Dinétah

and the

Folding Chair Inequality

Part 1

Calvin Luther Martin, PhD

November 3, 2024

Sanskrit text carved into stone wall.

Here, “mind and matter appear as different aspects of the same underlying process

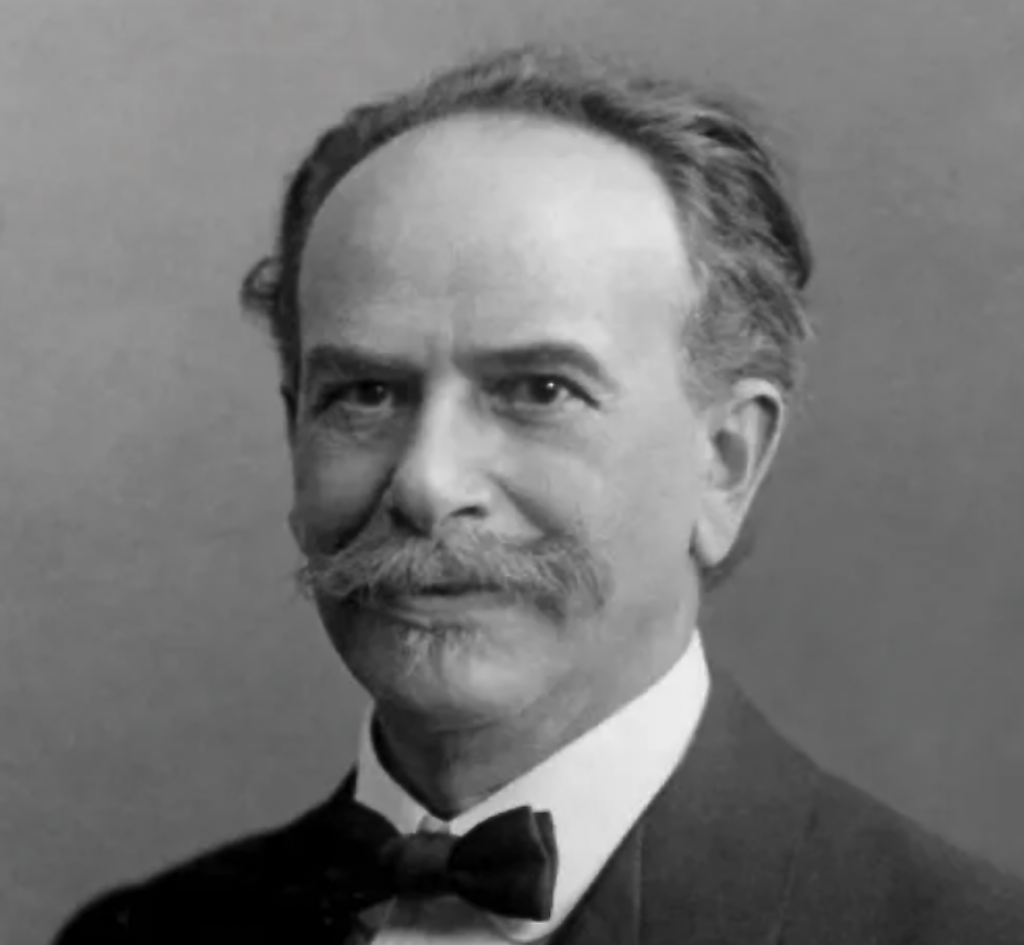

Professor Edward Sapir

Professor Franz Boas

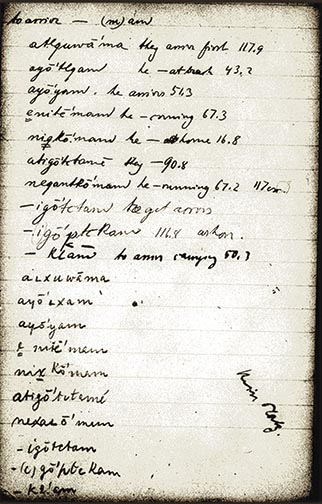

A page from one of Boas’s field notebooks.

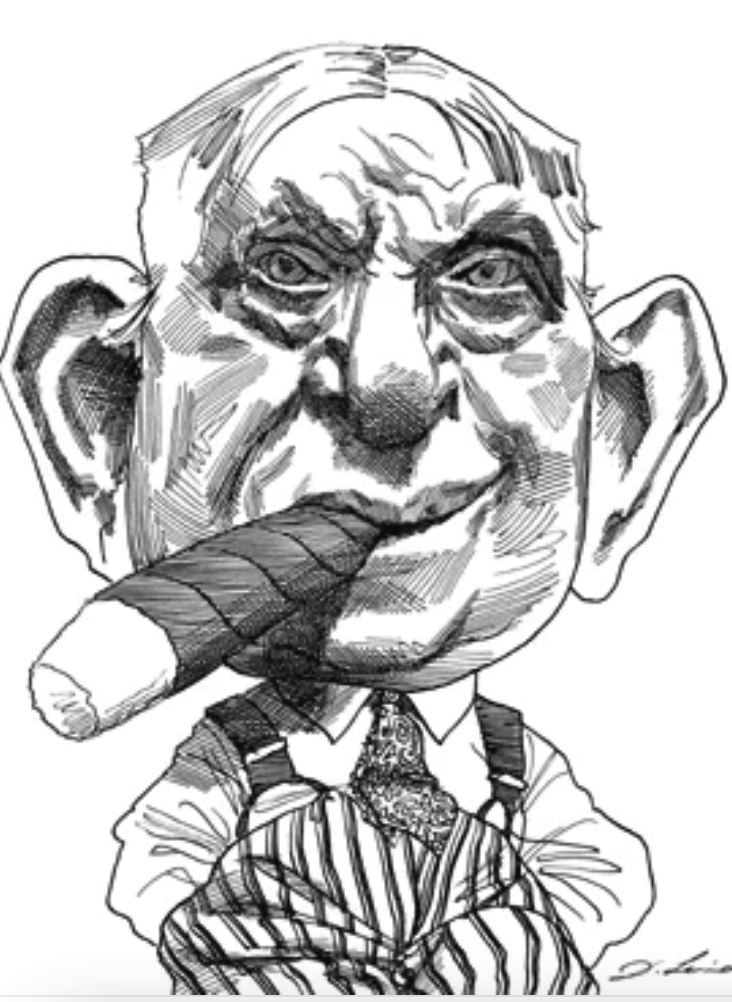

Henry L. Mencken

(David Levine)

The “senseless, stupefying stories” Boas found himself listening to.

“We are not bystanders.” Come with me to Dinétah, the land of the Navajo, to experience this.

I didn’t say you would understand what I said. I, myself, don’t understand it. It is beyond comprehension, just as the quantum potential is untouchable, impenetrable, and impalpable. I merely said you will experience it. (My wife and I lived for the better part of a summer in this strange landscape, where Nina was a physician at Sage Memorial Hospital in Ganado and at the Shiprock Indian Health Service hospital.)

The best place to begin is by standing on the rim of Canyon de Chelly (pronounced “de Shay”) and letting the wind and sheer air possess you. Begin thinking in the thought of the wind. “Only the wind / Seemed large and loud and high and strong,” writes Stevens.

And as he thought within the thought

Of the wind, not knowing that that thought

Was not his thought, nor anyone’s,

The appropriate image of himself,

So formed, became himself and he breathed

The breath of another nature as his own. [1]

Breathe the breath of another nature as your own. You are now ready to hear what I have to say.

Wind, say the Diné, is a Holy One. It exists beautifully, they say, originating long before the world came to pass. It is the source of life, breath, movement, thought, and speech. It animates earth, heavens, animals, plants, and humankind. Wind “is listening. We who are Navajo live here by means of it. From here we talk to it. If we plead with it, it hears us. From then on it is good.”[2]

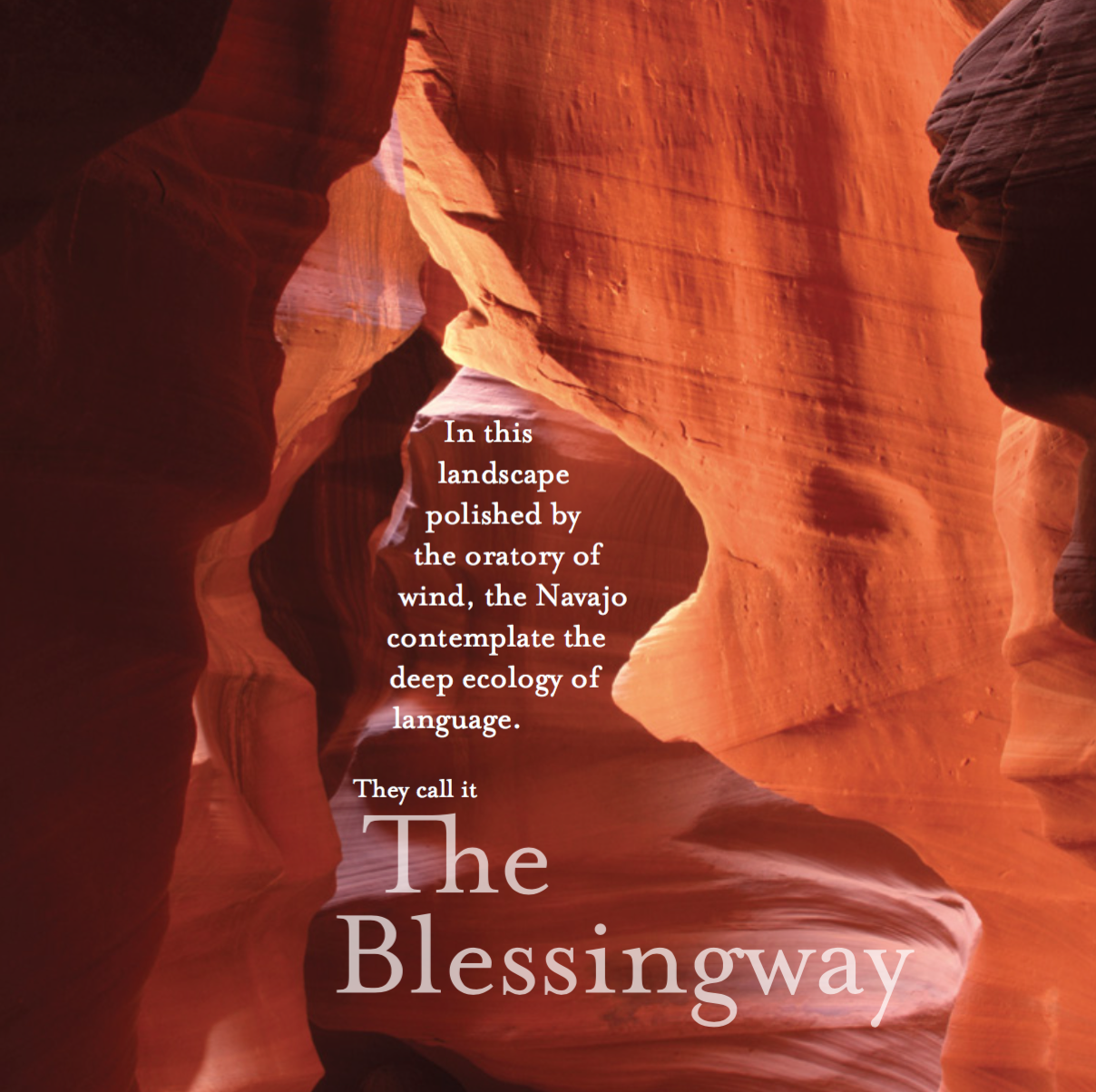

In this landscape shaped and polished by the oratory of wind, the Navajo contemplate the deep ecology of language. They call it the Blessing Way and Beauty Way.

They say humans are descended from the copulation of intersecting mist, when the female power of speech (bik’eh hózhó) “slid open like thighs warmed and wakened”[3] and clasped the male energy of thought (są’ah naagháii) to create są’ah naagháii bik’eh hózhó—the phrase that bore First Man and First Woman. The phrase is alive. Like breathing. “Because of the circle of completion, fulfilled in old age and death,” whispers the uncanny whirlwind, “there is beauty all around me.”[4]

Four words hold the Navajo universe together. Not, as in Western thought, four impersonal forces: gravity, electromagnetism, the strong force, and the weak force. Language for the Diné is a force of nature. “In the Navajo view of the world,” explains Gary Witherspoon, “language is not a mirror of reality; reality is a mirror of language. The language of Navajo ritual is performative, not descriptive. Ritual language does not describe how things are; it determines how they will be. Ritual language is not impotent; it is powerful. It commands, compels, organizes, transforms, and restores. It disperses evil, reverses disorder, neutralizes pain, overcomes fear, eliminates illness, relieves anxiety, and restores order, health, and well-being.”[5]

Interestingly, the celebrated Sanskrit philosopher of grammar, Bhartrhari (5th century AD), discussed and understood language in remarkably similar terms. As in, “The Supreme Word principle, or the Sabdabrahman, is the source, the sustenance and the end of all manifestation” a; “It is the word which became the worlds; the word became all that is immortal and mortal. It is the word which enjoys, which speaks in many ways. There is nothing beyond the word” b; “The ultimate reality from which everything comes is in the nature of the word” c

Language is a fundamental operator in the physics of Dinétah, part of its Globe of Thought. From the enfolding and unfolding of są’ah naagháii bik’eh hózhó comes the discourse that defines the arc of life for the land and all that dwell therein, including this canyon whose breath you and I now breathe as our own. There are no Cartesian subject-object boundaries, no res cogitans and res extensa, on this rim. Here, “mind and matter appear as different aspects of the same underlying process.”[6]

None of this is unique to Dinétah. I suspect Jesus encountered this reality in the Judaean wilderness, as did Thoreau on Katahdin and Jung in Africa. Of the three, only Jesus learned its language. Thoreau and Jung, unwilling or unable to learn it, found the experience terrifying, as I did, here in this landscape—as I shall describe. As for Jesus, substitute the word grace for beauty in this Navajo prayer, and you’ve got the Gospel (Good News).

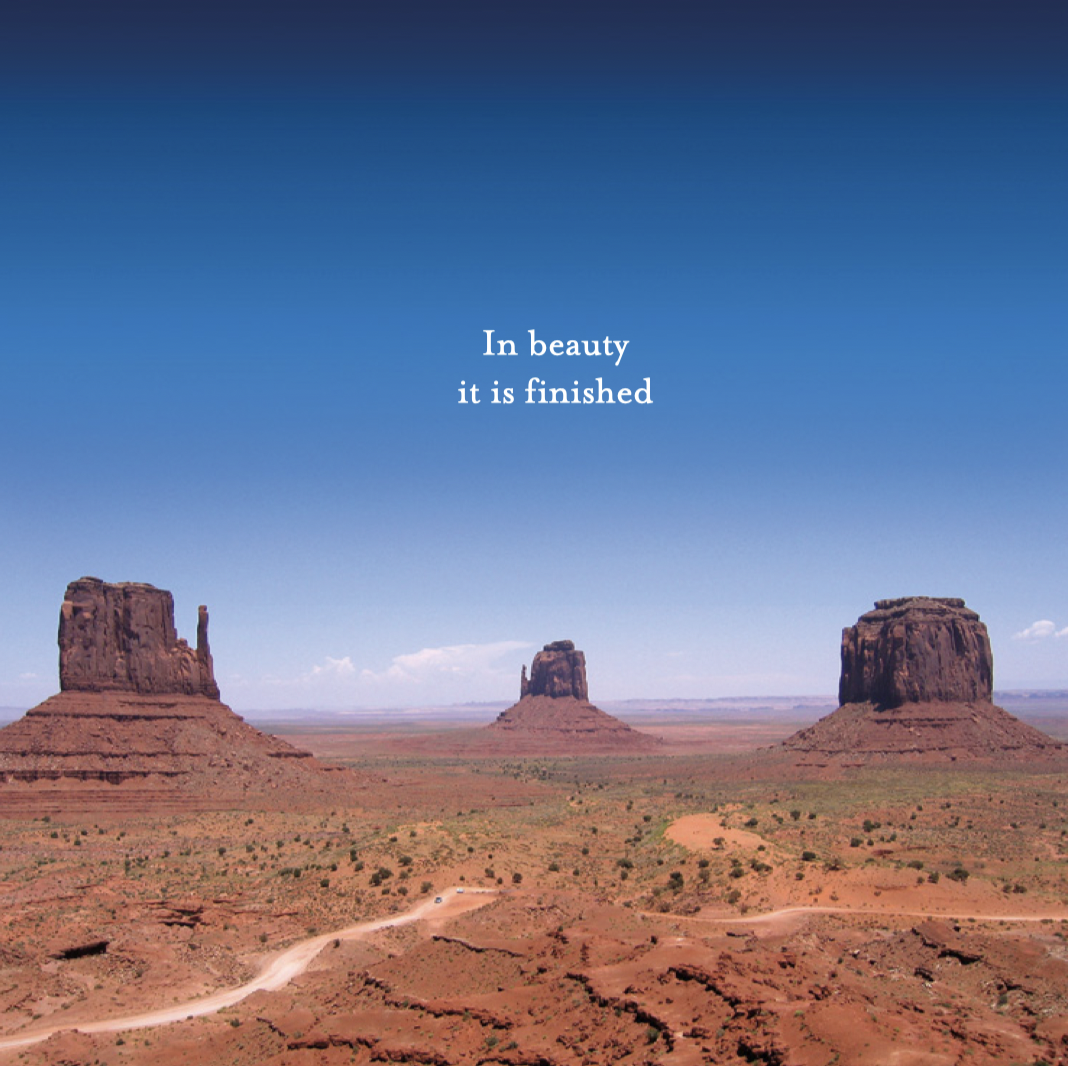

With beauty before me, I walk

With beauty behind me, I walk

With beauty above me, I walk

With beauty below me, I walk

From the east, beauty has been restored

From the south, beauty has been restored

From the west, beauty has been restored

From the north, beauty has been restored

From all around me, beauty has been restored[7]

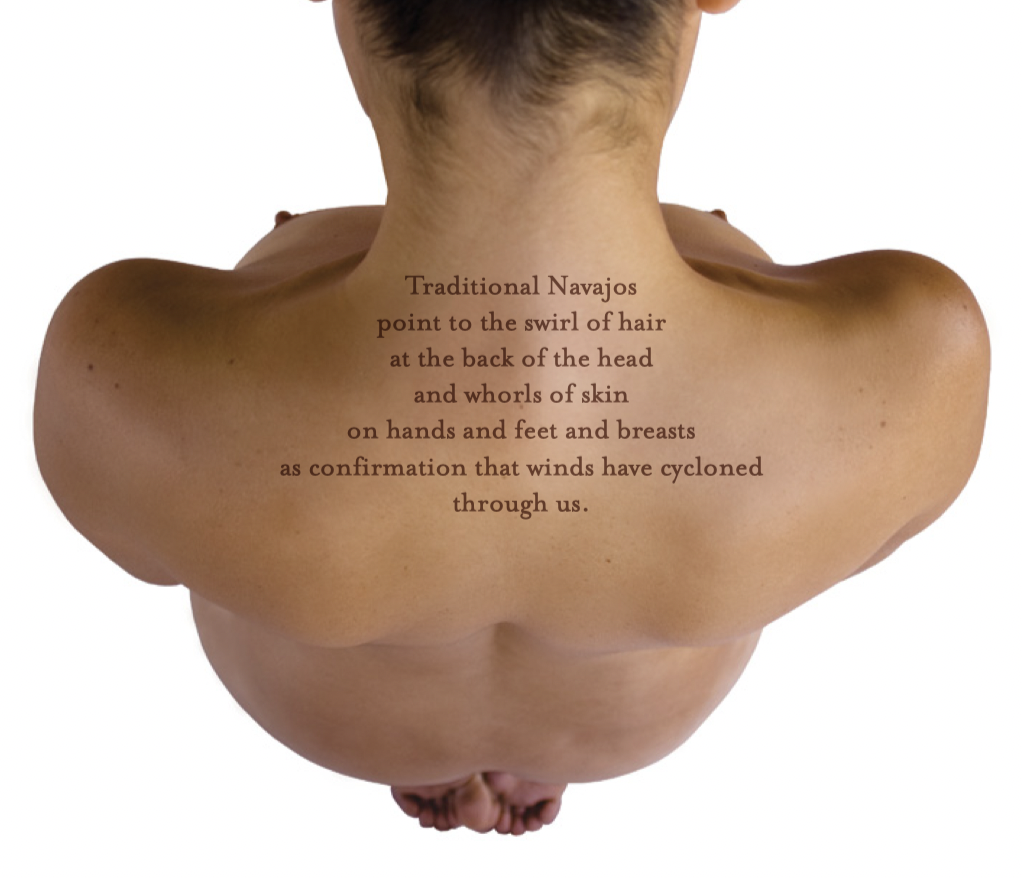

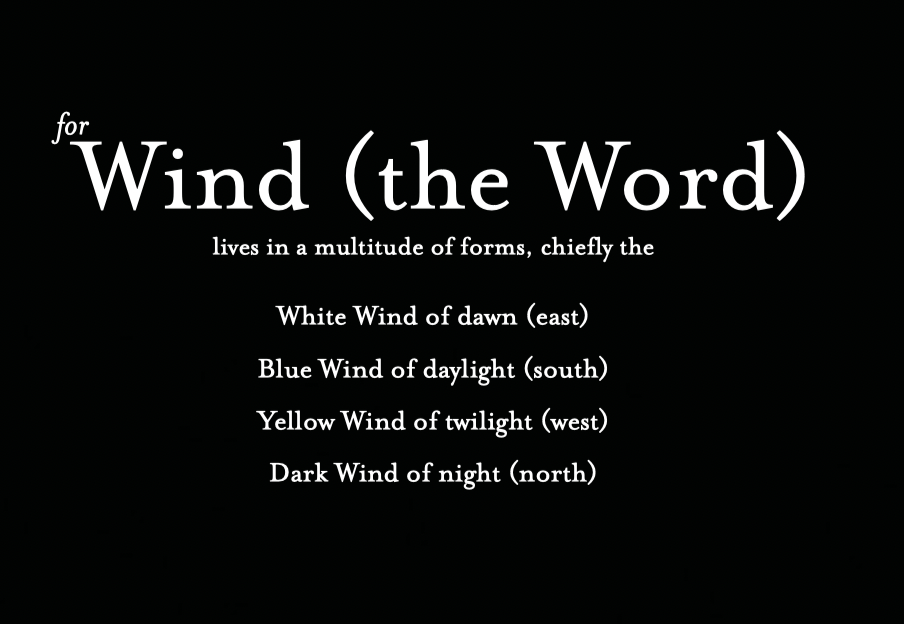

The Navajo point to the swirl of hair at the back of the head and whorls of skin on hands and feet and nipples as confirmation that cyclonic winds have blown through us. For Wind (the Word) lives in a multitude of forms, chiefly the White Wind of dawn (east), the Blue Wind of daylight (south), the Yellow Wind of twilight (west), and the Dark Wind of the night (north).

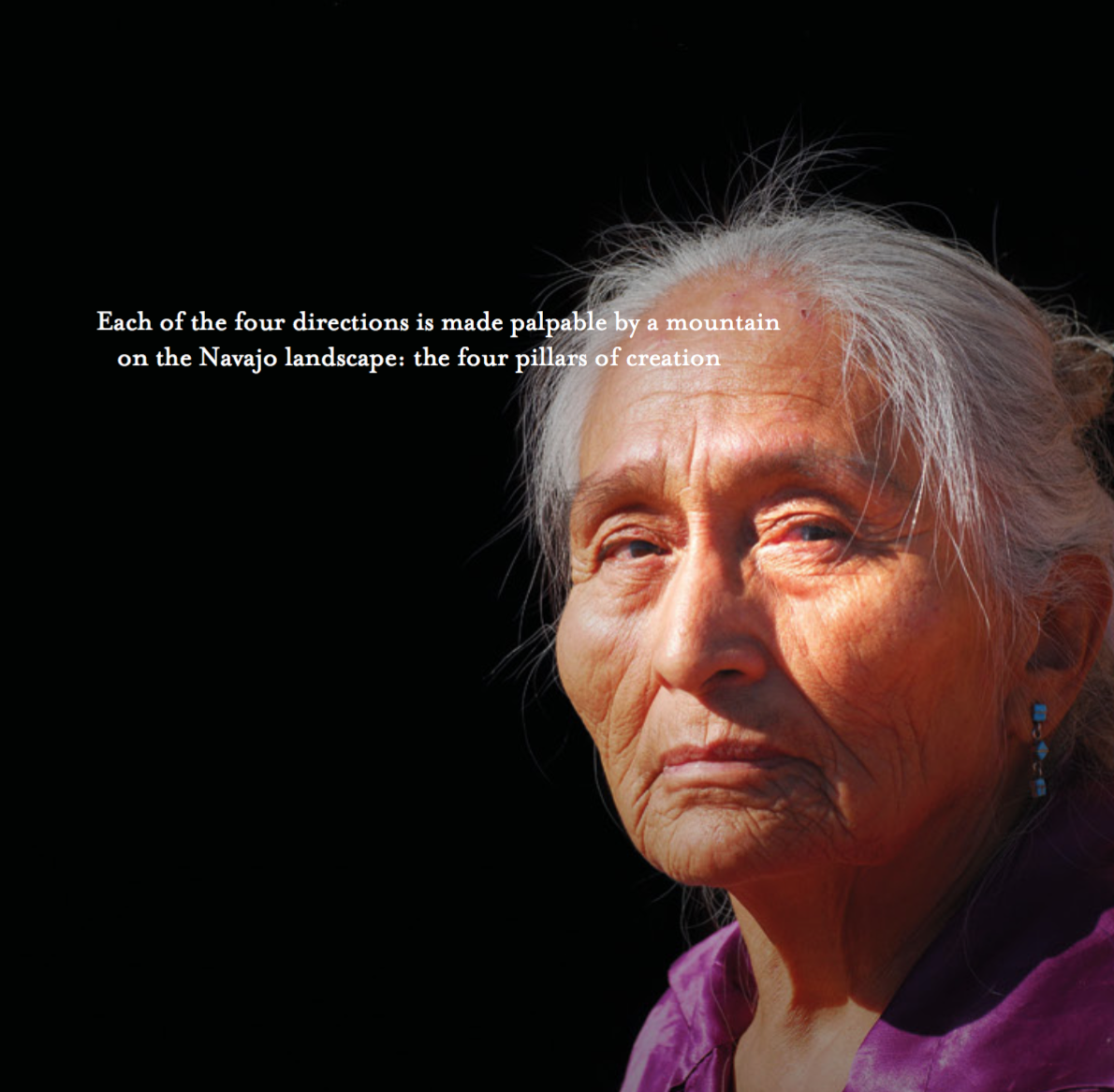

Each of the four directions is made palpable by a mountain on the Navajo landscape: the four pillars of creation, home to the Talking Gods and Calling Gods, Holy Ones that move and think and speak by wind’s power, sending messenger winds (Wind’s Child or Little Wind) to whisper wise counsel in the folds of the ear.

When we die, są’ah naagháii bik’eh hózhó—the living, breathing discourse—has been fulfilled, and Wind leaves us (or flees through neglect or misuse).

In beauty it is finished.

In the summer of 1929, a man named Cháálatsoh was hired by the linguist Edward Sapir to reveal the underlying process, the implicate order, of Dinétah outlined above. Sapir didn’t realize that this was what he was asking for. As far as he was concerned, the old man was a serendipitous archive of “myths and tales” and “origin legends,” together with “ethnological narratives” and sundry information on “the life of the Navaho.”[8]

The problem is there are no such things as “myths and tales,” “origin legends,” and other “ethnological narratives” in Dinétah. Such free-floating, unmoored, portable artifacts of “oral literature” or “anthropology” exist only in the uncoupled physics, the Island of Language of Western thought, uncoupled from the energy and momentum manifold of places like Dinétah. I will come back to this.

As it happens, myths, legends, and tales were not Sapir’s chief interest. “Dr. Sapir’s main objective,” we learn in the introduction to Sapir’s field notes, “was the study of the Navajo language, and the data presented in the following pages provide a necessary groundwork for such a study. Viewed in this light, the volume is of first importance, since little that has been published heretofore has had much value for linguistic research.”[9]

Behold the superman of science pushing back the frontiers of knowledge in something called linguistic research. (We will get to the “oral literature” canard in a moment.)

Sapir’s mentor at Columbia was Franz Boas, another man whose great advantage as an academic was that he was never burdened with an understanding of the people he was studying. The following is from one of Boas’s letters written soon after his arrival on Vancouver Island, where he promptly began interrogating any Indian, male or female, he could buttonhole and dazzle with cash. It’s worth pondering these passages to appreciate the mentality of the man hailed as the father of American anthropology. This is the man who trained the first generation of American ethnologists, including Ursula Le Guin’s father, Alfred Kroeber.

September 24, 1886: We have had rain since the day before yesterday; this does not improve my stay here. I am cross because my Tsimsian has deserted me, and so far he has been the best one I have had. From experience I should know that such things happen, but it is easier said than done not to be angry about it. I told the good man, who, by the way, is one of the most religious, that he was the greatest liar I had ever known since he did not keep his word. I told him I would tell his pastor about it. I immediately went in search of another and hope I shall be successful tomorrow.

I must now relate what I have done since yesterday. In the morning my Tsimsian, Mathew, the one who disappointed me today, was here. For six hours he told me a long story which I of course copied. I had hoped to obtain it in Tsimsian, but now I shall be unable to do so. The stories are in part completely senseless, and I became quite stupefied. Basically, however, they contain so many interesting religious and social facts that I want to hear them.

. . . I hope I shall find another good Tsimsian tomorrow to replace Mathew, whom I cannot curse enough. He was able to dictate very well. It reminds me so vividly of the Eskimo—they also ran away in the middle of a tale.[10]

September 25: Today was the worst day since I have been here. I learned practically nothing because I spent the entire day running about in search of new people. This morning I looked for some Tsimsians who live in another part of the city [Victoria, British Columbia]. After a long search I finally found them but could get nothing from them. All I got was a few notes about their family lines and the patterns of their clothing. A woman started to tell me the story of the thunderbird, but she did not get very far. She claimed to have forgotten the most important part.[11]

Then this, from a letter to “My dear Wife,” October 27, 1894:

My Tsetsaut is quite exasperating. I get some words and legends, as well as a few interesting notes on customs, but the language! The following example will explain my difficulties. I ask him through my interpreter, “How do you say in Tsetsaut: ‘If you don’t come, the bear will run away’?” I could not get him to translate this. He would only say, “The Nass could be asked a thing like this; we Tsetsaut are always there when a bear is to be killed. That’s why we can’t say a thing like this.” I also asked him, “What is the name of the cave of the porcupine?” His answer was only, “A white man could not find it anyway and therefore I don’t have to tell you.” Thus it goes all the time, and you can imagine how slowly I progress.[12]

Finally this, from a letter to his children from Fort Rupert, December 1930:

Yesterday there was quite a mess. The chief, who is hated by everyone, gave a great feast. A cow was bought and butchered, and the meat distributed. There were speeches, and he made his adopted grandchild the heir of his son. And then around the brat, a real good-for-nothing, copper plates were placed which were to prevent anybody from saying anything against him. A copper plate was placed above his head, which meant that he breaks it to show his greatness. A speech was given while the meat was distributed. He [the chief] said, “This bowl in the shape of a bear (is) for you, and you, and so on; for each group a bowl.” The bowls, however, are no longer here. They are in the museums in New York and Berlin. Only the speech is still the same. In the same way a child was supposed to be named, and they said [text missing], but these are only words. It is strange how these people cling to the form though the content is almost gone. But this still makes them happy.[13]

I recall Mencken’s assessment of William Jennings Bryan: “Ignorant, bigoted, self-seeking, blatant and dishonest.”[14] To which one might add of Boas: “ruthless.” Boas’s character defects are minor compared to his disastrous ontological problem. The man had absolutely no grasp of the implicate order that was crashing, literally before his eyes, in the non-space-time manifold he had intruded upon.

American anthropology was not off to a promising start.

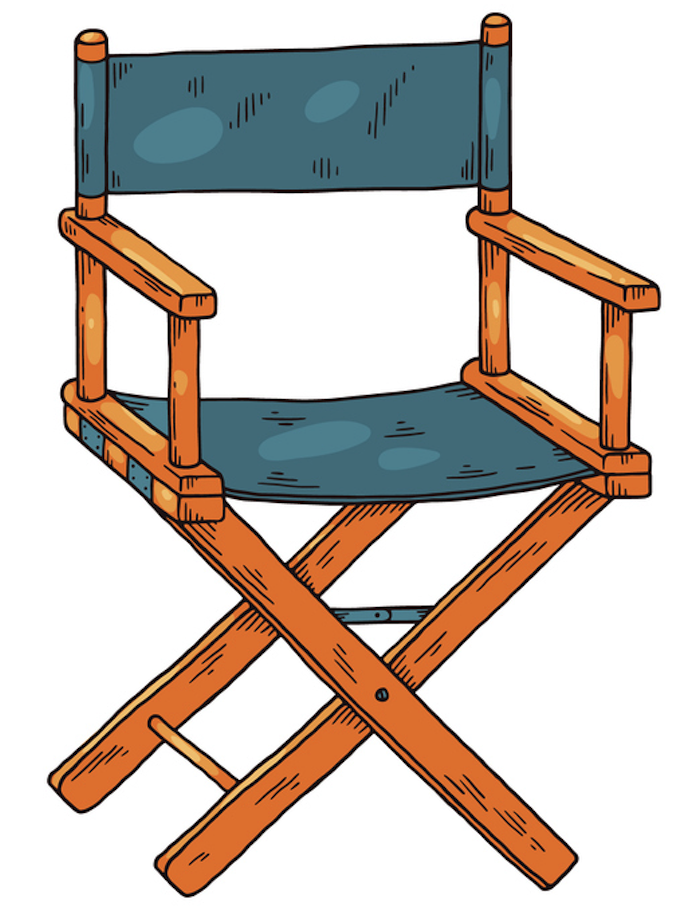

In 2008 the Canadian poet Robert Bringhurst revisited Sapir’s Navajo myths and deployed the same fallacy Sapir utilized and Boas pioneered. I call it the Folding Chair Inequality. I alluded to it several paragraphs ago. There are no phenomena that can be (a) uncoupled from the energy-momentum manifold of places like Haida Gwaii or Dinétah, (b) packed or written up and shipped elsewhere, and (c) whipped out like a folding chair, all the while unaffected by the process. This applies to things we call physical artifacts (such as bear-shaped bowls) and oral literature (such as myths).

The assumption that no change has occurred is a fallacy. And yet upon it we have built the whole academic enterprise and, indeed, civilization. It can be generalized as follows:

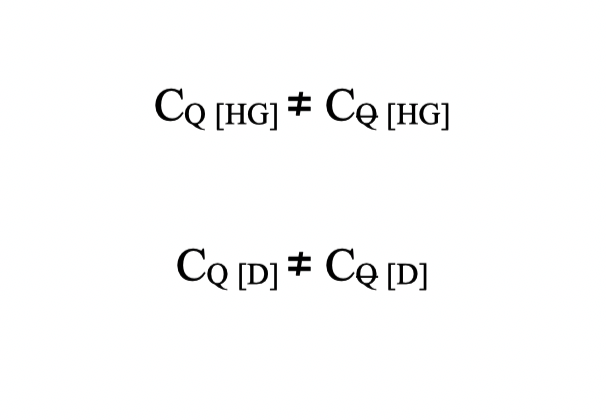

The Folding Chair Inequality

A folding chair (C) originating in the implicate order (Q)—hence CQ—of, say, Haida Gwaii (CQ [HG]) or Dinétah (CQ [D]), is not the same folding chair once it is removed from QHG or QD and deployed outside its implicate order (Q). Note that the only change that has occurred in the equations below is that Q has collapsed into Q. The collapse is fundamental. The chair is no longer the same chair, despite what we think.

CQ [HG] ≠ CQ [HG]

CQ [D] ≠ CQ [D]

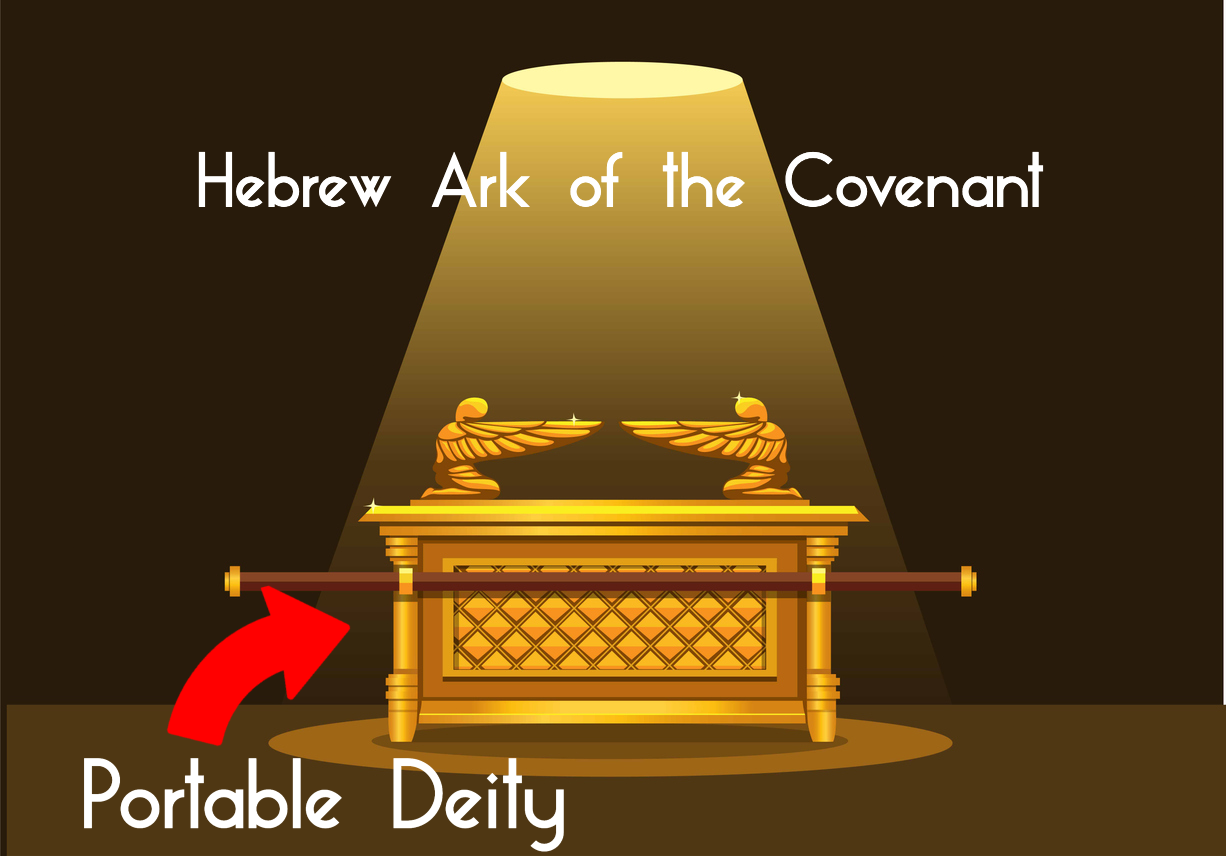

The fallacy has a long history, probably originating with the Hebrews when they packed their deity into a box and set out to conquer as much of the Levant as they could.[15] (The idea being that Jehovah-in-the-Box could take dominion over every landscape where he was parked. Christians perfected the strategy via the Bible, the ultimate eminent domain device, which allowed them to magically take dominion over every heathen land where God’s Word was carried. This, of course, was the purpose of the Moravian seminary where I taught in Alaska.)

What I said about Boas and the bear-shaped bowls applies, of course, to the “senseless, stupefying stories” he collected for the greater glory of ethnography. His student Sapir did the same, relocating performative language from Dinétah to the pages of the Linguistic Society of America, where, of course, it was dead on arrival.

Robert Bringhurst repeats the Folding Chair Inequality. Calling Sapir “the prince of linguists,” Bringhurst thanks him, along with Pliny Earle Goddard and Gladys Reichard, for making the “brief golden age of Navajo [oral] literature” come to pass. Translators like Sapir, he enthuses, “open the door to a voice from somewhere else, and they create meaningful work for readers or listeners, by giving them a route that they can travel, a bridge that they can cross, partway into another linguistic experience. Good translations are never complete. You must meet them partway. You must translate yourself.”[16]

Forget about opening a door or crossing a bridge. There is no door, no bridge, no “other linguistic experience.” There is only Dinétah, where “language is not a mirror of reality; reality is a mirror of language.”[17] Forget about translating yourself; according to Witherspoon’s axiom—“reality mirrors language”—it’s not possible. “Mind and matter,” Hiley reminds us, “appear as different aspects of the same underlying process,” the process of enfolding and unfolding in the energy-momentum manifold of Dinétah.[18] Language is part of this mind and matter.

What is possible, Mr. Bringhurst, is the risk of being transformed by Dinétah, Haida Gwaii, the Judaean Desert, Mount Katahdin, or, if you are Carl Jung, Africa. Yes, that’s a sobering thought.

____________________

Footnotes

[1] Stevens, “The Constant Disquisition of the Wind: Two Illustrations That the World Is What You Make of It,” in Collected Poems, 542.

[2] James Kale McNeley, Holy Wind in Navaho Philosophy (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1981), 48.

[3] Rainer Maria Rilke, “The Temptation,” in New Poems: The Other Part, 1908, trans. Edward Snow (New York: North Point, 1987), 49.

[4] This is a loose translation of są’ah naagháii bik’eh hózhó, a highly sacred phrase in Navajo speech and cosmology, and so charged with significance that scholars and the Navajo often decline to translate it. See Gary Witherspoon, Language and Art in the Navajo Universe (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1977), 19–23; McNeley, Holy Wind, 16, 23, 52–55, 57.

[5] Witherspoon, Language and Art, 34, emphasis his.

[6] Hiley, “Non-Commutative Geometry,” 15.

[7] Witherspoon, Language and Art, 153–54.

[8] The phrases are taken from the table of contents of the volume Navaho Texts, subsequently published by the Linguistic Society of America (1942), bearing Sapir’s name. Edward Sapir, Navaho Texts, with Supplementary Texts by Harry Hoijer, ed. Harry Hoijer (Iowa City: University of Iowa / Linguistic Society of America, 1942).

[9] Sapir, Navaho Texts, 9.

[10] Franz Boas, The Ethnography of Franz Boas: Letters and Diaries of Franz Boas, Written on the Northwest Coast from 1886 to 1931, ed. Ronald P. Rohner, trans. Hedy Parker (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1969), 24–25.

[11] Boas, Ethnography of Franz Boas, 25.

[12] Boas, Ethnography of Franz Boas. The letter is dated October 27, whereas this passage is dated October 29. Evidently Boas added to the letter before it got picked up by the mail carrier.

[13] Boas, Ethnography of Franz Boas, 297, emphasis mine.

[14] Henry L. Mencken, “The Scopes Trial: Bryan,” Baltimore Evening Sun, July 27, 1925.

[15] See William Foxwell Albright, Yahweh and the Gods of Canaan: A Historical Analysis of Two Contrasting Faiths (New York: Doubleday, 1968), 168.

[16] Robert Bringhurst, Everywhere Being Is Dancing: Twenty Pieces of Thinking (Berkeley, CA: Counterpoint, 2008), 89, 285, 294–95.

[17] Witherspoon, Language and Art, 34, emphasis his.

[18] Hiley, “Non-Commutative Geometry,” 15.

~