felt sacred; I felt I was communicating on the farther side of language, the place where language is born. There was nothing for me to say, audibly. Nothing for me to fashion, as the Navajo seeker recently before me had done; my hands were skilled only in the service of strangely alien errands. I stood in a place of palpable powers of earth, an intruder, and was deeply ashamed and, yes, frightened. This was a place of enormous meaning to me, and I felt lost—yet, in some ineffable way, felt I should stay.

So, staying, I knelt down on top of the smooth bedrock, slowly tracing its figures with my fingers and hands, feeling for their grace. “Traditional magicians seem to be able to flood the world which surrounds them with their imagination, to let their imaginations out. . . . If we have a creative imagination then the world itself must be filled with imaginations, not just human imaginations but the imaginings of all the other creatures around and the plants and the trees.” The day before, I had played the piano in the mission church in the village nearby, hymns to a Middle Eastern sky god who seemed to me almost ludicrously out of place in this landscape. The minister had heard that I could play, and implored me to. Fingers that could play hymns to an incongruous neolithic deity now sought to know the song of these pecked images. All I heard were the sighs and whispers of windsong here and there, fingering the canyon walls around me, ceaselessly sculpting minarets and flutings into the pliant rock. I thought of words as sculptors of space, as turn-keys: liberators or jailers of the powers about us. The wind was certainly a better musician than I, releasing powers to which my culture was oblivious. Perhaps because I am something of a musician myself, and a canoeist, I have always been attentive to winds.

I had hiked this canyon two days before with my wife, Nina, and another couple, and on the way back she had suddenly stooped down and plucked a still perfect arrow point from the sea of pebbles and smoothened stones that form the canyon floor in the vicinity of the glyphs. The four of us spent the next hour scouring the area for more, in vain. Alone now, I was in a far different frame of mind; I was in search of a theophany which, from the previous visit, I detected was still here, and might, I halfway wished, teach me something. Might speak or sing to me. It was the closest I have come to a vision quest. “In order to touch those, I believe it’s necessary to let out our imagination, to breathe it out, to cough it up if you will, to take all the work we’ve been doing on our interior psyche, all our spiritual work, and breathe it back into the space that surrounds us, and then we’ll find that that is in fact where the psyche lives. . . . That is the magician’s secret, that the spirits are right there if you would only recognize them.” Here and there in the distance a dust-devil coalesced and danced. In the fullness of time. “After working this way for many years I have begun to get a sense that perception is a very active and engaging work by which we constantly move out of ourselves through our eyes, our ears, our mouths, into the world and dance in that world, and shape it.”

Perception: being seen and heard by what I saw and heard. The idea suddenly snapped into place, into a place that fit it: here in this canyon. My sensations of being watched, of my trespass, of unease, were the reciprocal exchange my magician friend had been talking about. I straightened up and stepped away from the petroglyphs, idly casting my eye over the pebbly floor, wondering whether there might be another projectile point lying hereabout. And as I did, I had the gathering realization that such a thing would find me, but only if I imagined myself into its flesh first. I found I could let my imagination out and into this object; I could become a part of it.

And there it lay, at my feet: white and flawless save for a small chip at the tip. I picked it up and welcomed it; we seemed to be two sentient beings, joined.

Just as I cradled it in the palm of my hand I half noticed the faint wind of a dust-devil gathering behind me. In an instant there was a terrific report, like the sound of a gunshot immediately at my back, and I whirled around. There before me stood a whirlwind being, in stature, as best I recollect, slightly taller than me. Confronting me. The Visitor? Who can know these things. I felt I was being interrogated; I felt guilty and vulnerable holding this lithic in my hand. Was this the Keeper of the Artifice? The Spirit of Place? I had deliberately squeezed my imagination through an aperture and entered the spiritual dimension of this canyon; I had willfully asked to be found by a sacred object—and had been. Was I to be surprised at finding myself face to face with a wind spirit? I wasn’t, yet I was. I had been unprepared—that was it. What I said—yes, I spoke as best I could, a word and gesture of respect—seemed to come forth of its own volition. And with that the apparition whirled away to the rim and vanished.

I tried to stay, to dismiss it and carry on with what I had been doing. But what I had been doing was done. It was over, metaphysically. There was an immense, even crushing, sense of closure. I knew I must go; I had the sensation of being ejected. Buttoning the arrow point into my shirt pocket, I quickly walked out. Had the canyon closed up behind me, I would not have been surprised.

We were to leave soon; Nina, in the final year of medical school, was being reposted to the Indian Health Service Hospital at Shiprock. I am not a collector, in fact, quite the opposite. Even so, in this instance I had the impression that one could not even hope to possess this thing of that wind canyon. It belonged out there; it made sense only there, on that holy ground where I had stood; it was part of place. So, shortly before leaving, I took it back to that wind place; spoke to it, thanked it for its lesson, caressed it, and returned it.

This is the appropriate context for understanding the exchange between Cháálatsoh and Edward Sapir. The old man was telling Sapir that this wave function had collapsed.

The “stories [of] the different things that exist, all of the things by means of which [blank] live, have disappeared.”[25]

Is this why Cháálatsoh agreed to share the collapsed stories with Sapir: hoping to preserve them, somehow, in print? Possibly. I once had a celebrated Yup’ik storyteller insist that I digitally record a long narrative he suddenly decided to tell one day.[26] Unlike Sapir, I wasn’t asking for stories. In fact, we were talking about something unrelated (I thought) to the story he told. I still have his story on my computer, roughly translated by Charlie Kilangak, the puffin from Emmonak. I am at a loss over what to do with it, since it is uncoupled from the power of that place—from yua, its spirit.

The folklorist Barre Toelken faced a similar dilemma with tape recordings of stories he collected from a Navajo named Yellowman. Upon the man’s death, Toelken found himself confronting a version of the Folding Chair Inequality.[27] He resolved the crisis by destroying the tapes in his possession, while leaving a copy with the man’s family. Yellowman’s voice and words would remain where they belonged, in the implicate order of Dinétah.

Cháálatsoh was obviously conflicted about revealing stories to Sapir, for, before doing so, he made an elaborate, detailed prayer in Sapir’s presence, notifying the Diyin Dine’é (Holy Ones) of his intentions. Here is Sapir’s translation. Note the frequent invocations of hózhó (“beauty”) and są’ah naagháii bik’eh hózhó (“that which goes about at the rim of old age”).

This day I say that I have told about “that which goes about at the rim of old age,” I say that I have told about “that in accordance with which there is beauty.” I say that I have told about the Pollen Boy, I say that I have told about the Corn Bug Girl. The Earth, my mother, the Black Sky, my father, the Sun, my father, the Changing Woman, my mother, the White Shell Woman, my mother, the Talking God, my great-uncle, the Hogan God, my great-uncle: this day I say that I have told my story in a good way.

The Americans, being my younger brothers, I have told my story to them. That I shall be “that which goes about at the rim of old age,” I have told my story. That I shall be “that in accordance with which there is beauty,” I have told my story.

That before us there being beauty as we shall walk about, we have told our stories to each other. That behind us there being beauty as we shall walk about, we have told our stories to each other. That below us there shall be beauty, we have told our stories to each other. That above us there shall be beauty, we have told our stories to each other. That all about us there shall be beauty, we have told our stories to each other.

That our speech will become beautiful, we have told our stories to each other. That out of our mouths there will come beauty, we have told our stories to each other. That we shall walk about in beauty, we have told our stories to each other. That we shall walk about being “that which goes about at the rim of old age,” we have told our stories to each other.

That today we are the children of the Earth, we have told our stories to each other. That we are the children of the Black Sky, we have told our stories to each other. That we are the children of the Sun, we have told our stories to each other. That we are the children of the White Shell Woman, we have told our stories to each other. That we are the children of the Changing Woman, we have told our stories to each other. That we are the grandchildren of the Talking God, we have told our stories to each other. That we are the grandchildren of the Hogan God, we have told our stories to each other.

Let there be beauty indeed, let there be beauty indeed, let there be beauty indeed, let there be beauty indeed.[28]

Robert Bringhurst calls Cháálatsoh’s prayer oral literature. He means something he can whip out anywhere, like a folding chair. “Since the prayer has never, so far as I know, been published in current Navajo orthography,” he adds in a footnote, “I give it here in full—though what is needed for understanding is, of course, the sound of the words, not their visual representation.”[29]

No, it is not literature; it is something enfolded within są’ah naagháii bik’eh hózhó and hózhó, exactly as the old man keeps saying, over and over. And whatever są’ah naagháii bik’eh hózhó and hózhó are, they sure as hell ain’t literature, Mr. Bringhurst, especially the folding chair variety you have in mind.

And, no, what is needed for understanding is not the sound of the words. In fact, there is no understanding this, any more than one can understand nonlocality and entanglement within the quantum potential. “Understanding” occurs only in the physics of space-time, the plane occupied by Bringhurst, Sapir, and Boas. Cháálatsoh jettisoned space-time via these narratives. So did Boas’s narrators on the Northwest Coast, as revealed by these otherwise enigmatic anecdotes:

My Tsimsian has deserted me, and so far he has been the best one I have had. From experience I should know that such things happen.

The stories are in part completely senseless, and I became quite stupefied.

It reminds me so vividly of the Eskimo—they also ran away in the middle of a tale.

A woman started to tell me the story of the thunderbird, but she did not get very far. She claimed to have forgotten the most important part.

How do you say in Tsetsaut: “If you don’t come, the bear will run away”? I could not get him to translate this. He would only say, “The Nass could be asked a thing like this; we Tsetsaut are always there when a bear is to be killed. That’s why we can’t say a thing like this.” I also asked him, “What is the name of the cave of the porcupine?” His answer was only, “A white man could not find it anyway and therefore I don’t have to tell you.” Thus it goes all the time.

The bowls, however, are no longer here. They are in the museums in New York and Berlin. Only the speech is still the same. In the same way a child was supposed to be named, and they said [text missing], but these are only words. It is strange how these people cling to the form though the content is almost gone. But this still makes them happy.

People “deserted” and “ran away” from Boas, they “forgot the most important part,” gave evasive answers, refused to insult bears and porcupines by talking about them, and “clung to the form though the content was almost gone” because they were straddling two different physics. One, the enfolding/unfolding energy-momentum manifold described by Bohm et al., was clearly collapsed or in the process of doing so. The other was the alien space-time manifold let loose by Europeans. The natives, who appear wraithlike in Boas’s letters and diaries, were in free fall from a world resonant with quantum potential and its corollary, the gift, into the incomprehensible subject-object world of measurement, prediction, and control—the physics of praxis.

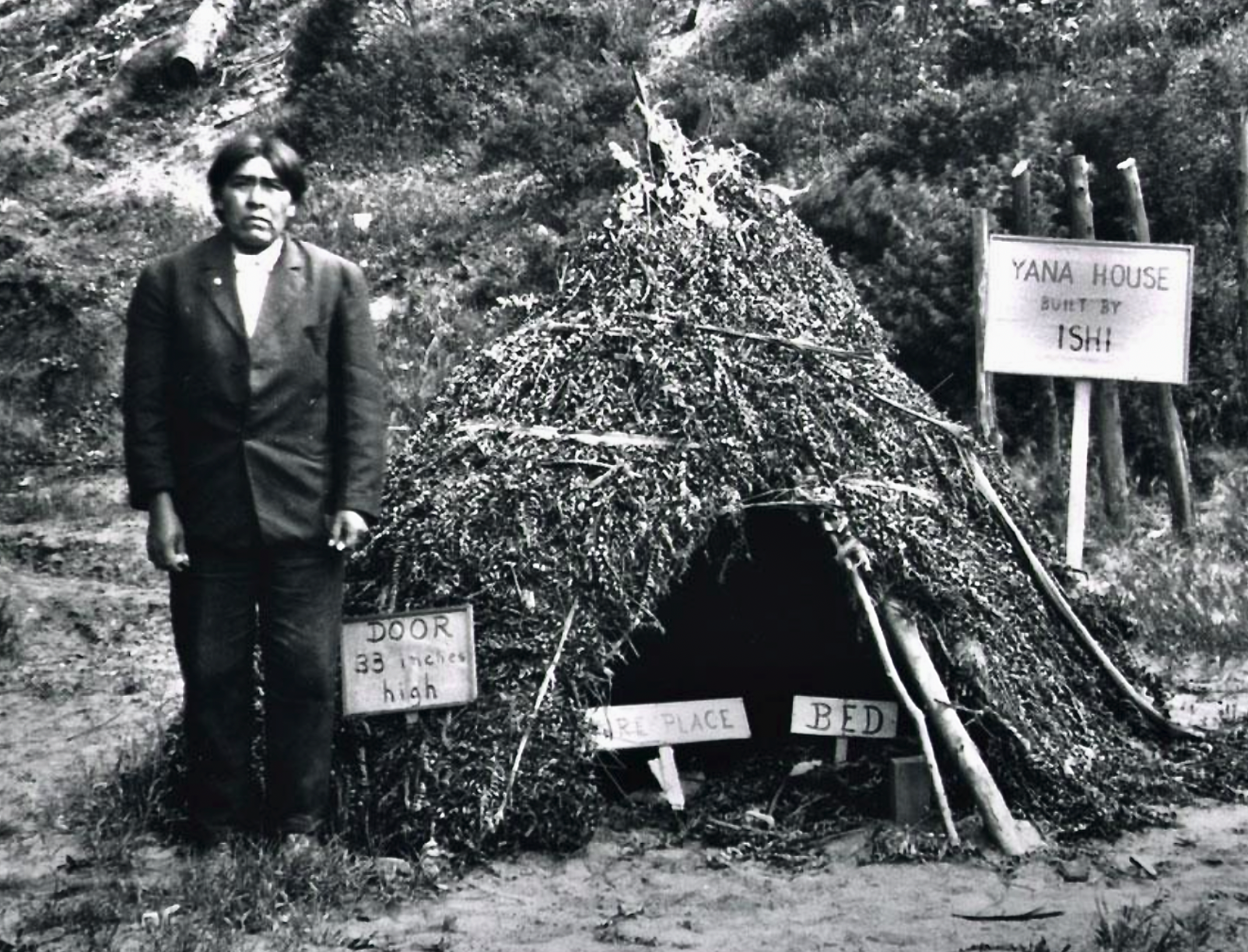

Ishi neatly embodies the issue. What was the essential man whom Kroeber clothed, bedded, and fed three meals a day at the museum? Kroeber took him camping to find out. Back into the wilderness they went, Ishi and the cream of American anthropology, the former a specimen, the latter taking notes. What the anthropologists learned was, not surprisingly, anthropology. This, of course, pleased them. And the wild man in trousers (costumed in breechclout for the camping trip) was happy to perform in anthropology.

It didn’t occur to the distinguished professors that the man had become orphaned from the enfolding-unfolding implicate order sometime before he turned up near Oroville. Which is why he resolved to leave the bush in the first place and walk into Sheriff J. B. Webber’s arms.

It is not enough to say he missed his family, or was alone and starving, destitute, and grieving. All of it undoubtedly true, but, as I say, there was more. Where the wild things are—can we call it this?—no longer functioned for him. He revealed this on the camping trip with the professors; the wilderness (as we call it) was strangely silent, remote, and uncommunicative. He expressed no desire to remain. He made it clear he wanted to be returned to the janitor’s garret at the museum.

Something portentous had happened to him. The “exact connection” had broken. Ishi illustrates what I call the first law of conquest: the physics of space-time (praxis) always collapses the physics of the quantum potential (the gift). Kroeber took a man born of the gift back to the place where the implicate order had once prevailed, but no longer did. Ishi knew this. In the eerie silence, all that was left for this man was the praxis of anthropology. Ishi knew this, too, and accepted it. At least he had the satisfaction of leaving his name there.

Long ago I published a book on this collapse. “Indians themselves were acutely aware of it,” I wrote,

as when a group of angry [eastern subarctic] Algonkians confronted [the French Jesuit priest, Father Paul] Le Jeune and denounced Christianity as a malefic influence. “ ‘It is a strange thing,’ said they, ‘that since prayer has come into our cabins, our former customs are no longer of any service; and yet we shall all die because we give them up.’ ‘I have seen the time,’ said one of them, ‘when my dreams were true; when I had seen Moose or Beavers in sleep, I would take some. When our Soothsayers felt the enemy coming, that came true; there was preparation to receive him. Now, our dreams and our prophecies are no longer true—prayer has spoiled everything for us.’ ”[30]

Frank Speck witnessed a similarly tragic commentary while interviewing an eastern subarctic Naskapi named Basil on a drum’s ability to warn its owner of danger:

In commenting on this story, Basil . . . added his own views by saying, “But I don’t believe in that now. It all belongs to the olden times. It is what we are taught to call the devil, perhaps. The times have changed. With the coming of the whites and Christianity the demons of the bush have been pushed back to the north where there is no Christianity. And the conjuror does not exist any more with us, for there is no need of one. Nor is there need for the drum.”[31]

The Indians who berated Father Le Jeune didn’t consider his prayers to be literature. They were a force of nature. Physics, in other words. The Father, we are told,

remonstrated with them, that if one did not teach them . . . they would burn eternally in Hell, and that the danger of their Salvation obliged us [Jesuits] to urge them. But the majority became still more obstinate, and were furious with spite against the Father, and said that he was a greater sorcerer than their own people; that the country must be cleared of such; that they had clubbed three sorcerers at the island [Montréal? Allumette?], who had not done so much harm as he. There was some fear lest they should carry out their evil thought: but the Divine goodness did not permit it—on the contrary, it drew great benefits from their malice.[32]

Neither did Cháálatsoh consider his prayer to the Diyin Dine’é to be literature. He knew it was a force of nature.

Centuries later, on the other side of the Atlantic, Carl Jung was told the same story heard by Speck and Father Le Jeune. “One time we had a palaver with the laibon, the old medicine man. He appeared in a splendid cloak made of the skins of blue monkeys—a valuable article of display.”

When I asked him about his dreams, he answered with tears in his eyes, “In old days the laibons had dreams, and knew whether there is war or sickness or whether rain comes and where the herds should be driven.”

His grandfather, too, had still dreamed. But since the whites were in Africa, he said, no one had dreams any more. Dreams were no longer needed because now the English knew every-thing.

His reply showed me that the medicine man had lost his raison d’étre. The divine voice which counseled the tribe was no longer needed because “the English know better.”

Far from being an imposing personality, our laibon was only a somewhat tearful old gentleman.

Jung closes with these lines: “He was the living embodiment of the spreading disintegration of an undermined, outmoded, unrestorable world.” a

In chapter 13 of Sapir’s Navaho Texts, titled “The Origin of Horses,” narrated by Cháálatsoh, we witness this same force of nature slain, gutted, fileted, and flash-frozen in space-time—as “anthropology” or “literature.”[33] (Just like what happens to “the little walker” when rendered into “fox” by a kind of linguistic taxidermy: it turns into “game” or “zoology.”) For the two planes don’t commute into one another; there is no intercourse between them, at least not in this manner. They are two different states of reality. Cháálatsoh could get away with it because he knew that the wave function of Equus (I shall call it) had collapsed. After all, what’s left when hózhó collapses? On the other hand, Cháálatsoh’s prayer to the Holy Ones suggests a yearning that, perhaps, it was not altogether ended. Such was the old man’s dilemma.

For Sapir to come to terms with Equus, he would have had to become part of the process, that is, be devoured by the quantum potential—where in fact there are no horses. [See Plotinus]

In fact we can go as far as to question whether this process should strictly be called a measurement, since here measurement in general no longer reveals what is there before the measurement interaction is switched on. Perhaps we should merely refer to it as an experiment, as Bell has suggested, or even a participatory experiment, or better still a participatory experiment revealing the potentialities of the system under consideration.[34]

The rules are inflexible and unforgiving: nonseparability, participation, and nonlocality. Yielding oneself to the process is not to be taken lightly. Sapir would have had to plunge into the vertiginous physics of the Big Bang, the origin, which is always here, always enfolding and unfolding, where time and space and their corollaries of measurement, prediction, and control are meaningless, where only the gift prevails.

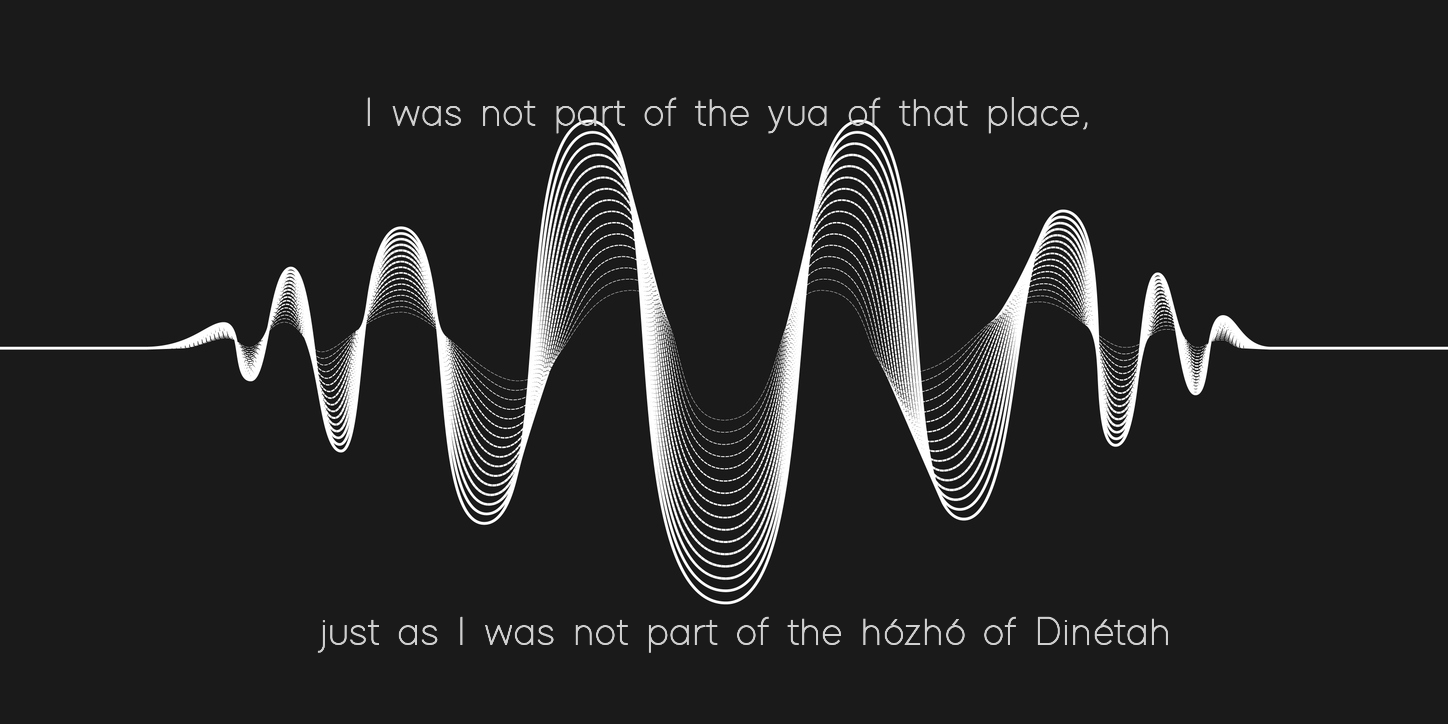

Yup’ik Eskimos repeatedly told me this in their own polite yet emphatic way. When I pressed them further, they ended the conversation by telling me to join them in the great dance (as Kalahari Bushmen call it) in wilderness, where the wild things are—where a man could jubilantly sing and drum, “Because he who comes [referring to the gift of caribou seen approaching in a dream] looks so fine!,” as a Naskapi exclaimed to Frank Speck.[35] This, I knew, I was not fit to do, since I have no relationship with tuntuvak, the Dark One, and the other wild things. I was not part of the yua of that place, just as I was not part of the hózhó of Dinétah.

I could learn the Yup’ik language as a linguistic exercise, as did my wife, and as Bringhurst and Sapir did with Navajo. I could listen to stories, as I did with Maxie Altsik and Sapir did with Cháálatsoh. But I could not be possessed by hózhó or yua.

This is why I returned to the landscape that molded me, where these lectures begin. Like Yeats returning to Innisfree and Dylan Thomas to Fern Hill, I returned to the place where anthropology ends.

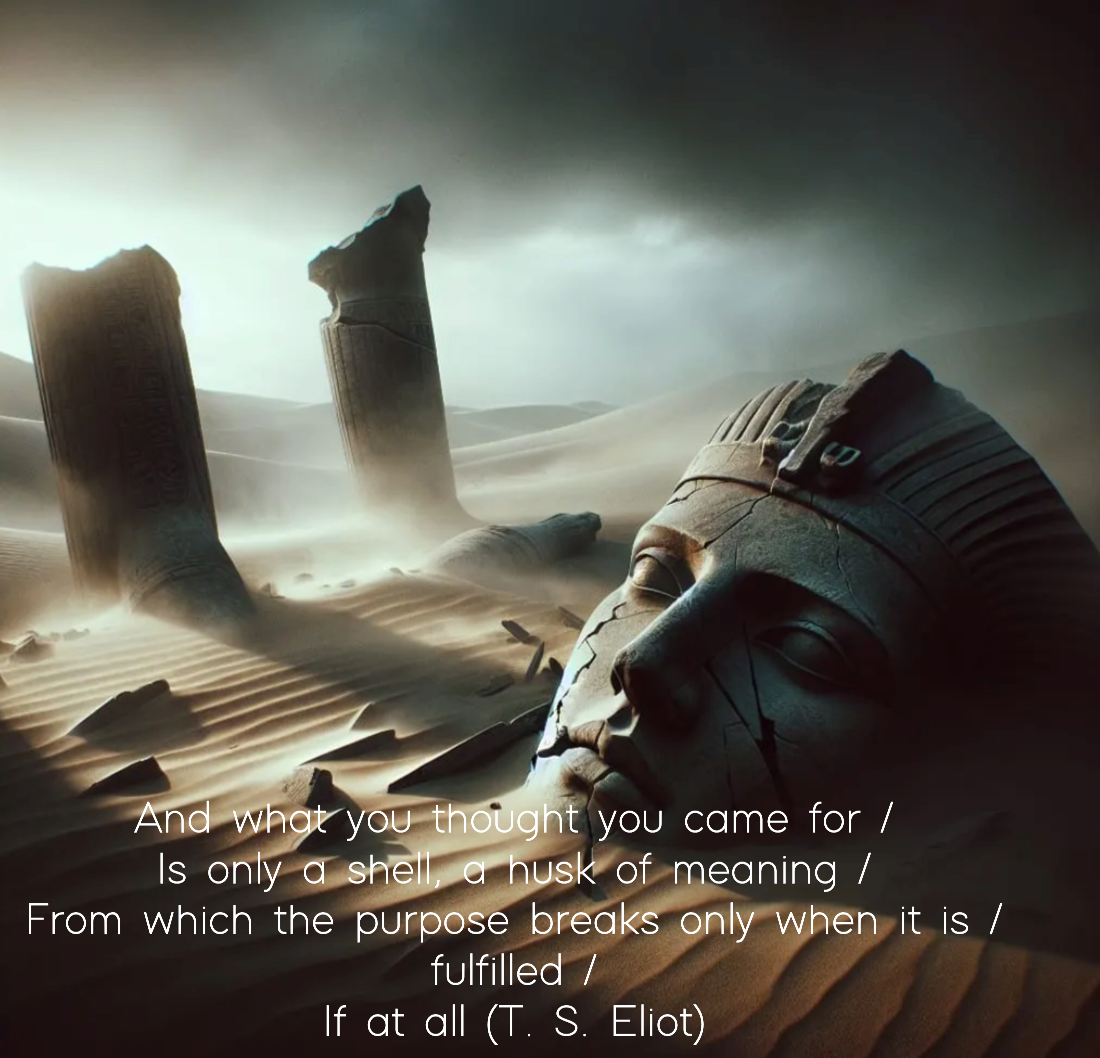

Would that I could inscribe Eliot’s lines on the pedestal of anthropology’s colossal wreckage, in the manner of Shelley on the shattered monument to Ozymandias, King of Kings:

And what you thought you came for

Is only a shell, a husk of meaning

From which the purpose breaks only when it is fulfilled

If at all.[36]

____________________

[19] Navajos speak notably softly. I speak from experience.

[20] Sapir, Navaho Texts, 127.

[21] Pronounced “hon-jho.”

[22] See John 1:1–4 (KJV).

[23] Dmitriy Zoxjkie Neezzhoni, “Diné Education from a Hózhó Perspective” (master’s thesis, Arizona State University, 2010), 16.

[24] The following section is quoted from Martin, In the Spirit of the Earth, 23–28.

[25] Sapir, Navaho Texts, 127.

[26] See Lecture 5, where I talk about Maxie Altsik.

[27] Personal communication.

[28] Sapir, Navaho Texts, 399–401.

[29] Bringhurst, Everywhere Being Is Dancing, 292, note 2.

[30] Calvin Martin, Keepers of the Game: Indian-Animal Relationships and the Fur Trade (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1978), 155.

[31] Speck, Naskapi, 177.

[32] Martin, Keepers of the Game, 155.

[33] Sapir, Navaho Texts, 109–27.

[34] Hiley, “Conceptual Structure,” 9.

[35] Speck, Naskapi, 92, 184–85:

An interesting example of a song dedicated to the caribou, and at the same time a very old one, was sung for me [in 1925] by Alexandre Mackenzie, nephew of the chief of the Michikamau band. He had learned it from his grandfather, who in turn had acquired it from his father, old Jérôme Antoine.

uca’m kabe’tc mino’nagonǝwa’

“Because of him who comes, it looks fine.”

The reference to “him” is to the caribou, the coming of which is a vision of joy in the dream of the hunter. The melody was most complicated and wild.

[36] Eliot, “Little Gidding,” in Four Quartets, 50.

- Jung, Memories, Dreams, Reflections, p. 265.[↩]