Crackup !

Calvin Luther Martin, PhD

October 27, 2024

Dante

Rilke

Abraham sacrificing Isaac (Harold Copping)

Quahog shells with loon feathers (Nina Pierpont)

‘The words and consciousness that live in a shell”

Jehovah

e e cummings

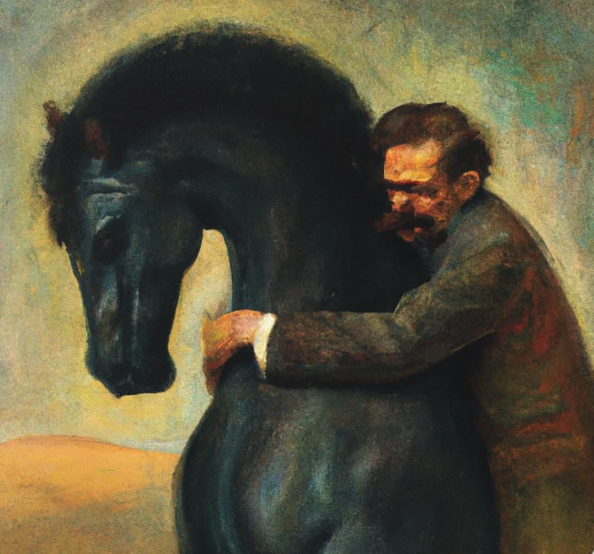

Chauvet, Equus

Richard Wagner

Nietzsche

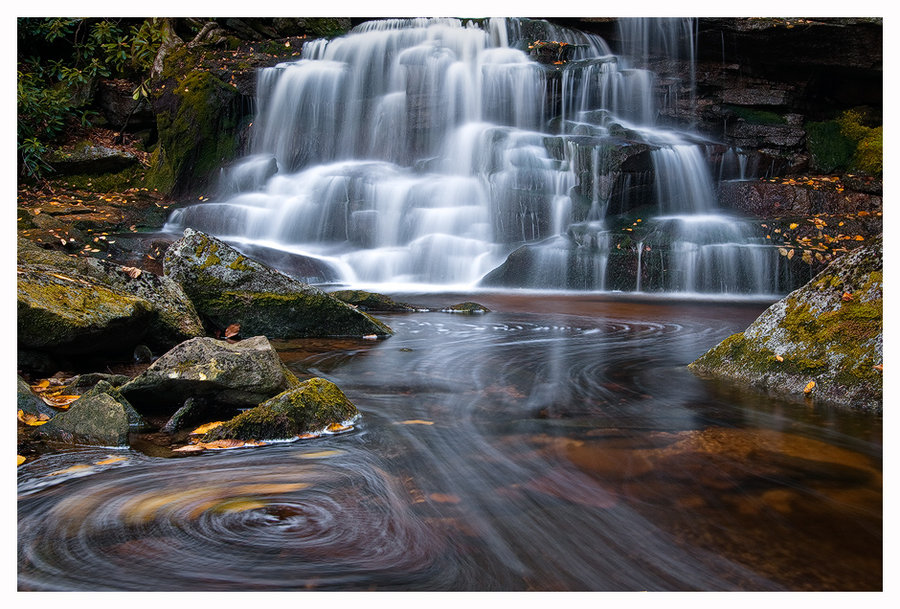

Black night, except there on the northern horizon, low: faint white light gathers itself. Constellations wheel slowly. The Pleiades dance in the east. Seven: I count them.

The light grows, glows brighter, silent fingers arching across the sky to the dome of heaven. Then—ripples. Huge cosmic ripples. “Now it still ripples, now it still murmurs, ripples, it still sighs, still hums.”[1]

The aurora comes alive, flowing into the vault of heaven, sending long jets, volleys of light. Rippling, discharging, immense. White, green, some red. Half the night a shimmering tissue of light—streams of cosmic matter.

All this above this mountain pond this autumn night. Loons call, another rippling. Barred owls growl and scream, resonating strangely through spruce forests.

Was it this way at the beginning of creation? The Maya say it was. The wise men, they say, remembered and wrote it down. “Whatever might be is simply not there: only murmurs, ripples, in the dark, in the night.”[2]

This autumn night I witness creation. This autumn night I shall die.

It is the dark just before dawn. The woods are quiet and still. Nina sleeps nearby; I hear her rhythmic breathing.

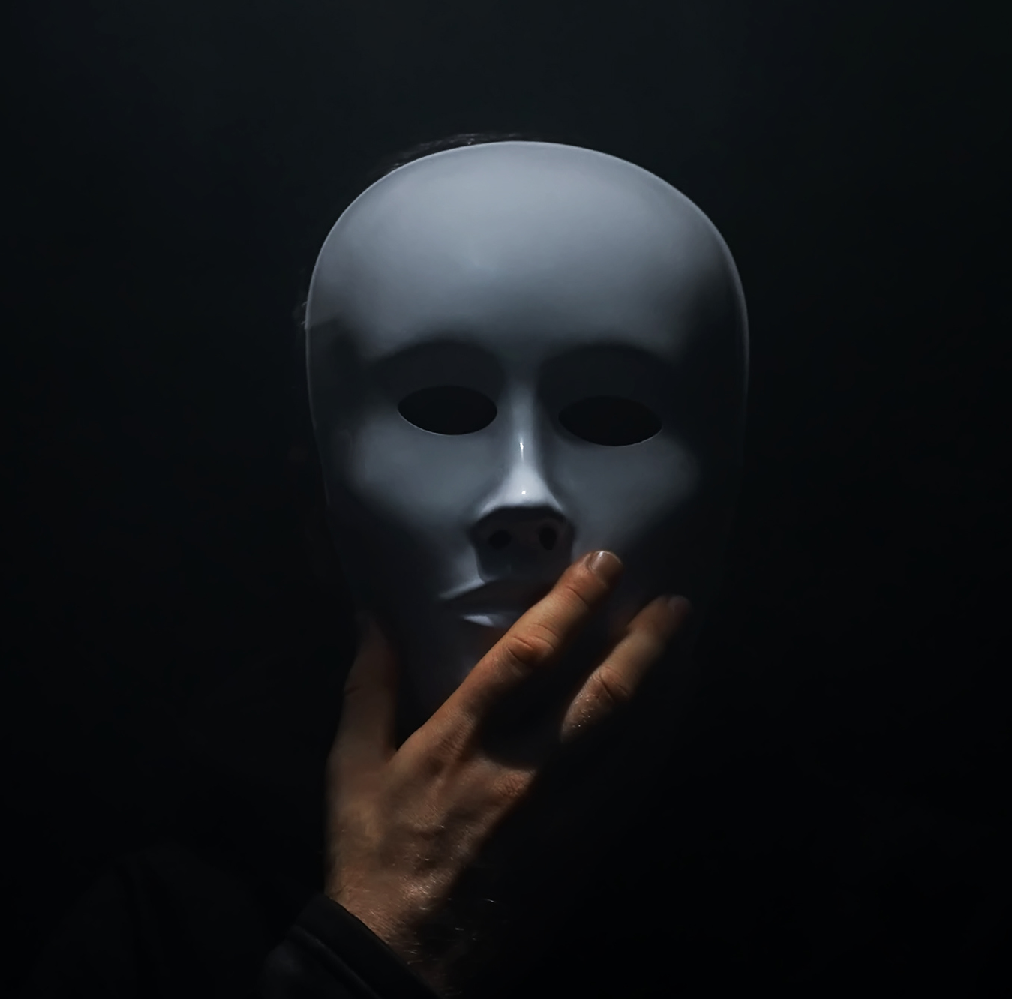

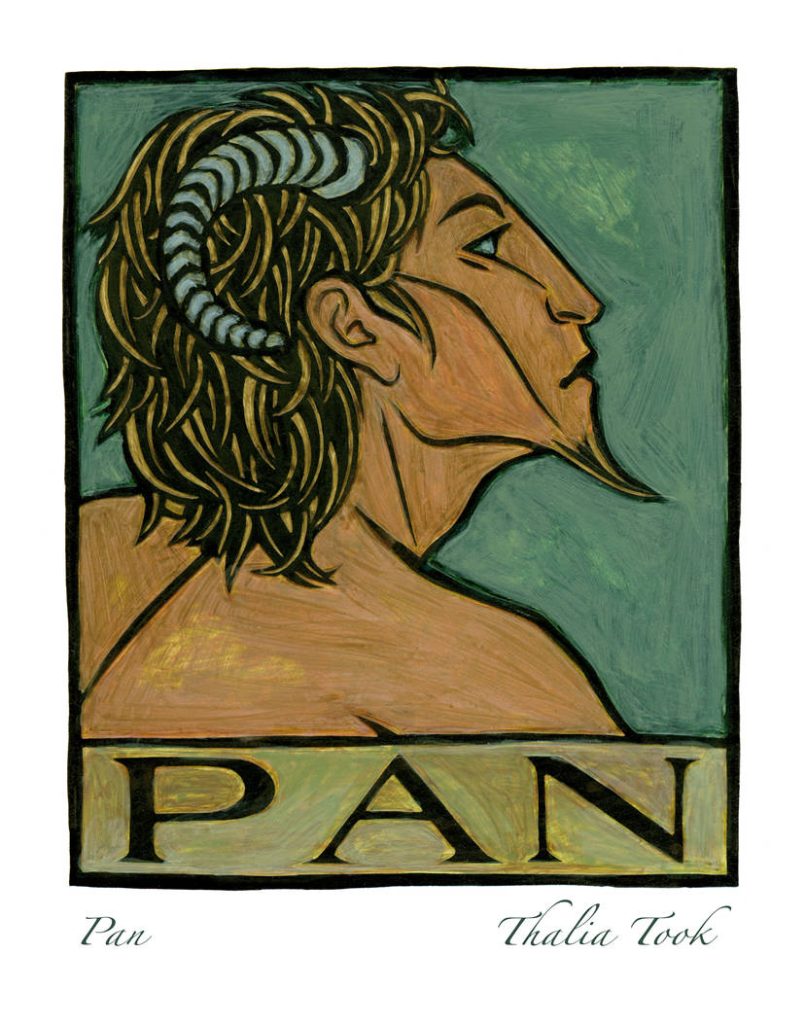

Something awakens me. The messenger, in the strong time when the old gods walk again among mortals, the piper at the gates of dawn:[3] is it he who summons me awake, then snatches away my hearing? A roaring like wind in my right ear, and sound vanishes. Just like that. Only a god would do that.

I shout for Nina to wake up. She’s groggy, trying to follow what I’m saying. I squint at the sky and trees above me as everything begins to spin. Left to right, the universe scrolls past. I close my eyes. The vertigo continues beneath my eyelids. “Nina, everything is spinning!” She gently urges me to go back to sleep. I’m getting nauseous.

Terrified by what’s happening, I peel off my sleeping bag and stand up, but I can’t keep my balance. I tell Nina I can’t stand, that I’m about to vomit. I feel her grasp my arm, steadying me. No, I can’t walk to the car: I have no balance. She throws my arm over her shoulder and virtually carries me.

While she goes back to gather our gear, I lean out the door and vomit. The moon’s brightness hurts my eyes.

I black out.

This is how it begins, my encounter with Something that will lead me by the hand through the valley of the shadow of death.[4] Or is it the spirit of Hiawatha, taking me where he went in his rage and grief? Over the next six months I too will become a woodland wanderer, splitting the sky with grief, wishing to die, barely able to eat or sleep, cloaked in darkness and filled with vague yet vivid fear.

To write of the experience is painful. “Ah, how hard it is to tell / the nature of that wood, savage, dense and harsh,” wrote Dante of his own dark woods;

the very thought of it renews my fear!

It is so bitter death is hardly more so.

But to set forth the good I found

I will recount the other things I saw.[5]

I was in a realm of tremendous power that seemingly controlled me, in the grip of the universe insofar as mortal man can experience this. I was neither truly dead nor truly alive. I was utterly vulnerable. Something had sliced me open with a filleting knife and bared my soul to the gaze of any passing man or woman. I was a spectacle.

Only one power remained to me: the power to denounce this, or assent to it. Denunciation, I somehow knew, would mean annihilation. Assent, though counterintuitive, would lead me out of the darkness and back to the conversation of mankind.

I chose assent. I would not call this faith, for I had no faith in any particular outcome. That, after all, is the insidious gyre of depression. I only knew that I was captive to some vast, incalculable strength, and that whether I lived or died, this mighty thing would continue to enfold me, if not crush me. This was surrender, not faith; the difference is consequential. Very slowly I began to learn my first lesson: faith is not something I create. Faith is created within me, reinventing me even as it is given form.

Whoever was beaten by this Angel,

(who often simply declined the fight),

went away proud and strengthened

and great from that harsh hand,

that kneaded him as if to change his shape.

Winning does not tempt that man.

This is how he grows: by being defeated, decisively,

by constantly greater beings.[6]

Everything I cherished was on the line. I was painfully aware that the words of comfort and assurance I had spoken in lecture halls, written in books and letters, were springing back at me, seizing me by the throat, demanding meaning—the meaning of my life. I felt like the Old Testament patriarch Abraham, commanded by Jehovah to sacrifice his son Isaac. The Almighty had told Abraham and Sarah that Isaac would found a great nation, and then, in a seemingly terrible contradiction, instructed Abraham to slaughter this child. As the old man proceeded with his preparations, did it not occur to him that this was insane, that he, himself, had gone mad? Yet some force larger than himself had brought him to this awful state, devoid of human reason. Abraham surrendered; he had no faith in a particular outcome, that Jehovah would stay his hand before he plunged the knife. (We know the outcome only because we lived after the event.)

So I too saw my mind and spirit—the mind and spirit that I cherished more than life itself—bound and stretched on an altar, a sacrifice to something incomprehensible to me. Like Abraham, I knew I was in the presence of the Knower. Like Abraham, who realized in that awful moment that his beloved son was not his, I realized that my mind and spirit were not mine, after all.

Loons call, a rippling. Barred owls growl and scream, echoing strangely through spruce forests. Hiawatha knew he couldn’t heal himself; he knew that someone else would have to fathom his torment and utter words that literally carried the substance of healing.

By and by he came to a lake, as if summoned. There are mergansers and loons out there. He had met Peacemaker and embraced the gospel of peace; he had been released from his cannibalism; still, evil had attached itself to him once more. Yet he refused to speak its story. Mostly he was mute. Except by this lake, before these waterfowl, his heart finally spilled forth. With arms raised, he boomed out over the water: “You probably wonder why I am standing here before you!” It was all that he could say.

The birds gazed at him, and they saw horror. All at once they fled, flapping and slapping their wings, sprinting across the surface as loons do. Soon they lifted clear, and as they did, so say the myth tellers, they lifted the water with them, as one would lift a blanket from a bed.

The astonished man was left standing at the edge of an empty lake bed. Gingerly he stepped forward. Looking down, he noticed lovely purple-and-white shells glistening all about him. Stooping, he gathered a handful.

I make it a habit to carry one of these shells in my pocket: quahog (Mercenaria mercenaria), a large clam commonly found on the beaches of the Atlantic coast. Iroquois call it wampum. More accurately, it is the shell from which the cylindrical wampum beads are drilled. Whatever shell it was that Hiawatha found on the lake bed, the Iroquois have for centuries remembered it as quahog.

Hiawatha had the growing sense that there was something remarkable about the shells, that they were literally a different language, deriving from a different story. Absurd, we would say. A category error. A shell surely cannot have powers of speech, says the modern mind.

He strung the shells together and hung them on a stick. By now he was certain there was healing power within them, healing words that they could utter only through someone conversant in their language, someone who shared their consciousness. He yearned to hear the words locked within. Till then, he merely hung them wherever he was camped, hoping to meet someone who could release their words of requickening.

Faithfully carrying the mysterious shells, he wandered, eventually winding up in the Adirondack wilderness where I too have arrived, many years later, with my own shell in my pocket, and my own yearning to unlock its speech.

Preaching nearby among the Mohawk, Deganawidah sensed Hiawatha’s crisis, like the scent of a forest fire. He set off in search of him.

Finding his camp, Peacemaker concealed himself, meaning once again to take the measure of this troubled man.

Presently the fugitive began talking to himself. If he could, he said, he would grasp these shells and read them aloud. With that, the Peacemaker approached. Taking the distraught, astonished man by the hand, he gathered up the shells and began declaiming their words, their power, their genius.

Now then I say, I wipe away the falling tears so that peacefully you might look around. And then I think something stops up your ears. Now then with care have I removed this hindrance to your hearing; easily then it may be you will hear the words to be said. And also I think there is a blockage in your throat. Now therefore I also say I remove the obstruction so that freely you may speak in our mutual greetings.[7]

This speech is sacred among the Five Nations. They call it the Condolence and Requickening Ceremony. In former days, the words were nothing without the shells; wampum, they say, propped up the words. Hiawatha realized this. Peacemaker’s genius was that he could speak the words that live in a shell, words inherently healing, as if they were living, breathing Good News. Possessed by them, Hiawatha was reborn into clear-mindedness, as the Iroquois put it.

This is what I have come to find: the power of the incarnate word. Not metaphors, not symbols, not logic or persuasion—the Redeemer speaks none of these. He speaks the words, and consciousness, that live in a shell.

It has been a long journey. It’s taken many years to arrive at this shore in this darkness, to reach up and turn off the headlamp. To stand in the presence of a great silence that has waited for me through all the ages. To experience myself and this place spoken by the voice of loon, before whom I am inarticulate and uncomprehending.

Alas, no Redeemer materializes before me out of the darkness, just a vague sense of the tormented silent creature who preceded me centuries ago—Hiawatha, in whom humankind’s ancient fluency with the earth was rekindled here, in the womb of wildness.

“Time stirs with her slow spoon,” muses Mary Oliver.[8] Two years pass between the events described in the last lecture and this one, when the Redeemer makes itself known to me in the same wilderness—as I say, in the mythically charged time before dawn. What comes is no Christlike epiphany, like Hiawatha´s second encounter with Peacemaker and the revelation of the shells. No, what comes, as I say, is the terrifying angel of Rilke’s Duino Elegies, a nameless thing that will guide me through a living death, a journey I cannot decline.

“Give his light hands nothing to hold / of your burdens,” warns Rilke of this being;

otherwise they’ll come at night

to you, to test you with a fiercer grip,

and go like someone angry through your house

and seize you as if they’d created you

and break you out of your mold.[9]

This was not a night spent camping beside a benign Walden Pond. Like Thoreau descending Mount Katahdin, I felt myself seized by Chaos and Old Night. This was the maelstrom of the “unhandseled globe.”[10]

What does one make of Chaos when it is no longer an abstraction, res extensa, but suddenly becomes real and possesses and devours us?

Thoreau borrowed the phrase “Chaos and Old Night” from Paradise Lost, the epic that brought me to tears of recognition when I read it as an adult. I was raised a seventeenth-century Puritan on the rolling cadences and thou-shalt-nots of the King James Bible. My name is a birthmark I shall carry to my grave. John Milton and I speak the same language, except that I’m trying to escape it. Like Friedrich Nietzsche, another minister’s son, who went mad in his quest to bury the language of good and evil,[11] I am driven to find the unhandseled realm where language and consciousness were born, before this knowledge was swallowed up by Greek hyperrationalism and the black hole of the Middle Eastern myth of good versus evil.

Nietzsche fascinates me. His fundamental mistake was to use God’s language to write God’s obituary—a case of the serpent swallowing its tail.[12] His philology doomed his agenda from the start.[13] Try as he might, he couldn’t bluster, charm, parse, analyze, or otherwise hammer his way out of the solipsistic narrative that I too was fleeing when I encountered the spirit of Hiawatha, as he too realized that language as he knew it was a death machine.[14]

E. E. Cummings neatly summarizes Nietzsche’s dilemma:

when god decided to invent

everything he took one

breath bigger than a circustent

and everything began

when man determined to destroy

himself he picked the was

of shall and finding only why

smashed it into because[15]

There is truth in the poet’s sly humor. Like the philosophers he railed against (Plato, Aristotle, Fichte, Schelling, Schopenhauer, Hegel, Kant: the man was an equal opportunity hammer),[16] Nietzsche was hopelessly entangled within the last four lines.[17] Only poets escape them. Only poets speak the language of presence: Eros.

Eros knows nothing of good and evil, the juggernaut of death.[18]

In the beginning was not the Word, as the writer of John´s Gospel imagined; in the beginning was this lake in spring rain.[19] That is, in the beginning was Eros (presence), not God, and no man alive or dead can ever write its epitaph. The tension between these two chthonic forces, Eros and God, in Paradise Lost is huge, ambiguous, complex, pornographic, and exhausting—and worth pondering. It took another poet, W. H. Auden, to blow up Milton and the Yahwist author of creation and point us to the far older, authentic, totemic narrative of Eros that is mankind’s natural birthright and proper home:

As long as the apple had not been entirely digested, as long as there remained the least understanding between Adam and the stars, rivers and horses with whom he had once known complete intimacy, as long as Eve could share in any way with the moods of the rose or the ambitions of the swallow, there was still a hope that the effects of the poison would wear off, that the exile from Paradise was only a bad dream, that the Fall had not occurred in fact.[20]

Nietzsche’s steel-trap mind shattered in a spontaneous gesture eerily congruent with Auden’s lines. It happened in Turin, Italy, a town he found specially congenial, especially given his gut ailments.[21] Nietzsche’s landlord, David Fino, was interviewed several years later about the incident.

One day when Mr. Fino was walking along the nearby Via Po—one of the main streets of Turin—he saw a group of people drawing near and in their midst were two municipal guards accompanying “the Professor.” As soon as Nietzsche saw Fino he threw himself into his arms, and Fino easily obtained his release from the guards, who said that they found that foreigner outside the university gates, clinging tightly to the neck of a horse and refusing to let it go.

It was then that the Finos persuaded the professor to take to his bed and sought the assistance of a mental therapist, Professor Turina. But as soon as Nietzsche suspected a doctor was involved, he rebelled, exclaiming, “Pas malade! Pas malade!” The doctor had to be introduced as a family friend before Nietzsche would let himself be treated. . . .

Noticing that Nietzsche [had] sent frequent messages to a certain Professor [Franz] Overbeck, . . . the Fino family thought of telegraphing Overbeck on their own, to inform him of their tenant’s illness. A few days later Overbeck arrived and went up to Nietzsche’s room. It was nightfall and the philosopher was lying in bed. As soon as the two friends saw each other they embraced and wept. Nietzsche wished to get up, sat at the piano and played Wagner.

Two days later, with Overbeck leading him back to his country, Nietzsche left Turin forever, seen off by the Finos, the doctor [Prof. Turina], and the German consul. A while later a letter from the family informed the Finos that Professor Nietzsche had in large part lost his reason and was in a nursing home.[22]

As long as there remained the least understanding between a man and horses with whom he had once known complete intimacy, such a man was capable of going mad.

And he did. As a young man Nietzsche had been an accomplished equestrian in the Prussian artillery. Only an injury kept him from swiftly rising through the ranks. By his own admission, he adored riding (he was a natural) and even found cleaning the stables agreeable.

Language and consciousness, including our sanity, are gifts “woven into us, deep and magical” from the animal beings who have shared in our immense journey.[23] That a philologist and philosopher should seize upon Equus and cling to it in a spectacular gesture of lucidity and, yes, Eros—or was it insanity?—is worth exploring.

“Pas malade! Pas malade!” Nietzsche insisted he was sane. Perhaps he was. Perhaps he had merely passed through the totemic membrane. Wallace Stevens is helpful, here:

The nothingness was a nakedness, a point

Beyond which thought could not progress as thought.

He had to choose. But it was not a choice

Between excluding things. It was not a choice

Between, but of. He chose to include the things

That in each other are included, the whole,

The complicate, the amassing harmony.[24]

Stevens´s amassing harmony is David Bohm´s implicate order, as we shall see.

We will revisit Equus as part of the amassing harmony and implicate order, but first we must encounter the amassing harmony and implicate order of Ursus, the Dark One about whom Eskimos refuse to speak. The one, they whisper, who takes care of them.

________________

Footnotes

[1] Popol Vuh: The Mayan Book of the Dawn of Life, trans. Dennis Tedlock (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1985), 64.

[2] Popol Vuh, 64.

[3] See Kenneth Grahame, The Wind in the Willows (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1933), 126–41.

[4] Psalm 23 (King James Version; henceforth, KJV).

[5] Dante Alighieri, Inferno, trans. Robert and Jean Hollander (New York: Doubleday, 2000), lines 3–9.

[6] Rainer Maria Rilke, “The Man Watching,” in News of the Universe: Poems of Twofold Consciousness, trans. Robert Bly (San Francisco: Sierra Club Books, 1980), 121–22.

[7] Dennis, Cultivating a Landscape of Peace, 102. I have put the speech in the first person singular.

[8] Mary Oliver, “Bone Poem,” in Twelve Moons (Boston: Little, Brown, 1972), 46.

[9] Rainer Maria Rilke, “The Angel,” in New Poems, 1907, trans. Edward Snow (New York: North Point, 1984), 83.

[10] Thoreau, Maine Woods, 94.

[11] ‟You are aware of my demand upon philosophers, that they should take up a stand beyond Good and Evil—that they should have the illusion of the moral judgment beneath them. This demand is the result of a point of view which I was the first to formulate: that there are no such things as moral facts” (Nietzsche, ‟The Improvers of Mankind” in Twilight of the Idols, Section 1).

[12] Friedrich Nietzsche, The Gay Science: With a Prelude in German Rhymes and an Appendix of Songs, ed. Bernard Williams (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 119-120; Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra: A Book for Everyone and No One, trans. R. J. Hollingdale (London, UK: Penguin Books, 1961), 41, 104, 114, 250. ‟God is a too palpably clumsy solution of things; a solution which shows a lack of delicacy towards us thinkers—at bottom He is really no more than a coarse and rude prohibition of us: ye shall not think!” (Nietzsche, Twilight of the Idols, see ‟Why I am so clever.”)

[13] ‟The old God was no longer able to do what he had done formerly. He ought to have been dropped. What happened? The idea of him was changed—the idea of him was denaturalised: this was the price they paid for retaining him.— Jehovah, the God of Justice’, is no longer one with Israel, no longer the expression of a people’s sense of dignity: he is only a god on certain conditions . . . The idea of him becomes a weapon in the hands of priestly agitators who henceforth interpret all happiness as a reward, all unhappiness as a punishment for disobedience to God, for ‘sin’: that most fraudulent method of interpretation which arrives at a so-called ‘moral order of the universe’, by means of which the concept ’cause’ and ‘effect’ is turned upside down” (‟The Antichrist,” pp. 114-115). ‟The concept `God´ was invented as the opposite of the concept of life—everything detrimental, poisonous, and slanderous, and all deadly hostility to life, was bound together in one horrible unit in Him” (Nietzsche, Ecce Homo, p. 260).

[14] ‟It is not the idols of the age but eternal idols which are here struck with a hammer as with a tuning fork.” ‟A Dionysan life-task needs the hardness of the hammer, and one of its first essentials is without doubt the joy even of destruction” (Nietzsche, Twilight of the Idols).

[15] E. E. Cummings, 100 Selected Poems (New York: Grove Press, 1923), 93.

[16] See Nietzsche, ‟The Hammer Speaketh,” Twilight of the Idols, p. 89. See also p. 171 in Ecce Homo.

[17] In the end, Nietzsche appeals to science. ‟Science storms heaven itself, it rings the death-knell of the gods” Nietzsche, ‟The Antichrist,” p. 142. From science is born the Superman.

[18] In fairness to him, Nietzsche, in his critique of good and evil, approached this realization with his wild enthusiasm for Dionysian orgies, but certainly didn´t see it the way I am describing it here. See ‟Twilight of the Idols,” pp. 86-88. See also, of course, Beyond Good and Evil. ‟Christianity gave Eros poison to drink; he did not die of it, certainly, but degenerated to Vice” (Beyond Good and Evil p. 94).

[19] John 1:1 (KJV).

[20] Auden, “For the Time Being,” 247.

[21] ‟Here in Turin… every face brightens and softens at the sight of me. A thing that has flattered me more than anything else hitherto, is the fact that old market-women cannot rest until they have picked out the sweetest of their grapes for me” (Twilight of the Idols, p. 207).

[22] Anacleto Verrecchia, “Nietzsche’s Breakdown in Turin,” in Nietzsche in Italy, ed. Thomas Harrison (Saratoga, CA: ANMA Libri, 1988), 105–6.

[23] Rilke, “The Singer Sings before a Child of Princes,” in The Book of Images, trans. Edward Snow (New York: North Point, 1991), 169.

For the role of animals in shaping our consciousness, our mind, I recommend the work of the late philosopher and zoologist, Paul Shepard, especially Thinking Animals: Animals and the Development of Human Intelligence. New York: The Viking Press, 1978; and The Others: How Animals Made Us Human. Washington, D. C.: Island Press/Shearwater Books, 1996.

[24] Stevens, “It Must Give Pleasure,” in Selected Poems, 124.